- About

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Education.

Prioritize knowledge. Make better choices.

- Evidence.

Sort good studies from the bad.

- Regrowth.

Get bigger hair gains.

Team MembersPhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Rob English

Founder, researcher, & consumer advocate

- Research Team

Our team of PhD’s, researchers, & more

Editorial PolicyDiscover how we conduct our research.

ContactHave questions? Contact us.

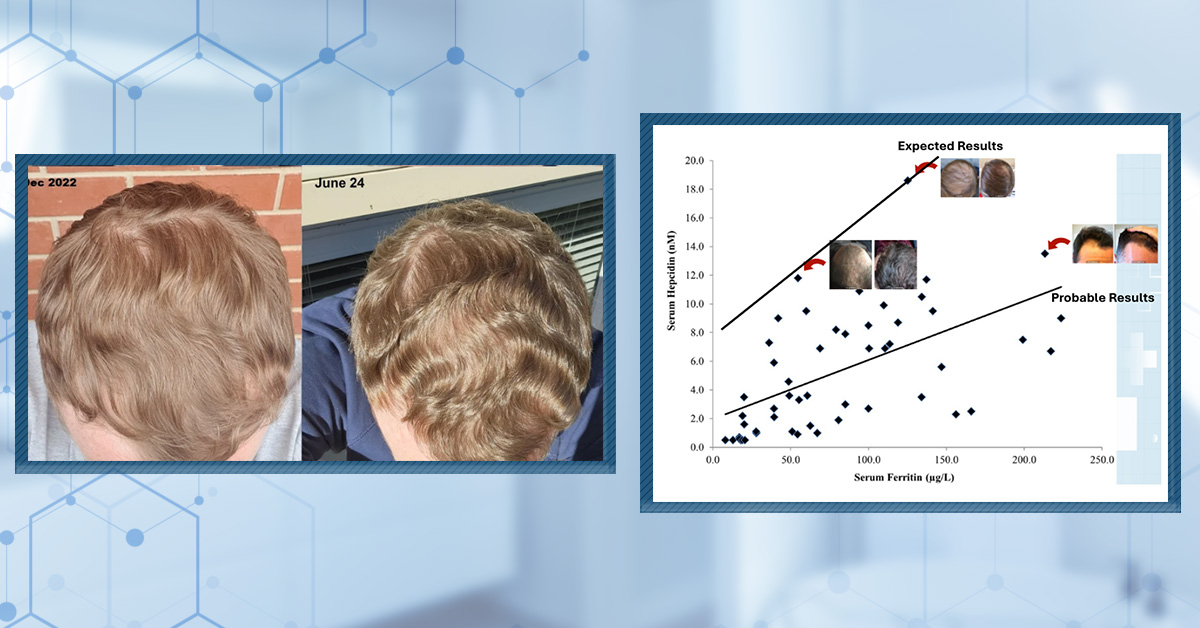

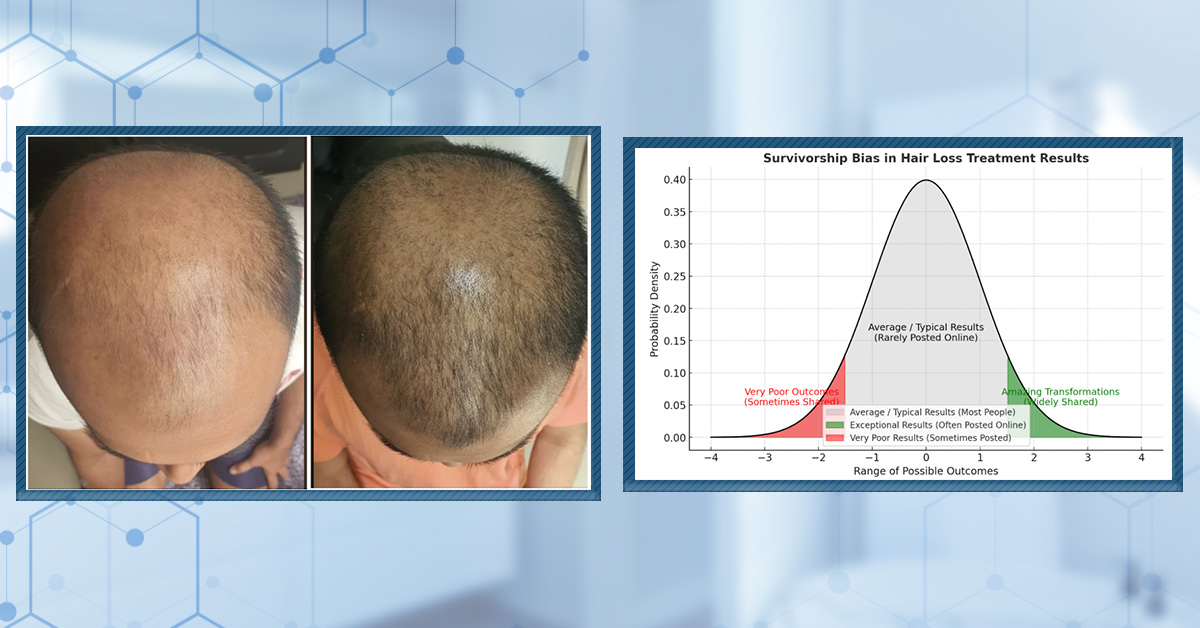

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- — Jenna, 31, U.S.A.

I have attached my before and afters of my progress since joining this group...

- — Tom, 30, U.K.

I’m convinced I’ve recovered to probably the hairline I had 3 years ago. Super stoked…

- — Rabih, 30’s, U.S.A.

My friends actually told me, “Your hairline improved. Your hair looks thicker...

- — RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A.

I also feel my hair has a different texture to it now…

- — Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA

Firstly thank you for your work in this field. I am immensely grateful that...

- — Ben M., U.S.A

I just wanted to thank you for all your research, for introducing me to this method...

- — Raul, 50, Spain

To be honest I am having fun with all this and I still don’t know how much...

- — Lisa, 52, U.S.

I see a massive amount of regrowth that is all less than about 8 cm long...

Client Testimonials150+ member experiences.

Scroll Down

Popular Treatments- Treatments

Popular treatments. But do they work?

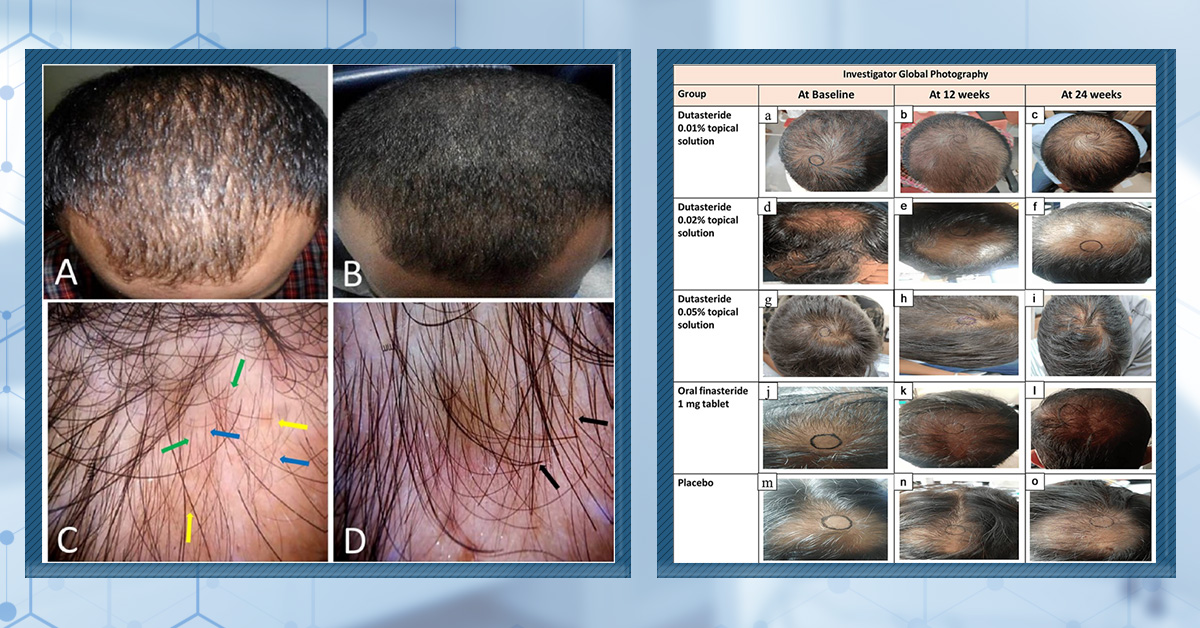

- Finasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Dutasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Mesotherapy

