- About

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Education.

Prioritize knowledge. Make better choices.

- Evidence.

Sort good studies from the bad.

- Regrowth.

Get bigger hair gains.

Team MembersPhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Rob English

Founder, researcher, & consumer advocate

- Research Team

Our team of PhD’s, researchers, & more

Editorial PolicyDiscover how we conduct our research.

ContactHave questions? Contact us.

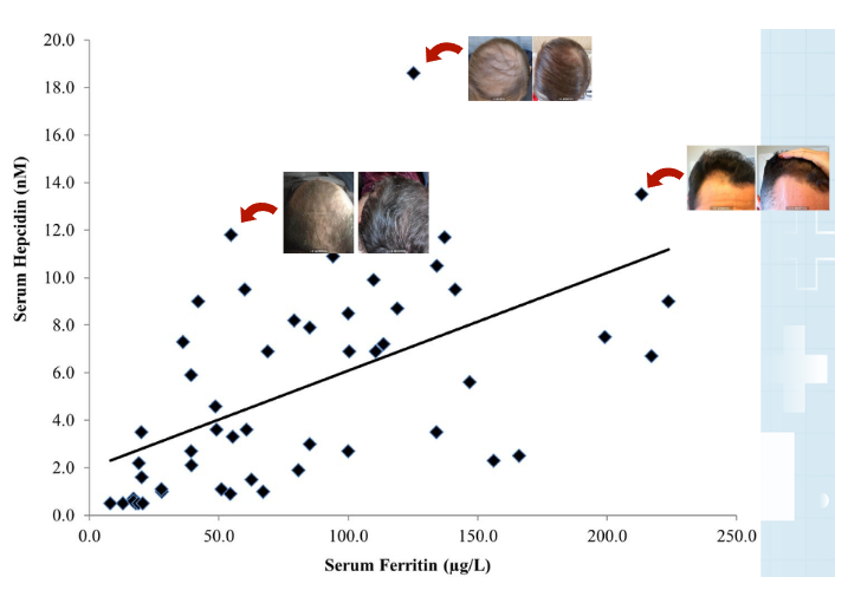

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

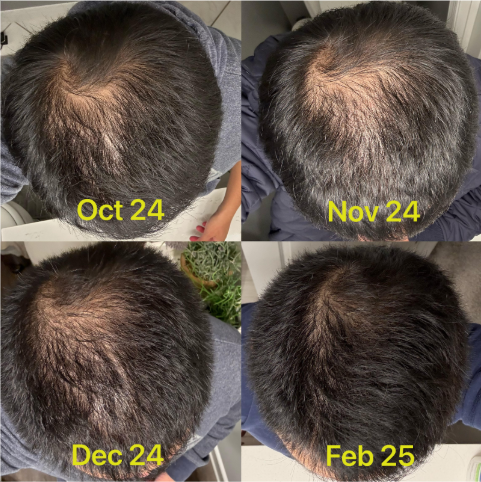

- — Jenna, 31, U.S.A.

I have attached my before and afters of my progress since joining this group...

- — Tom, 30, U.K.

I’m convinced I’ve recovered to probably the hairline I had 3 years ago. Super stoked…

- — Rabih, 30’s, U.S.A.

My friends actually told me, “Your hairline improved. Your hair looks thicker...

- — RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A.

I also feel my hair has a different texture to it now…

- — Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA

Firstly thank you for your work in this field. I am immensely grateful that...

- — Ben M., U.S.A

I just wanted to thank you for all your research, for introducing me to this method...

- — Raul, 50, Spain

To be honest I am having fun with all this and I still don’t know how much...

- — Lisa, 52, U.S.

I see a massive amount of regrowth that is all less than about 8 cm long...

Client Testimonials150+ member experiences.

Scroll Down

Popular Treatments- Treatments

Popular treatments. But do they work?