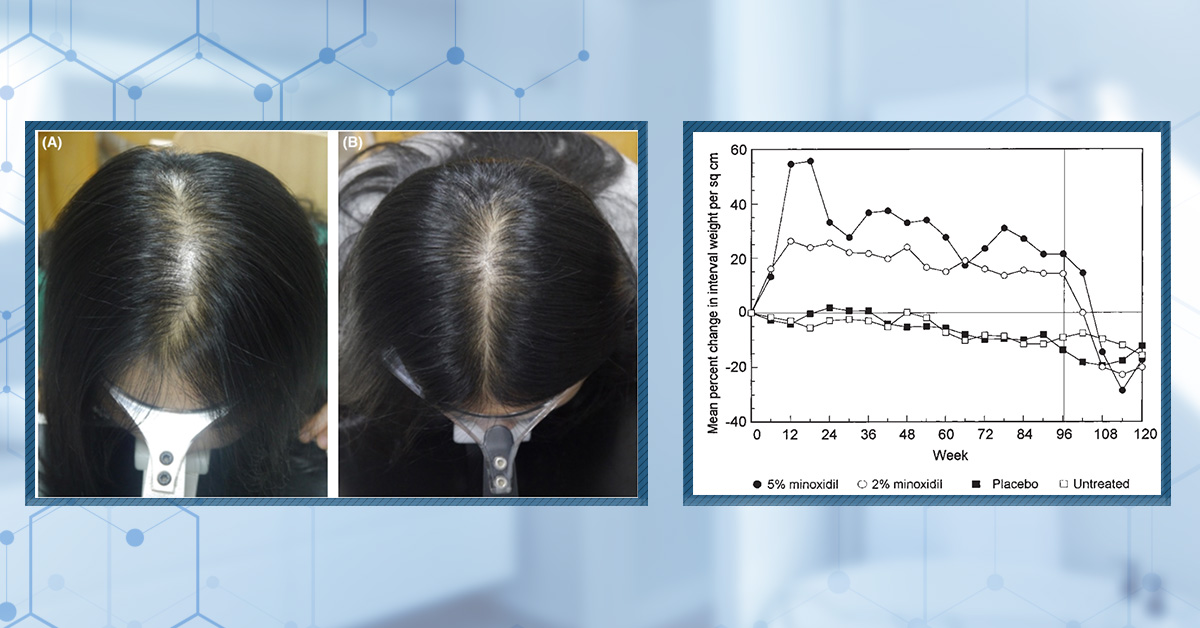

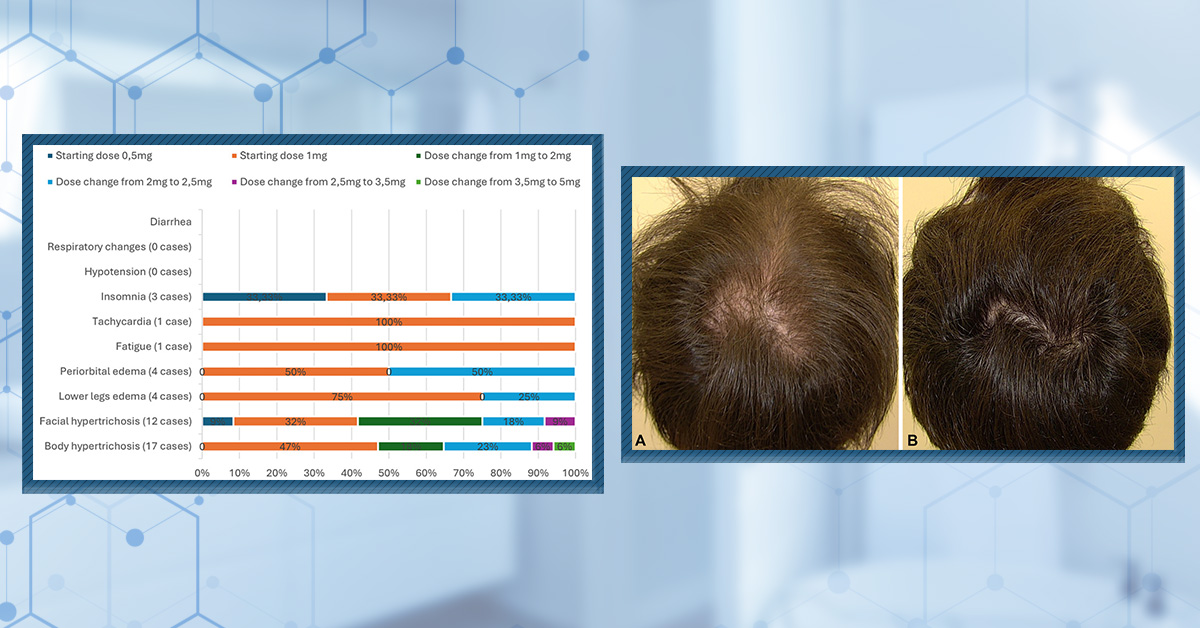

- Minoxidil

- Oral

- Topical

- Ketoconazole

- Shampoo

- Topical

- Low-Level Laser Therapy

- Therapy

- Microneedling

- Therapy

- Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy (PRP)

- Therapy

- Scalp Massages

- Therapy

More

IngredientsTop-selling ingredients, quantified.

- Saw Palmetto

- Redensyl

- Melatonin

- Caffeine

- Biotin

- Rosemary Oil

- Lilac Stem Cells

- Hydrolyzed Wheat Protein

- Sodium Lauryl Sulfate

More

ProductsThe truth about hair loss "best sellers".

- Minoxidil Tablets

Xyon Health

- Finasteride

Strut Health

- Hair Growth Supplements

Happy Head

- REVITA Tablets for Hair Growth Support

DS Laboratories

- FoliGROWTH Ultimate Hair Neutraceutical

Advanced Trichology

- Enhance Hair Density Serum

Fully Vital

- Topical Finasteride and Minoxidil

Xyon Health

- HairOmega Foaming Hair Growth Serum

DrFormulas

- Bio-Cleansing Shampoo

Revivogen MD

more

Key MetricsStandardized rubrics to evaluate all treatments.

- Evidence Quality

Is this treatment well studied?

- Regrowth Potential

How much regrowth can you expect?

- Long-Term Viability

Is this treatment safe & sustainable?

Free Research- Free Resources

Apps, tools, guides, freebies, & more.

- Free CalculatorTopical Finasteride Calculator

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: What Causes Hair Loss?

- Free ResourceFree Guide: Standardized Scalp Massages

- Free Course7-Day Hair Loss Email Course

- Free DatabaseIngredients Database

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: Hair Loss Disorders

- Free DatabaseTreatment Guides

- Free Lab TestsProduct Lab Tests: Purity & Potency

- Free Video & Write-upEvidence Quality Masterclass

- Free Interactive GuideDermatology Appointment Guide

More

Articles100+ free articles.

-

Hims Hair Growth Reviews: The Pros, Cons, and Real Results

-

Topical Finasteride Before and After: Real Case Studies

-

How to Reduce the Risk of Finasteride Side Effects

-

10 Best DHT-Blocking Shampoos

-

Best Minoxidil for Men: Top Picks for 2026

-

7 Best Oils for Hair Growth

-

Switching From Finasteride to Dutasteride

-

Best Minoxidil for Women: Top 6 Brands of 2026

PublicationsOur team’s peer-reviewed studies.

- Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review

- Use of Botulinum Toxin for Androgenic Alopecia: A Systematic Review

- Conflicting Reports Regarding the Histopathological Features of Androgenic Alopecia

- Self-Assessments of Standardized Scalp Massages for Androgenic Alopecia: Survey Results

- A Hypothetical Pathogenesis Model For Androgenic Alopecia:Clarifying The Dihydrotestosterone Paradox And Rate-Limiting Recovery Factors

Menu- AboutAbout

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Team Members

PhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Editorial Policy

Discover how we conduct our research.

- Contact

Have questions? Contact us.

- Before-Afters

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- Client Testimonials

Read the experiences of members

Before-Afters/ Client Testimonials- Popular Treatments

-

Articles

Progesterone is a steroid hormone with a wide range of physiological and medical effects. It is linked to female fertility and pregnancy, and it plays roles in neuro- and immunoprotection and various gynecological treatments. Studies have linked changes in progesterone levels to androgenic alopecia and postpartum telogen effluvium. Still, mixed evidence, limited research, and potential side effects have led to this treatment not being widely adopted.

In this article, we will explore the association between progesterone and hair loss, particularly female pattern hair loss (FPHL), and determine whether supplementation with progesterone can improve hair loss outcomes.

Key Takeaways

- What Is It? Progesterone is a steroid hormone that is essential for a wide range of physiological processes. Deficiencies are associated with menstrual irregularities, fertility and pregnancy issues, mood and sleep disturbance, and physical symptoms. Other signs can include dry skin and thinning hair.

- Evidence Quality: The evidence quality is 31/100 based on our metrics.

- Clinical Data: There is very limited evidence supporting using progesterone to improve hair loss outcomes.

- Study 1: 10 male patients with AGA were treated with a lotion containing 11a-hydroxyprogesterone. Improvements were observed in the “cranial” region of the scalp but not the left temporal region.

- Study 2: 6 male patients with AGA were treated with 100 mg of progesterone for 6 months. Improvements were observed in new hair growth and the transition from vellus to terminal hairs.

- Dosing & Formulation Considerations: Know your progestins! Many synthetic progesterone formulations are actually androgenic in nature rather than anti-androgenic. While some have more recently been developed to behave more closely to natural progesterone, there is data lacking in their efficacy to improve hair regrowth. We recommend sticking with natural progesterone until further research is available. If you are using natural progesterone, micronized allows for better systemic absorption especially when taken orally. It is typically prescribed at 200 mg daily for 12 days per 28-day cycle. However, it has not been tested for hair loss. If you decide to use non-micronized progesterone, a topical formulation may be more beneficial as oral is heavily metabolized and, therefore, may not reach the strength needed to affect hair growth outcomes. If you decide to take synthetic progestins, you might find results with cyproterone acetate or drospirenone (Slynd); however, once again, data is limited.

All-Natural Hair Supplement + Topical

The top natural ingredients for hair growth, all in one serum & supplement.

Take the next step in your hair growth journey with a world-class natural serum & supplement. Ingredients, doses, & concentrations built by science.

What Is Progesterone?

Progesterone is an important steroid hormone that plays several key roles in the female reproductive system. It is primarily produced by the corpus luteum in the ovaries after ovulation in women. For men, progesterone is produced in smaller amounts by the adrenal glands and is associated with sperm development.[1]Nio-Kobayashi, J., Miyazaki, K., Hashiba, K., Okuda, K., Iwanaga, T. (2016). Histological analysis of arteriovenous anastomosis-like vessels established in the corpus luteum of cows during … Continue reading,[2]Mirihagelle, S., Hughes, J.R., Miller, D.J. (2022). Progesterone-induced sperm release from the oviduct sperm reservoir. Cells. 11(10). 1622. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11101622

Figure 1. Progesterone molecule.

The association between progesterone and hair health is multifaceted, involving direct hormonal effects and indirect influences.

Studies have shown that progesterone, due to its 5-alpha-reductase (5-AR) inhibiting properties, can help balance the potentially negative effects of androgens like testosterone. When progesterone levels decline, increased conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone by 5-AR can occur, leading to hair follicle miniaturization and hair thinning.[3]Grymowicz, M., Rudnicka, E., Podfigurna, A., Napierała, P., Smolarczyk, R., Smolarczyk, K., Męczekalski, B. (2020). Hormonal effects on hair follicles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. … Continue reading

Significant hormonal changes occur in menopausal women, including a decrease in estrogen and progesterone levels. Estrogen prolongs the growing (anagen) phase of the hair follicle cycle, and progesterone indirectly supports this through its androgen-inhibiting activity. Therefore, a reduction in both estrogen and progesterone can leave menopausal women vulnerable to increased androgen levels and subsequent hair loss.

Changes in progesterone levels can also affect postpartum women. During pregnancy, progesterone levels are significantly elevated but drop sharply after childbirth. This sudden decrease in progesterone and estrogen is believed to contribute to postpartum telogen effluvium (PPTE). However, unlike the other examples mentioned above, PPTE is generally self-limiting. It occurs 2-4 months after delivery and resolves typically within 6-24 weeks (although in rare cases, it can persist up to 15 months).[4]Cleveland Clinic. (no date). Postpartum Hair Loss. Cleveland Clinic. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23297-postpartum-hair-loss (Accessed: September 2024)

So, we know how progesterone deficits might lead to hair loss, but does progesterone supplementation improve hair loss outcomes?

Can Progesterone Improve Hair Loss Outcomes?

As previously mentioned, progesterone has some 5-AR inhibitory properties. However, there is limited evidence to show that it can improve hair loss outcomes.

One 1987 study treated ten male patients with AGA with a lotion containing 1% 11a-hydroxyprogesterone (a progesterone derivative) for one year, and 8 patients were treated with a control.[5]Van der Willigen, A.H., Peereboom-Wynia, J.D.R., van Joost, TH., Stolz, E. (1987). A preliminary study of the effect of 11a hydroxyprogesterone on hair growth in men suffering from androgenetic … Continue reading Those treated with the progesterone derivative showed an increase in the number of anagen hairs (45 to 51) and mean hair shaft diameter (69.6 μm to 71.6 μm) in the “cranial” region of the scalp. Further improvements were seen with reduced regressing/non-growing (catagen/telogen) hairs (46-40). Unfortunately, without images, we can’t see if these improvements led to a clinically significant outcome.

Furthermore, the study also analyzed hair counts on the left temporal side of the scalp. Here, the number of anagen hairs reduced from 67 to 62, and the number of catagen/telogen hairs increased from 21 to 30, indicating a varied response to the treatment.

Figure 2: Hair counts after topical application of a progesterone derivative.[6]Van der Willigen, A.H., Peereboom-Wynia, J.D.R., van Joost, TH., Stolz, E. (1987). A preliminary study of the effect of 11a hydroxyprogesterone on hair growth in men suffering from androgenetic … Continue reading

Another small study was conducted with 6 males with AGA, acne, and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).[7]Kalinchenko, S., Nikiforov, I., Samburskaya, O. (2022). BPH, Androgenic Alopecia, and Acne – Markers of Progesterone Deficiency. Journal of the Endocrine Society. 6. 431-432. Available at: … Continue reading The participants were treated with Vitamin D and 100 mg progesterone daily for 6 months. After this period, the authors reported that the patients had reduced hair loss, new hair growth, and increased vellus transition to terminal hairs. Unfortunately, the authors didn’t report the specific values or show any photos. Furthermore, it is not possible to know if the positive effects were due to supplementing with Vitamin D.

While there is a logical reasoning behind the use of progesterone for women undergoing menopause suffering from female pattern hair loss, there is no clinical evidence demonstrating its efficacy.

Progesterone Formulations

There are a number of formulations of progesterone, but how effective might they be at improving hair loss outcomes?

Oral

Oral progesterone is typically prescribed for hormone replacement therapy (HRT). However, due to its metabolism, oral progesterone may only have limited benefits for hair loss. It undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism in the liver, leading to significant degradation of the hormone before it reaches the systemic circulation, meaning that limited amounts of the hormone may reach the scalp.[8]Coombes, Z., Plant, K., Freire, C., Basit, A.W., Butler, P., Conlan, R.S., Gonzalez, D. (2021). Progesterone metabolism by human and rat hepatic and intestinal tissue. Pharmaceutics. 13(10). 1707. … Continue reading

Topical

Topical progesterone has a few potential benefits, including:

- Localized application

- Fewer systemic side effects

- Bypass first pass metabolism, so more is reaching the target area

According to one source, the most common strength of progesterone applied topically is around 2%. However, this appears to be based on clinical experience rather than published studies.[9]Roseway Labs. (2020). Topicals for Hair Loss. Roseway Labs. Available at: https://rosewaylabs.com/topicals-for-hair-loss/ (Accessed: September 2024)

Injection

While some clinics use injected progesterone combined with other treatments, like platelet-rich plasma (you can find videos of these if you search on YouTube) to treat hair thinning, there is no peer-reviewed, published clinical evidence to suggest that it improves hair loss outcomes.

Micronized

Recently, there has been interest in using micronized progesterone and its potential as a hair growth treatment. This formulation may offer improved absorption and efficacy in balancing hormone levels, potentially aiding hair growth.

Micronized progesterone is a formulation of progesterone that has been processed to create very small particles smaller than 10 μm in size. This process increases the surface area of progesterone particles, allowing for better systemic absorption, especially when taken orally.[10]Hargrove, J.T., Maxson, W.S., Wentz, A.C. (1989). Absorption of oral progesterone is influenced by vehicle and particle size. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 161(4). 948-951. Available … Continue reading

Micronized progesterone is chemically identical to the progesterone that is naturally produced in the human body, meaning it should work similarly.[11]de Lignieres, B. (1999). Oral micronized progesterone. Clinical Therapeutics. 21(1). 41-60. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2917(00)88267-3 It is currently used as an HRT for menopausal symptoms, to support pregnancy and fertility, and to treat gynecological disorders.[12]Memi, E., Pavli, P., Papagianni, M., Vrachnis, N., Mastorakos, G. (2024). Diagnostic and therapeutic use of oral micronized progesterone in endocrinology. Reviews in endocrine and metabolic … Continue reading

While we have recently been getting a lot of emails from members about micronized progesterone, there is a significant gap in the literature about its potential efficacy in treating hair loss in menopausal women or people with AGA.

Synthetic Progesterone

We have discussed natural progesterone in-depth, so let’s also examine synthetic progesterone (progestins) and how it differs from natural progesterone.

Progestins differ from natural progesterone in their chemical structure, which results in different physiological effects. Some common synthetic progestins include norethindrone, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), norethisterone (NET-A), and levonorgestrel. Unlike natural progesterone, many synthetic progestins can increase androgen activity. This is critical to keep in mind when choosing whether to take progestins if you suffer from hair loss. Furthermore, progestins can cause other unwanted side effects like acne, excessive hair growth in unwanted areas, and changes in skin texture, alongside more serious increased risks such as cardiovascular events (heart attacks and strokes) and cancers.

One study published in 2017 examined the androgenic and estrogenic properties of various progestins, including MPA and NET-A. The findings indicated that these progestins bind to the androgen receptor (AR) with affinities comparable to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), suggesting that they can exert androgenic effects in vivo (in cells).[13]Louw-du Toit, R., Perkins, M.S., Hapgood, J.P., Africander, D. (2017). Comparing the androgenic and estrogenic properties of progestins used in contraception and hormone therapy. Biochemical and … Continue reading

Research on hormonal contraceptives highlighted that synthetic progestins can lead to hair loss. One review conducted on data on alopecia associated with the levonorgestrel IUD found a number of women who had the IUD implanted between 2000-2001 experienced hair loss. Furthermore, in some of these cases, when the IUD was removed, women recovered their hair loss, indicating a direct effect of levonorgestrel on hair loss for some people. Unfortunately, this study is limited in many ways, including being a retrospective study and only having 73 total reports of alopecia (in New Zealand and using World Health Organization data).[14]Paterson, H., Clifton, J., Miller, D., Ashton, J., Harrison-Woolrych, M. (2007(. Hair loss with use of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device. Contraception 76. 306-309. Available at: … Continue reading

A case study from 2002, this time conducted on a woman taking a combination low-dose oral contraceptive (norethindrone and ethinyl estradiol), found shortly after starting, she experienced hair loss, which abated when stopped.[15]Yokoyama, Y., Sato, S., Saito, Y. (2002). Alopecia related to low-dose oral contraceptives. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 47. 266-246. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/pl00007489

So, it seems like if you have AGA, you might want to avoid synthetic progestins. But are there exceptions to the rule? There might be.

Cyproterone Acetate

While cyproterone acetate is a progestin, it has shown potential in improving hair regrowth in women with androgenic alopecia. In a study involving 80 women with FPHL treated with either 200 mg spironolactone, 50 mg of cyproterone acetate, or 100 mg daily for 10 days per month if menopausal, 44% of those treated with cyproterone acetate experienced hair regrowth. However, another 44% saw no change, and 12% continued to lose hair. There was also no significant difference between the cyproterone acetate and spironolactone groups.[16]Sinclair, R., Wewerinke, M., Jolley, D. (2005). Treatment of female pattern hair loss with oral antiandrogens. British Journal of Dermatology. 152(3). 466-473. Available at: … Continue reading

Another study reported that 77.1% of 35 women with androgenic alopecia observed hair regrowth after three months of treatment with the combined cyproterone acetate and ethinyl estradiol pill (2mg). 42.8% of participants had slight regrowth, 34.3% had moderate regrowth after trichoscopic assessment, and 22.8% showed no regrowth at all.[17]Coneac, A., Muresan, A., Orasan, M.S. (2014). Antiandrogenic therapy with ciproterone acetate in female patients who suffer from both androgenic alopecia and acne vulgaris. Clujul Medical. 87(4). … Continue reading

Figure 3. Effect of cyproterone acetate on hair regrowth. [18]Coneac, A., Muresan, A., Orasan, M.S. (2014). Antiandrogenic therapy with ciproterone acetate in female patients who suffer from both androgenic alopecia and acne vulgaris. Clujul Medical. 87(4). … Continue reading

A 12-month randomized trial found that cyproterone acetate was more effective than minoxidil at treating hair loss in women with signs of hyperandrogenism, which may be worth considering when considering hair loss treatments.[19]Vexiau, P., Chaspoux, C., Boudou, P., Fiet, J., Jouanique, C., Hardy, N., Reygagne, P. (2002). Effects of minoxidil 2% vs. cyproterone acetate treatment on female androgenetic alopecia: a controlled, … Continue reading

Drospirenone

Drospirenone (also known under the brand name Slynd) is a newer synthetic progesterone that has a unique profile. It is derived from spironolactone, a drug you may be familiar with, as it also has anti-androgenic properties. Like cyproterone acetate, Slynd does not increase androgenic activity. Instead, it has androgenic properties similar to natural progesterone, which makes it an attractive potential treatment.[20]Regidor, P.A., Mueller, A., Mayr, M. (2023). Pharmacological and metabolic effects of drospirenone as a progestin-only pill compared to combined formulations with estrogen. Womens Health (Lond). 19. … Continue reading

However, the data on hair loss is limited. One study evaluated the efficacy of oral finasteride therapy combined with an oral contraceptive containing drosperinone and ethinyl estradiol in premenopausal women with FPHL. The study found that 62% of patients showed some improvement in hair loss, but it was unclear whether the improvement was due to the higher dosage of finasteride or the combination with the oral contraceptive.[21]Iorizzo, M., Vincenzi, C., Voudouris, S., Piraccini, B.M., Tosti, A. (2006). Finasteride treatment of female pattern hair loss. Archives of Dermatology. 142(3). 298-302. Available at: … Continue reading

Furthermore, if you are sensitive or respond poorly to spironolactone, you might also experience side effects with Slynd. Another factor is that as a synthetic progestin, it might also carry elevated cardiovascular and cancer risks.

Other “new” progestins have also been developed and designed to be closer in mechanism of action to progesterone than other synthetics. These are dienogest, nestorone, nomegestrol acetate, and trimegestone, which have anti-androgenic activity, that may benefit those with hair loss, but again, they haven’t been tested.[22]Sitruk-Ware, R. (2006). New progestagens for contraceptive use. Human Reproduction Update. 12(2). 169-178. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmi046

Dosing Considerations

Oral micronized progesterone is typically prescribed at 200 mg daily for 12 days per 28-day cycle for postmenopausal women or 400 mg daily for 10 days for women who have not had a period for at least three consecutive months.[23]Memi, E., Pavli, P., Papagianni, M., Vrachnis, N., Mastorakos, G. (2024). Diagnostic and therapeutic use of oral micronized progesterone in endocrinology. Reviews in endocrine and metabolic … Continue reading It may be beneficial for women with female pattern hair loss.

Topical progesterone creams are often used in doses ranging from 20 to 40 mg, applied once or twice daily. For example, one study conducted with post-menopausal women used 40 mg daily or 20 mg twice daily for 42 days.[24]Carey, B.J., Carey, A.H., Patel, S., Carter, G., Studd, J.W. (2000). A study to evaluate serum and urinary hormone levels following short and long term administration of two regimens of progesterone … Continue reading

Injectable progesterone is injected primarily at around 150 mg every 12 weeks.[25]Nelson, A., (2002). Merits of DMPA relative to other reversible contraceptive methods. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 47(9). 781-784. PMID: 12380406

Based on the research above, the dose for cyproterone acetate is around 50 – 100 mg, but this was given with ethinyl estradiol. For Slynd, the standard contraceptive dose of 4 mg orally once daily for 24 days followed by 4 inactive days may have potential benefits.

Dosing should be individualized based on the patient’s age, health status, and specific hormonal imbalances. Patients should report any concerning side effects to their doctor straight away. Close monitoring and adjustment of dosage by a healthcare provider are important, as effects can vary between individuals.

Best Practices

- Premenopausal Women: Progesterone supplementation may be used to address hormonal imbalances contributing to hair thinning.

- Postmenopausal Women: HRT with progesterone is more common, particularly in combination with estrogen, to combat hair loss linked to reduced hormone levels during menopause.

- Individuals with Androgenic Hair Loss: Progesterone as an adjunct to other anti-androgen therapies (e.g., spironolactone) for hair loss management (if you are pre-menopausal).[26]Brough, K.R., Torgerson, R.R. (2017). Hormonal therapy in female pattern hair loss. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. 3. 53-57. Available at: … Continue reading

- Key Considerations: Before starting progesterone therapy, it is important to undergo individualized hormone testing and consult with a healthcare provider. Monitor for side effects such as mood changes, weight gain, or changes in menstrual patterns

Ultimately, due to the lack of evidence, we believe that steering clear of synthetic progestins, for the most part, would be best until newer data comes out supporting their use in hair growth. As it stands there may be some promising candidates, but its clear from our research that there is a gap in the evidence.

Final Thoughts

While progesterone, particularly in topical and micronized formulations, may benefit women suffering from FPHL or other hormonally influenced hair loss, more high-quality research is needed. If you are thinking about using progesterone, consult with your doctor or healthcare professional to ensure that it is tailored to your needs.

References[+]

References ↑1 Nio-Kobayashi, J., Miyazaki, K., Hashiba, K., Okuda, K., Iwanaga, T. (2016). Histological analysis of arteriovenous anastomosis-like vessels established in the corpus luteum of cows during luteolysis. Journal of Ovarian Research. 9(67). 1-14. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-016-0277-0 ↑2 Mirihagelle, S., Hughes, J.R., Miller, D.J. (2022). Progesterone-induced sperm release from the oviduct sperm reservoir. Cells. 11(10). 1622. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11101622 ↑3 Grymowicz, M., Rudnicka, E., Podfigurna, A., Napierała, P., Smolarczyk, R., Smolarczyk, K., Męczekalski, B. (2020). Hormonal effects on hair follicles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21(15). 5342. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21155342 ↑4 Cleveland Clinic. (no date). Postpartum Hair Loss. Cleveland Clinic. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23297-postpartum-hair-loss (Accessed: September 2024) ↑5, ↑6 Van der Willigen, A.H., Peereboom-Wynia, J.D.R., van Joost, TH., Stolz, E. (1987). A preliminary study of the effect of 11a hydroxyprogesterone on hair growth in men suffering from androgenetic alopecia. Acta dermato-venereologica. 67(1). 82-85. PMID: 2436423 ↑7 Kalinchenko, S., Nikiforov, I., Samburskaya, O. (2022). BPH, Androgenic Alopecia, and Acne – Markers of Progesterone Deficiency. Journal of the Endocrine Society. 6. 431-432. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvac150 ↑8 Coombes, Z., Plant, K., Freire, C., Basit, A.W., Butler, P., Conlan, R.S., Gonzalez, D. (2021). Progesterone metabolism by human and rat hepatic and intestinal tissue. Pharmaceutics. 13(10). 1707. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics13101707 ↑9 Roseway Labs. (2020). Topicals for Hair Loss. Roseway Labs. Available at: https://rosewaylabs.com/topicals-for-hair-loss/ (Accessed: September 2024) ↑10 Hargrove, J.T., Maxson, W.S., Wentz, A.C. (1989). Absorption of oral progesterone is influenced by vehicle and particle size. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 161(4). 948-951. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(89)90759-x ↑11 de Lignieres, B. (1999). Oral micronized progesterone. Clinical Therapeutics. 21(1). 41-60. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2917(00)88267-3 ↑12, ↑23 Memi, E., Pavli, P., Papagianni, M., Vrachnis, N., Mastorakos, G. (2024). Diagnostic and therapeutic use of oral micronized progesterone in endocrinology. Reviews in endocrine and metabolic disorders. 25(4). 751-772. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-024-09882-0 ↑13 Louw-du Toit, R., Perkins, M.S., Hapgood, J.P., Africander, D. (2017). Comparing the androgenic and estrogenic properties of progestins used in contraception and hormone therapy. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. (491)1. 140-146. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.07.063 ↑14 Paterson, H., Clifton, J., Miller, D., Ashton, J., Harrison-Woolrych, M. (2007(. Hair loss with use of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device. Contraception 76. 306-309. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2007.06.015 ↑15 Yokoyama, Y., Sato, S., Saito, Y. (2002). Alopecia related to low-dose oral contraceptives. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 47. 266-246. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/pl00007489 ↑16 Sinclair, R., Wewerinke, M., Jolley, D. (2005). Treatment of female pattern hair loss with oral antiandrogens. British Journal of Dermatology. 152(3). 466-473. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06218.x ↑17 Coneac, A., Muresan, A., Orasan, M.S. (2014). Antiandrogenic therapy with ciproterone acetate in female patients who suffer from both androgenic alopecia and acne vulgaris. Clujul Medical. 87(4). 226-234. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15386/cjmed-386 ↑18 Coneac, A., Muresan, A., Orasan, M.S. (2014). Antiandrogenic therapy with ciproterone acetate in female patients who suffer from both androgenic alopecia and acne vulgaris. Clujul Medical. 87(4). 226-234. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15386/cjmed-386 ↑19 Vexiau, P., Chaspoux, C., Boudou, P., Fiet, J., Jouanique, C., Hardy, N., Reygagne, P. (2002). Effects of minoxidil 2% vs. cyproterone acetate treatment on female androgenetic alopecia: a controlled, 12-month randomized trial. British Journal of Dermatology. 146(6). 992-999. Available at: https//doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04798.x ↑20 Regidor, P.A., Mueller, A., Mayr, M. (2023). Pharmacological and metabolic effects of drospirenone as a progestin-only pill compared to combined formulations with estrogen. Womens Health (Lond). 19. 1-10. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/17455057221147388 ↑21 Iorizzo, M., Vincenzi, C., Voudouris, S., Piraccini, B.M., Tosti, A. (2006). Finasteride treatment of female pattern hair loss. Archives of Dermatology. 142(3). 298-302. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1001/archderm.142.3.298 ↑22 Sitruk-Ware, R. (2006). New progestagens for contraceptive use. Human Reproduction Update. 12(2). 169-178. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmi046 ↑24 Carey, B.J., Carey, A.H., Patel, S., Carter, G., Studd, J.W. (2000). A study to evaluate serum and urinary hormone levels following short and long term administration of two regimens of progesterone creams in postmenopausal women. BJOG. 107(6). 722-726. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13331.x ↑25 Nelson, A., (2002). Merits of DMPA relative to other reversible contraceptive methods. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 47(9). 781-784. PMID: 12380406 ↑26 Brough, K.R., Torgerson, R.R. (2017). Hormonal therapy in female pattern hair loss. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. 3. 53-57. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.01.001 CRABP2 is one of two genes found within the CRABP family alongside CRABP1. CRABP2 is a key regulator of retinoic acid, a vitamin A derivative, transporting it around the cell and helping its metabolism. Both CRABP2 and retinoic acid have been suggested in the literature to have roles in the maintenance of hair health. This is particularly evident for retinoic acid, which has been suggested to regulate hair health in a dose-dependent manner. A few studies have also investigated genetic variation in CRABP2, suggesting that some variants may be linked to hair loss. This article will explore how relevant CRABP2 is to hair loss treatment effectiveness and how to interpret your genetic results to make the correct treatment choice.

Interested in Topical Minoxidil?

High-strength topical minoxidil available, if prescribed*

Take the next step in your hair regrowth journey. Get started today with a provider who can prescribe a topical solution tailored for you.

*Only available in the U.S. Prescriptions not guaranteed. Restrictions apply. Off-label products are not endorsed by the FDA.

What is CRABP2?

The cellular retinoic acid binding protein (CRABP) gene family is very small, consisting of just two members – cellular retinoic acid binding protein 1 (CRABP1) and cellular retinoic acid binding protein 2 (CRABP2). CRABP1 is expressed throughout the body, whereas CRABP2 expression is restricted to certain tissues, such as the skin. Both CRABP genes are high-affinity binding proteins of retinoic acid, which is a derivative of vitamin A. Although research has yet to fully elucidate their exact functions, it is understood that CRABP1 and CRABP2 both play a role in the transport and metabolism of retinoic acid.[1]Wei, L. N. (2016). Cellular retinoic acid binding proteins: Genomic and non-genomic functions and their regulation. The Biochemistry of Retinoid Signaling II: The Physiology of Vitamin A-Uptake, … Continue reading

In sheep, it has been shown that CRABP2 is highly expressed in dermal papilla cells (DPCs), which play a key role in the growth and development of hair follicles. Moreover, they showed that CRABP2 regulates the proliferation of DPCs and that the overexpression of CRABP2 promoted increased DPC proliferation. Although this research was conducted in cells taken from sheep, it does suggest that CRABP2 may play a role in the maintenance of hair.[2]He, M., Lv, X., Cao, X., Yuan, Z., Quan, K., Getachew, T., Mwacharo, J.M., Haile, A., Li, Y., Wang, S. and Sun, W. (2023). CRABP2 Promotes the Proliferation of Dermal Papilla Cells via the … Continue reading

These results suggest that increased expression of CRABP2 could be beneficial for hair loss. However, the association between CRABP2 and hair maintenance is slightly more complex than it first appears. In tissue taken from a mouse model of alopecia areata (AA), the expression of CRABP2 (both the gene and protein) was increased compared to control mice. Similarly, CRABP2 protein expression was higher in tissue taken from humans with AA. Ultimately, the findings of the paper suggest that increased retinoic acid synthesis may contribute to the pathogenesis of AA.[3]Duncan, F.J., Silva, K.A., Johnson, C.J., King, B.L., Szatkiewicz, J.P., Kamdar, S.P., Ong, D.E., Napoli, J.L., Wang, J., King Jr, L.E. and Whiting, D.A. (2013). Endogenous retinoids in the … Continue reading

Conversely, it has also been shown that a reduction in retinoic acid signaling may be associated with hair loss. Mice lacking a key retinoic acid receptor exhibited impaired anagen initiation within their hair follicles (the growing phase), which was likely a contributory factor in the progressive alopecia that these mice developed.[4]Li, M., Chiba, H., Warot, X., Messaddeq, N., Gérard, C., Chambon, P., & Metzger, D. (2001). RXRα ablation in skin keratinocytes results in alopecia and epidermal alterations. Development, … Continue reading

Further evidence has been added to support these findings, suggesting that retinoic acid signaling may contribute to AGA similarly to androgens. It is widely accepted that androgens drive the pathogenesis of AGA and lead to the miniaturization of hair follicles. However, a study conducted in 30 male patients with AGA revealed that genes involved in retinoic acid signaling are upregulated, suggesting that retinoic acid signaling may promote follicle miniaturization.[5]Ho, B.S.Y., Vaz, C., Ramasamy, S., Chew, E.G.Y., Mohamed, J.S., Jaffar, H., Hillmer, A., Tanavde, V., Bigliardi-Qi, M. and Bigliardi, P.L. (2019). Progressive expression of PPARGC1α is associated … Continue reading

Despite appearing contradictory, it is possible that all of these studies are accurate and that both a deficiency and excess of retinoic acid can contribute to hair loss. Indeed, the literature suggests that retinoic acid may regulate hair health in a dose-dependent manner, whereby the optimal and ‘healthy’ level of retinoic acid sits somewhere between low and high.[6]VanBuren, C. A., & Everts, H. B. (2022). Vitamin A in skin and hair: an update. Nutrients, 14(14), 2952. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142952

This leads to a somewhat paradoxical situation, as retinoic acid is necessary for hair growth, but it can also cause hair loss when present in high concentrations. Thus, the therapeutic use of retinoic acid in treating hair loss is a challenging prospect.[7]Sadgrove, N. J., & Simmonds, M. S. (2021). Topical and nutricosmetic products for healthy hair and dermal antiaging using “dual‐acting”(2 for 1) plant‐based peptides, hormones, and … Continue reading

That said, several studies have shown that the application of tretinoin, a type of retinoic acid, has beneficial effects in treating hair loss. One study was conducted on 56 patients with AGA, who were treated with either a placebo, 0.5% minoxidil, 0.025% tretinoin, or a combination of minoxidil and tretinoin.[8]Bazzano, G. S., Terezakis, N., & Galen, W. (1986). Topical tretinoin for hair growth promotion. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 15(4), 880-893. Available at: … Continue reading Tretinoin treatment alone was shown to stimulate some hair regrowth in more than half of the patients who received the treatment. Further positive results were observed with combination treatment.

Figure 1: Level of hair regrowth after treatment with either a placebo, minoxidil (0.5%), tretinoin (0.025%), or a combination of tretinoin and minoxidil.[9]Bazzano, G. S., Terezakis, N., & Galen, W. (1986). Topical tretinoin for hair growth promotion. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 15(4), 880-893. Available at: … Continue reading

This was also shown in a study conducted on 31 male patients with AGA. The study showed that once-daily application of tretinoin and minoxidil, in combination, was as effective at treating hair loss as twice-daily minoxidil on its own (Figure 1).[10]Shin, H. S., Won, C. H., Lee, S. H., Kwon, O. S., Kim, K. H., & Eun, H. C. (2007). Efficacy of 5% minoxidil versus combined 5% minoxidil and 0.01% tretinoin for male pattern hair loss: a … Continue reading

Figure 2: The effect of combined minoxidil and tretinoin or minoxidil alone on hair growth parameters.[11]Shin, H. S., Won, C. H., Lee, S. H., Kwon, O. S., Kim, K. H., & Eun, H. C. (2007). Efficacy of 5% minoxidil versus combined 5% minoxidil and 0.01% tretinoin for male pattern hair loss: a … Continue reading

What is the Evidence for Targeting CRABP2 for Hair Loss?

Collectively, the evidence does suggest that CRABP2 and retinoic acid are key factors in hair loss. Owing to this, it is feasible that genetic variation in CRABP2 could influence the efficacy of hair loss treatments.

In a study conducted on newborn babies, it was found that the rs12724719 polymorphism was linked to retinoic acid levels. Specifically, those with the AA genotype had a greater concentration of retinoic acid in the blood of their umbilical cord than those with the GA or GG genotypes. It is believed that such an increase in retinoic acid may have been caused by reduced CRABP2 expression, impairing its ability to transport retinoic acid into the nucleus of the cell.[12]Manolescu, D. C., El-Kares, R., Lakhal-Chaieb, L., Montpetit, A., Bhat, P. V., & Goodyer, P. (2010). Newborn serum retinoic acid level is associated with variants of genes in the retinol … Continue reading

Although this study was conducted in newborn umbilical cord blood, and so is probably not representative of how the genetic variant affects adults or hair, the results are still interesting. If adults with the AA genotype also exhibit increased levels of retinoic acid, then therapeutic supplementation with retinoic acid to treat hair loss may be less effective in those individuals. Moreover, given that retinoic acid levels are already high, increasing levels further may increase the risk of those individuals experiencing retinoic acid-induced hair loss, as discussed earlier.

A separate study was conducted on over 25,000 patients with AGA, a mix of both males and females. Interestingly, their analysis revealed an association between the rs12724719 polymorphism and AGA. Unfortunately, the authors did not specifically state which of the genotypes were linked to AGA and which were not. However, this is yet another indication that genetic variation in CRABP2 and the rs12724719 polymorphism may influence hair health and treatments.[13]Francès, M. P., Vila-Vecilla, L., Russo, V., Caetano Polonini, H., & de Souza, G. T. (2024). Utilising SNP Association Analysis as a Prospective Approach for Personalising Androgenetic Alopecia … Continue reading

What Do Your Genetic Results Mean?

Your Result CRABP2 (rs12724719)

Variant 1 – GG genotype

Variant 2 – GA genotype Variant 3 – AA genotype

What it Means Associated with normal levels of retinoic acid in the blood Associated with normal levels of retinoic acid in the blood Associated with elevated levels of retinoic acid in the blood The Implication May benefit from retinoic acid supplementation May benefit from retinoic acid supplementation May not benefit from retinoic acid treatment (i.e, vitamin A supplementation or retinoid topicals) What Relevance Does CRABP2 Have for Hair Loss Treatment?

We have also created a rubric that helps to determine the relevance of a specific gene to hair loss based on the quality of the evidence in the above studies.

On a scale of 1-5, how important are these genetic results? (1 is the lowest, 5 is the highest)

This score is a rating based on evidence quality.

- Does this gene have any potential relevance for hair loss? (1 point)

Yes. CRABP2 has been found to be upregulated in patients with alopecia areata (score = 1)

- Does the totality of evidence implicate CRABP2 as a causal agent for hair loss? (1 point)

No. There is very little published literature that indicates CRABP2 causes hair loss. (score = 0)

- Does the totality of evidence implicate CRABP2 as a predictive factor for hair loss treatment responsiveness? (2 points)

No. There is no published literature that shows that CRABP2 polymorphisms affect hair loss treatments (score = 0)

- Is this quality of evidence on (3) strong enough to influence treatment recommendations? (1 point)

Since CRABP2 fails question #3, it cannot be awarded points for question #4 (score = 0)

Total Score = 1

Final Thoughts

While there is evidence that genetic variation in CRABP2 is associated with AGA and may affect retinoic acid levels, the evidence is not yet sufficient to make definitive treatment recommendations based solely on genotype. Importantly, no studies have yet explored how genetic variation in CRABP2 affects treatment with retinoic acid or any other therapeutic. Additional studies that seek to answer this question must be conducted to confirm the true predictive value of testing CRABP2 variants to personalize hair treatments.

References[+]

References ↑1 Wei, L. N. (2016). Cellular retinoic acid binding proteins: Genomic and non-genomic functions and their regulation. The Biochemistry of Retinoid Signaling II: The Physiology of Vitamin A-Uptake, Transport, Metabolism and Signaling, 163-178. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-0945-1_6 ↑2 He, M., Lv, X., Cao, X., Yuan, Z., Quan, K., Getachew, T., Mwacharo, J.M., Haile, A., Li, Y., Wang, S. and Sun, W. (2023). CRABP2 Promotes the Proliferation of Dermal Papilla Cells via the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Animals, 13(12), 2033. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13122033 ↑3 Duncan, F.J., Silva, K.A., Johnson, C.J., King, B.L., Szatkiewicz, J.P., Kamdar, S.P., Ong, D.E., Napoli, J.L., Wang, J., King Jr, L.E. and Whiting, D.A. (2013). Endogenous retinoids in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 133(2), 334-343. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2012.344 ↑4 Li, M., Chiba, H., Warot, X., Messaddeq, N., Gérard, C., Chambon, P., & Metzger, D. (2001). RXRα ablation in skin keratinocytes results in alopecia and epidermal alterations. Development, 128(5), 675-688. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.128.5.675 ↑5 Ho, B.S.Y., Vaz, C., Ramasamy, S., Chew, E.G.Y., Mohamed, J.S., Jaffar, H., Hillmer, A., Tanavde, V., Bigliardi-Qi, M. and Bigliardi, P.L. (2019). Progressive expression of PPARGC1α is associated with hair miniaturization in androgenetic alopecia. Scientific reports, 9(1), 8771. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43998-7 ↑6 VanBuren, C. A., & Everts, H. B. (2022). Vitamin A in skin and hair: an update. Nutrients, 14(14), 2952. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142952 ↑7 Sadgrove, N. J., & Simmonds, M. S. (2021). Topical and nutricosmetic products for healthy hair and dermal antiaging using “dual‐acting”(2 for 1) plant‐based peptides, hormones, and cannabinoids. FASEB BioAdvances, 3(8), 601. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1096/fba.2021-00022 ↑8, ↑9 Bazzano, G. S., Terezakis, N., & Galen, W. (1986). Topical tretinoin for hair growth promotion. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 15(4), 880-893. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0190-9622(86)80024-X ↑10, ↑11 Shin, H. S., Won, C. H., Lee, S. H., Kwon, O. S., Kim, K. H., & Eun, H. C. (2007). Efficacy of 5% minoxidil versus combined 5% minoxidil and 0.01% tretinoin for male pattern hair loss: a randomized, double-blind, comparative clinical trial. American journal of clinical dermatology, 8, 285-290. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2165/00128071-200708050-00003 ↑12 Manolescu, D. C., El-Kares, R., Lakhal-Chaieb, L., Montpetit, A., Bhat, P. V., & Goodyer, P. (2010). Newborn serum retinoic acid level is associated with variants of genes in the retinol metabolism pathway. Pediatric research, 67(6), 598-602. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181dcf18a ↑13 Francès, M. P., Vila-Vecilla, L., Russo, V., Caetano Polonini, H., & de Souza, G. T. (2024). Utilising SNP Association Analysis as a Prospective Approach for Personalising Androgenetic Alopecia Treatment. Dermatology and Therapy, 14(4), 971-981. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-024-01142-y CYP19A1 is a gene within the cytochrome P450 superfamily, a large network of genes that regulate various critical processes throughout the body. CYP19A1 encodes the protein aromatase, which is involved in the conversion of androgens, such as testosterone, into estrogens. Aromatase is believed to play a key role in regulating hair growth, and several studies have also linked aromatase activity to hair loss. A handful of studies have also investigated genetic variation in CYP19A1, suggesting that some variants may cause differential responses to hair loss treatments. This article will explore how relevant CYP19A1 is to hair treatment effectiveness and how to interpret your genetic results to make the correct treatment choice.

Interested in Topical Finasteride?

Low-dose & full-strength finasteride available, if prescribed*

Take the next step in your hair regrowth journey. Get started today with a provider who can prescribe a topical solution tailored for you.

*Only available in the U.S. Prescriptions not guaranteed. Restrictions apply. Off-label products are not endorsed by the FDA.

What Is CYP19A1?

Cytochrome P450 Family 19 Subfamily A Member 1, known as CYP19A1, is part of the cytochrome P450 superfamily. The human genome contains at least 57 genes that belong to various CYP sub-families, collectively regulating several critical roles throughout the body. CYP19A1 encodes the protein aromatase, an enzyme involved in converting androgens to estrogens, such as androgen, into estradiol. For this reason, aromatase is also known as estrogen synthase.[1]Nebert, D. W., Wikvall, K., & Miller, W. L. (2013). Human cytochromes P450 in health and disease. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368(1612), 20120431. … Continue reading

Many studies have linked aromatase as a key regulatory factor in hair growth for several years. One such study was conducted on growing (anagen) phase hairs taken from female participants with and without female pattern hair loss (FPHL). Analysis of the hairs revealed that CYP19A1 expression was significantly lower in the participants with FPHL.[2]Sánchez, P., Serrano-Falcón, C., Torres, J. M., Serrano, S., & Ortega, E. (2018). 5α-Reductase isozymes and aromatase mRNA levels in plucked hair from young women with female pattern hair … Continue reading

Similarly, another study measured the aromatase levels in the hair follicles of men and women with androgenic alopecia (AGA). The follicles were taken from different regions of the head, revealing that aromatase levels were higher in the occipital (non-balding) region than in the frontal (balding) region. This difference was identified in both males and females. Still, interestingly, it was also found that aromatase levels were six times higher in the frontal hair follicles of women than in men. This could explain the differences in male and female hair loss patterns.[3]Sawaya, M. E., & Price, V. H. (1997). Different levels of 5α-reductase type I and II, aromatase, and androgen receptor in hair follicles of women and men with androgenetic alopecia. Journal of … Continue reading

Figure 1: Differences in aromatase activity in men and women.[4]Sawaya, M. E., & Price, V. H. (1997). Different levels of 5α-reductase type I and II, aromatase, and androgen receptor in hair follicles of women and men with androgenetic alopecia. Journal of … Continue reading

Associations between aromatase and hair loss have been underlined by the discovery that aromatase inhibitors can lead to the thinning and loss of hair. An analysis of 851 female breast cancer survivors revealed that those who underwent aromatase inhibitor therapy were significantly more likely to report hair loss and hair thinning than those who did not. Moreover, this association was independent of factors such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, highlighting the importance of aromatase.[5]Gallicchio, L., Calhoun, C., & Helzlsouer, K. J. (2013). Aromatase inhibitor therapy and hair loss among breast cancer survivors. Breast cancer research and treatment, 142, 435-443. Available at: … Continue reading

Although not yet fully understood, the role of aromatase in hair loss is thought to be based on its influence on estrogen, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). In converting testosterone to estradiol, aromatase reduces testosterone levels and, importantly, reduces the amount of testosterone converted to DHT. High levels of DHT have been implicated in the pathogenesis of AGA. These interactions could explain the association between reduced aromatase activity and hair loss.[6]Rossi, A., Caro, G., Magri, F., Fortuna, M. C., & Carlesimo, M. (2021). Clinical aspect, pathogenesis and therapy options of alopecia induced by hormonal therapy for breast cancer. Exploration of … Continue reading

Indeed, it has been shown that aromatase inhibition in mice led to decreased levels of estradiol (a form of estrogen) and increased levels of DHT.[7]Iqbal, R., Jain, G. K., Siraj, F., & Vohora, D. (2018). Aromatase inhibition by letrozole attenuates kainic acid-induced seizures but not neurotoxicity in mice. Epilepsy Research, 143, 60-69. … Continue reading Similar results were reported in men, with aromatase inhibition leading to increased levels of testosterone and DHT. However, it should be noted that this study was conducted on older men who generally have lower levels of testosterone, so the results may not be representative of testosterone modulation in the wider population.[8]Leder, B. Z., Rohrer, J. L., Rubin, S. D., Gallo, J., & Longcope, C. (2004). Effects of aromatase inhibition in elderly men with low or borderline-low serum testosterone levels. The Journal of … Continue reading

Figure 2: Effect of anastrozole (an aromatase inhibitor) on serum testosterone, free testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone in men aged 62-74 years.[9]Leder, B. Z., Rohrer, J. L., Rubin, S. D., Gallo, J., & Longcope, C. (2004). Effects of aromatase inhibition in elderly men with low or borderline-low serum testosterone levels. The Journal of … Continue reading

A recent study has even suggested that Minoxidil, the first FDA-approved treatment for AGA, may exert its effects via interaction with aromatase. They found that Minoxidil increases the activity of aromatase, suggesting that Minoxidil may help to treat AGA by increasing the production of estradiol and decreasing the production of DHT.[10]Shen, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhang, L., Sun, J., Xie, B., Zhang, H., & Song, X. (2023). New target for minoxidil in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Drug Design, Development and Therapy, 2537-2547. … Continue reading

Figure 3: Human epidermal-dermal papilla cells treated with minoxidil showed an increase in mRNA levels of CYP19A1, indicating that it enhances the activity of aromatase.[11]Shen, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhang, L., Sun, J., Xie, B., Zhang, H., & Song, X. (2023). New target for minoxidil in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Drug Design, Development and Therapy, 2537-2547. … Continue reading

What Is The Evidence for Targeting CYP19A1 For Hair Loss?

Collectively, a significant amount of evidence suggests that aromatase is a key factor in hair loss. Owing to this, it is feasible that genetic variation in CYP19A1 could influence the efficacy of hair loss treatments.

In a study conducted on patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), the rs2470152 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in CYP19A1 was suggested to be associated with decreased aromatase activity. Namely, participants with PCOS and the TC genotype were found to exhibit increased levels of testosterone and a reduced ratio of estradiol to testosterone. In participants without PCOS, those with the TC genotype also exhibited a lower ratio of estradiol to testosterone.[12]Zhang, X.L., Zhang, C.W., Xu, P., Liang, F.J., Che, Y.N., Xia, Y.J., Cao, Y.X., Wu, X.K., Wang, W.J., Yi, L. and Gao, Q. (2012). SNP rs2470152 in CYP19 is correlated to aromatase activity in Chinese … Continue reading

Figure 4: Characteristics and serum hormone concentrations in different genotypes of women with and without PCOS. Of interest is the TC genotype; participants exhibited an increased level of estradiol (E2) and a decreased E2/T ratio (meaning increased testosterone and decreased estradiol).[13]Zhang, X.L., Zhang, C.W., Xu, P., Liang, F.J., Che, Y.N., Xia, Y.J., Cao, Y.X., Wu, X.K., Wang, W.J., Yi, L. and Gao, Q. (2012). SNP rs2470152 in CYP19 is correlated to aromatase activity in Chinese … Continue reading

People with the TC genotype may benefit from treatment with estradiol or anti-androgen drugs, given the associations between low estrogen levels, high androgen levels, and hair loss. However, it should be noted that this study was conducted on participants with PCOS; the rs2470152 SNP has not been linked to AGA or other types of hair loss, meaning it may not affect their treatment.

Furthermore, as stated earlier, the relationship between estrogen androgen levels and hair loss is still not understood. Although associations between low estrogen levels and hair loss have been identified, so too have associations between high estrogen levels and hair loss. A study involving 955 females discovered that participants with the rs4646 SNP CC genotype had an increased risk of developing FPHL.[14]Yip, L., Zaloumis, S., Irwin, D., Severi, G., Hopper, J., Giles, G., Harrap, S., Sinclair, R. and Ellis, J. (2009). Gene‐wide association study between the aromatase gene (CYP19A1) and female … Continue reading

Interestingly, the rs4646 SNP CC genotype had previously been shown to be associated with higher estrogen levels in postmenopausal females.[15]Haiman, C.A., Dossus, L., Setiawan, V.W., Stram, D.O., Dunning, A.M., Thomas, G., Thun, M.J., Albanes, D., Altshuler, D., Ardanaz, E. and Boeing, H. (2007). Genetic variation at the CYP19A1 locus … Continue reading The suggestion that higher estrogen levels may increase the risk of developing FPHL contradicts previous literature on the subject, indicating that genetics alone are not sufficient to make treatment recommendations.

Another study investigated the effects of genetic variation on dutasteride treatment, a drug used off-label in treating hair loss. They identified a positive association between the rs700519 SNP in CYP19A1 and the efficacy of dutasteride; in other words, people with this genetic variant responded better to treatment.[16]Rhie, A., Son, H.Y., Kwak, S.J., Lee, S., Kim, D.Y., Lew, B.L., Sim, W.Y., Seo, J.S., Kwon, O., Kim, J.I. and Jo, S.J. (2019). Genetic variations associated with response to dutasteride in the … Continue reading

Figure 5: Genotypic landscape of 42 patients, the cumulative effect of each allele count, and their positive or negative effect. Boxes represent SNPs that exhibited a positive (blue) or negative (red) effect on the patient’s response to dutasteride. Light-colored boxes represent heterozygous SNPs (a variation where an individual has two different versions of a specific DNA sequence at a particular location in the genome), dark-colored boxes represent homozygous SNPs (a variation where an individual has two identical versions of a specific DNA sequence at a particular location in the genome). Patient responses to dutasteride improve from left to right.[17]Rhie, A., Son, H.Y., Kwak, S.J., Lee, S., Kim, D.Y., Lew, B.L., Sim, W.Y., Seo, J.S., Kwon, O., Kim, J.I. and Jo, S.J. (2019). Genetic variations associated with response to dutasteride in the … Continue reading

Despite this positive association, some patients classified as ‘poor responders’ also had the rs700519 SNP. This indicates that having a ‘positive’ SNP in CYP19A1 does not guarantee that you will respond well to dutasteride. Rather, the study presents the likelihood that the combination of SNPs that one possesses is more important.

What Do Your Genetic Results Mean?

Your Result CYP19A1 (rs2470152)

Variant 1 – TT genotype Variant 2 – CC genotype Variant 3 – TC genotype

What it means Not associated with a change in testosterone or estrogen levels Not associated with a change in testosterone or estrogen levels Associated with reduced expression of CYP19A1 and, therefore, an increase in testosterone levels/decrease in estrogen levels The Implication May not benefit from estradiol or anti-androgens May not benefit from estradiol or anti-androgens May benefit from treatment with estradiol as a replacement hormone or anti-androgen drugs Your Result CYP19A1 (rs700519)

Variant 1 – CC genotype

Variant 2 – CT genotype Variant 3 – TT genotype

What it means May be a normal/poor responder to 5α-reductase inhibitors May be a good responder to 5α-reductase inhibitors May be a good responder to 5α-reductase inhibitors The Implication May be a good candidate for typical/higher dosages of 5α-reductase inhibitors May be a good candidate for lower dosages of 5α-reductase inhibitors May be a good candidate for lower dosages of 5α-reductase inhibitors What Relevance Does CYp19A1 Have For Hair Loss Treatment?

We have also created a rubric that helps to determine the relevance of a specific gene to hair loss based on the quality of the evidence in the above studies.

On a scale of 1-5, how important are these genetic results? (1 is the lowest, 5 is the highest)

This score is a rating based on evidence quality.

- Does this gene have any potential relevance for hair loss? (1 point)

Yes. A decrease in aromatase may lead to an increase in testosterone and, subsequently, DHT, which are linked with androgenetic alopecia. (score=1)

- Does the totality of evidence implicate CYP19A1 as a causal agent for hair loss? (1 point)

While there are some hypotheses about how SNPs in CYP19A1 may lead to hair loss, there is no published evidence showing this possible association. (score = 0)

- Does the totality of evidence implicate CYP19A1 as a predictive factor for hair loss treatment responsiveness? (2 points)

No, the data does not suggest that CYP19A1 can be used as a predictor for hair loss treatment responsiveness. (score = 0)

- Is this quality of evidence on (3) strong enough to influence treatment recommendations? (1 point)

Since CYP19A1 fails question #3, it cannot be awarded points for question #4 (score = 0)

Total Score = 1

Final Thoughts

While one small study suggests that genetic variation in CYP19A1 may influence your response to treatment with a 5α-reductase inhibitor, the evidence is not yet strong enough to make definitive treatment recommendations based solely on genotype. Furthermore, some evidence regarding CYP19A1 and its associations with hair loss conditions is contradictory. Larger and more robust studies are needed to confirm the true predictive value of genetic testing for CYP19A1 variants to personalize hair loss treatments.

References[+]

References ↑1 Nebert, D. W., Wikvall, K., & Miller, W. L. (2013). Human cytochromes P450 in health and disease. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 368(1612), 20120431. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0431 ↑2 Sánchez, P., Serrano-Falcón, C., Torres, J. M., Serrano, S., & Ortega, E. (2018). 5α-Reductase isozymes and aromatase mRNA levels in plucked hair from young women with female pattern hair loss. Archives of dermatological research, 310, 77-83. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-017-1798-0 ↑3, ↑4 Sawaya, M. E., & Price, V. H. (1997). Different levels of 5α-reductase type I and II, aromatase, and androgen receptor in hair follicles of women and men with androgenetic alopecia. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 109(3), 296-300. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/1523-1747.ep12335779 ↑5 Gallicchio, L., Calhoun, C., & Helzlsouer, K. J. (2013). Aromatase inhibitor therapy and hair loss among breast cancer survivors. Breast cancer research and treatment, 142, 435-443. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2744-2 ↑6 Rossi, A., Caro, G., Magri, F., Fortuna, M. C., & Carlesimo, M. (2021). Clinical aspect, pathogenesis and therapy options of alopecia induced by hormonal therapy for breast cancer. Exploration of Targeted Anti-tumor Therapy, 2(5), 490. Available at: https://doi.org/10.37349/etat.2021.00059 ↑7 Iqbal, R., Jain, G. K., Siraj, F., & Vohora, D. (2018). Aromatase inhibition by letrozole attenuates kainic acid-induced seizures but not neurotoxicity in mice. Epilepsy Research, 143, 60-69. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.04.004 ↑8, ↑9 Leder, B. Z., Rohrer, J. L., Rubin, S. D., Gallo, J., & Longcope, C. (2004). Effects of aromatase inhibition in elderly men with low or borderline-low serum testosterone levels. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 89(3), 1174-1180. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2003-031467 ↑10, ↑11 Shen, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhang, L., Sun, J., Xie, B., Zhang, H., & Song, X. (2023). New target for minoxidil in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Drug Design, Development and Therapy, 2537-2547. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S427612 ↑12, ↑13 Zhang, X.L., Zhang, C.W., Xu, P., Liang, F.J., Che, Y.N., Xia, Y.J., Cao, Y.X., Wu, X.K., Wang, W.J., Yi, L. and Gao, Q. (2012). SNP rs2470152 in CYP19 is correlated to aromatase activity in Chinese polycystic ovary syndrome patients. Molecular Medicine Reports, 5(1), 245-249. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2011.616 ↑14 Yip, L., Zaloumis, S., Irwin, D., Severi, G., Hopper, J., Giles, G., Harrap, S., Sinclair, R. and Ellis, J. (2009). Gene‐wide association study between the aromatase gene (CYP19A1) and female pattern hair loss. British Journal of Dermatology, 161(2), 289-294. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09186.x ↑15 Haiman, C.A., Dossus, L., Setiawan, V.W., Stram, D.O., Dunning, A.M., Thomas, G., Thun, M.J., Albanes, D., Altshuler, D., Ardanaz, E. and Boeing, H. (2007). Genetic variation at the CYP19A1 locus predicts circulating estrogen levels but not breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. Cancer research, 67(5), 1893-1897. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4123 ↑16, ↑17 Rhie, A., Son, H.Y., Kwak, S.J., Lee, S., Kim, D.Y., Lew, B.L., Sim, W.Y., Seo, J.S., Kwon, O., Kim, J.I. and Jo, S.J. (2019). Genetic variations associated with response to dutasteride in the treatment of male subjects with androgenetic alopecia. Plos one, 14(9), e0222533. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222533 COL1A1 is a gene within the collagen superfamily, a large network that comprises at least 44 genes and 28 proteins. The collagen proteins have a variety of roles, with perhaps their most crucial being to support the structure of tissues throughout the body. COL1A1 and COL1A2 produce the protein chains that combine to form type 1 collagen, the most abundant type of collagen in the body, which has also been linked to regulating hair growth. Moreover, some studies have suggested that genetic variation in COL1A1 may cause differential responses to hair loss treatment.

This article will explore how relevant COL1A1 is to hair treatment effectiveness and how to interpret your genetic results to make the correct treatment choice.

All-Natural Hair Supplement

The top natural ingredients for hair growth, all in one supplement.

Take the next step in your hair growth journey with a world-class natural supplement. Ingredients, doses, & concentrations built by science.

What Is COL1A1?

Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain, or COL1A1, is part of the collagen superfamily. There are 44 genes encoding the proteins that make up the 28 different types of collagen, with some collagen types consisting of more than one protein (α chain).[1]Ricard-Blum, S. (2011). The collagen family. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 3(1), a004978. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a004978 Collagens have a variety of key roles throughout the body, foremost of which is the promotion of cell growth and supporting the structure and organization of tissues.[2]Sun, H., Wang, Y., Wang, S., Xie, Y., Sun, K., Li, S., Cui, W. and Wang, K. (2023). The involvement of collagen family genes in tumor enlargement of gastric cancer. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 100. … Continue reading

Type 1 collagen (COL1) is the most abundant of all collagen types within the body, representing over a quarter of the total protein content in mammals. It consists of two α1 chains, produced by COL1A1, and one α2 chain, produced by Collagen Type I Alpha 2 Chain (COL1A2). The three α chains assemble into a single procollagen and undergo multiple rounds of modification, with several molecules eventually assembling into a longer collagen fibril and, finally, a type 1 collagen fiber (Figure 1).[3]Kruger, T. E., Miller, A. H., & Wang, J. (2013). Collagen scaffolds in bone sialoprotein‐mediated bone regeneration. The Scientific World Journal, 2013(1), 812718. Available at: … Continue reading

Figure 1: How Type I Collagen is Made in the Body. (a) The process starts with three protein chains: two identical α1(I) chains and one α2(I) chain. (b) These three chains twist together to form a structure called procollagen. (c) An enzyme called procollagen peptidase comes along and snips off the loose ends of the procollagen.(d) After the trimming, what’s left is called a tropocollagen molecule. This is the basic building block of collagen. (e) Multiple tropocollagen molecules then line up and stick together, forming a thin strand called a collagen fibril. This fibril keeps growing as more tropocollagen molecules join in. (f) Finally, many of these collagen fibrils bundle together to create a sturdy collagen fiber. This is the form of collagen that gives strength to our skin, bones, and other tissues.[4]Kruger, T. E., Miller, A. H., & Wang, J. (2013). Collagen scaffolds in bone sialoprotein‐mediated bone regeneration. The Scientific World Journal, 2013(1), 812718. Available at: … Continue reading

Given its abundance within the body, it is hardly surprising that COL1 has been detected in the scalp. Specifically, the connective tissue sheath surrounding the hair follicle was found to be a major source of type 1 procollagen, expressing greater amounts than other parts of the follicle. Moreover, they showed that the expression of type 1 collagen changes throughout the hair cycle, collectively indicating that type 1 collagen may play a key role in the growth and structure of hair follicles.[5]Oh, J.K., Kwon, O.S., Kim, M.H., Jo, S.J., Han, J.H., Kim, K.H., Eun, H.C. and Chung, J.H. (2012). Connective tissue sheath of hair follicle is a major source of dermal type I procollagen in human … Continue reading

These results support an earlier study that found that Col1 levels in mice also changed based on the stage of the hair cycle. They found that levels of Col1 were approximately two-fold higher in the dermis of the skin in the anagen (growing) phase than skin in the telogen (resting) phase. Furthermore, they found that Col1 molecules underwent more modifications during the anagen phase. This indicates that the remodeling of collagen is more active in anagen skin, which may support the growth and migration of hair follicles.[6]Yamamoto, & Yamauchi. (1999). Characterization of dermal type I collagen of C3H mouse at different stages of the hair cycle. British Journal of Dermatology, 141(4), 667-675. Available at: … Continue reading

What is the Evidence for Targeting COL1A1 For Hair Loss?

Although only a few studies have investigated COL1 in relation to hair health, the evidence they have provided is robust and certainly suggests that COL1 may well be an important factor in regulating hair growth. Owing to this, it is feasible that genetic variation in COL1A1 could influence hair loss treatments.

Research into the rs1800012 polymorphism of Col1 revealed that people with the GT genotype had a higher ratio of COL1A1:COL1A2 gene expression and α1:α2 chains than the GG genotype. Generally existing in a 2:1 ratio, due to the structure of COL1, any increase in this ratio would lead to an imbalance between the two types of α chain.[7]Mann, V., Hobson, E.E., Li, B., Stewart, T.L., Grant, S.F., Robins, S.P., Aspden, R.M. and Ralston, S.H. (2001). A COL1A1 Sp1 binding site polymorphism predisposes to osteoporotic fracture by … Continue reading

This could lead to instability of the collagen molecules, indicating that it may be useful for people who exhibit this genotype to take supplements that might support collagen synthesis, such as silicon, cysteine, or collagen.

Figure 2: Collagen protein and mRNA levels in osteoblasts (cells that form new bones) cultured from patients with different genotypes. Different genotypes of the rs1800012 polymorphism are shown. SS genotype = GG genotype; Ss genotype = GT genotype.[8]Mann, V., Hobson, E.E., Li, B., Stewart, T.L., Grant, S.F., Robins, S.P., Aspden, R.M. and Ralston, S.H. (2001). A COL1A1 Sp1 binding site polymorphism predisposes to osteoporotic fracture by … Continue reading

Furthermore, in an analysis of over 26,000 people, it was found that the rs1800012 polymorphism is associated with AGA. Unfortunately, the study does not state which specific genotypes are associated with AGA, but this does suggest that the rs1800012 polymorphism and COL1A1 play a role in hair loss. [9]Francès, M. P., Vila-Vecilla, L., Russo, V., Caetano Polonini, H., & de Souza, G. T. (2024). Utilising SNP Association Analysis as a Prospective Approach for Personalising Androgenetic Alopecia … Continue reading

It has also been found that COL1A1 expression is upregulated in people with AGA. However, the upregulation of COL1A1 was not linked to the rs1800012 polymorphism. Moreover, the same study also showed that the expression of COL1A2 is upregulated in people with AGA, which may cause the α1:α2 chain ratio to remain unchanged.[10]Michel, L., Reygagne, P., Benech, P., Jean‐Louis, F., Scalvino, S., Ly Ka So, S., Hamidou, Z., Bianovici, S., Pouch, J., Ducos, B. and Bonnet, M., 2017. Study of gene expression alteration in male … Continue reading

Together, although these studies do suggest that COL1A1 and the rs1800012 polymorphism may be involved in hair loss, they also indicate that the underlying mechanism is not understood. Further studies are required to understand how the expression of COL1A1 and COL1A2, the rs1800012 polymorphism, and the α1:α2 chain ratio link to hair loss and AGA.

What Do Your Genetic Results Mean?

Your Result

COL1A1 (rs1800012) Variant 1 – GG genotype Variant 2 – GT genotype What it means Normal α1 chain synthesis Increased α1 chain synthesis The Implication May not benefit from supplementation that supports collagen formation May benefit from supplementation that supports collagen formation, such as adenosine or cysteine

What Relevance Does COL1A1 Have for Hair Loss Treatment?

We have also created a rubric that helps to determine the relevance of a specific gene to hair loss based on the quality of the evidence in the above studies.

On a scale of 1-5, how important are these genetic results? (1 is the lowest, 5 is the highest)

This score is a rating based on evidence quality.

- Does this gene have any potential relevance for hair loss? (1 point)

Yes, COL1A1 and COL1A2 have been found to be overexpressed in patients with androgenetic alopecia (score=1)

- Does the totality of evidence implicate COL1A1 as a causal agent for hair loss? (1 point)

No, there is no published evidence to suggest that COL1A1 polymorphisms can cause hair loss (score = 0)

- Does the totality of evidence implicate COL1A1 as a predictive factor for hair loss treatment responsiveness? (2 points)

No, there is no data to suggest that COL1A1 polymorphisms can be used as a predictor for hair loss treatment responsiveness (score = 0)

- Is this quality of evidence on (3) strong enough to influence treatment recommendations? (1 point)

Since COL1A1 fails question #3, it cannot be awarded points for question #4 (score = 0)

Total Score = 1

Final Thoughts

While there is some evidence to suggest that genetic variation in COL1A1 may influence your response to treatment with collagen supplements, there is not yet strong enough evidence to make definitive treatment recommendations based solely on genotype. Furthermore, it is evident that the association(s) between COL1A1, rs1800012, and hair loss are not yet understood. Larger and more robust studies are needed to confirm the true predictive value of genetic testing for COL1A1 variants to personalize hair loss treatments.

References[+]