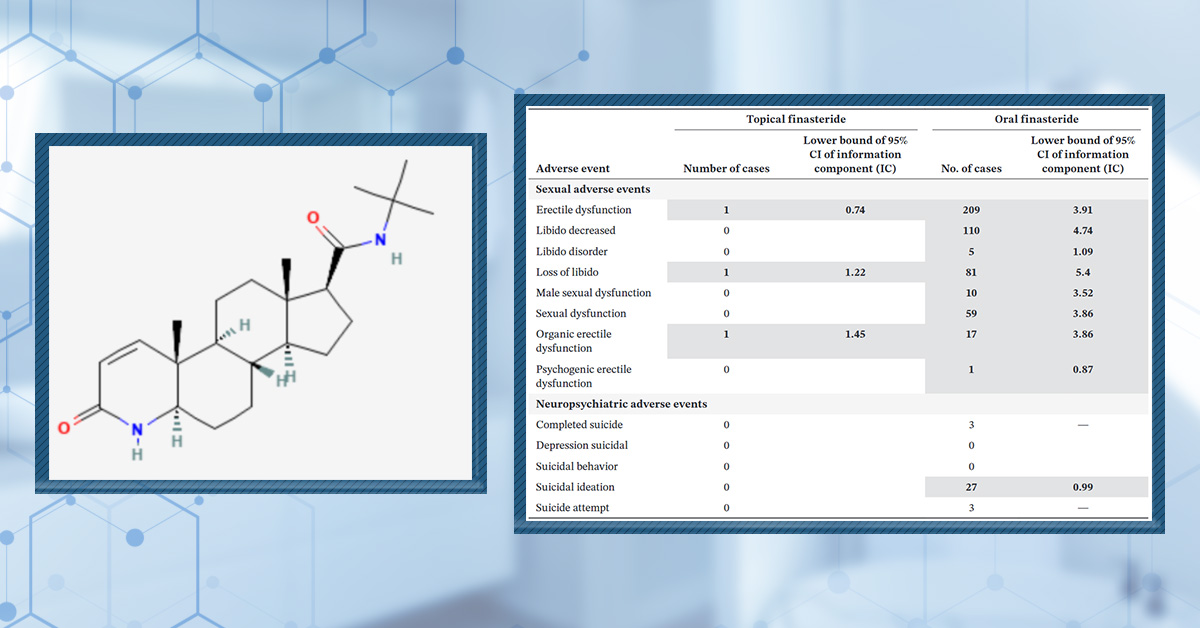

- Finasteride

- Oral

- Topical

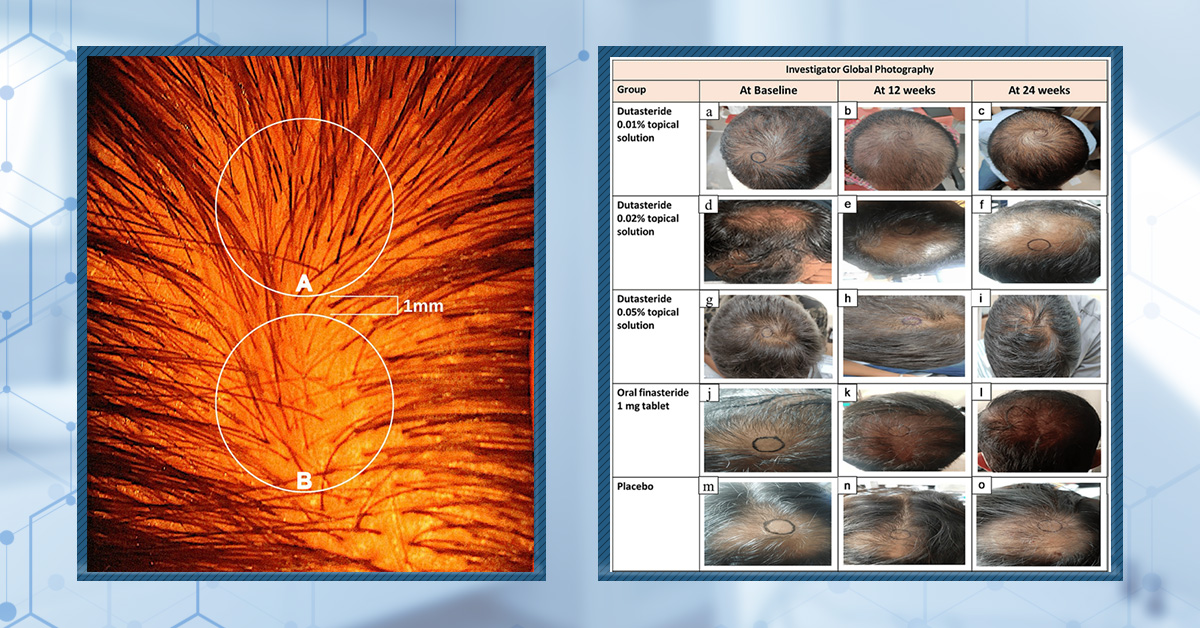

- Dutasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Mesotherapy

- Minoxidil

- Oral

- Topical

- Ketoconazole

- Shampoo

- Topical

- Low-Level Laser Therapy

- Therapy

- Microneedling

- Therapy

- Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy (PRP)

- Therapy

- Scalp Massages

- Therapy

More

IngredientsTop-selling ingredients, quantified.

- Saw Palmetto

- Redensyl

- Melatonin

- Caffeine

- Biotin

- Rosemary Oil

- Lilac Stem Cells

- Hydrolyzed Wheat Protein

- Sodium Lauryl Sulfate

More

ProductsThe truth about hair loss "best sellers".

- Minoxidil Tablets

Xyon Health

- Finasteride

Strut Health

- Hair Growth Supplements

Happy Head

- REVITA Tablets for Hair Growth Support

DS Laboratories

- FoliGROWTH Ultimate Hair Neutraceutical

Advanced Trichology

- Enhance Hair Density Serum

Fully Vital

- Topical Finasteride and Minoxidil

Xyon Health

- HairOmega Foaming Hair Growth Serum

DrFormulas

- Bio-Cleansing Shampoo

Revivogen MD

more

Key MetricsStandardized rubrics to evaluate all treatments.

- Evidence Quality

Is this treatment well studied?

- Regrowth Potential

How much regrowth can you expect?

- Long-Term Viability

Is this treatment safe & sustainable?

Free Research- Free Resources

Apps, tools, guides, freebies, & more.

- Free CalculatorTopical Finasteride Calculator

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: What Causes Hair Loss?

- Free ResourceFree Guide: Standardized Scalp Massages

- Free Course7-Day Hair Loss Email Course

- Free DatabaseIngredients Database

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: Hair Loss Disorders

- Free DatabaseTreatment Guides

- Free Lab TestsProduct Lab Tests: Purity & Potency

- Free Video & Write-upEvidence Quality Masterclass

- Free Interactive GuideDermatology Appointment Guide

More

Articles100+ free articles.

-

Hims Hair Growth Reviews: The Pros, Cons, and Real Results

-

Topical Finasteride Before and After: Real Case Studies

-

How to Reduce the Risk of Finasteride Side Effects

-

10 Best DHT-Blocking Shampoos

-

Best Minoxidil for Men: Top Picks for 2026

-

7 Best Oils for Hair Growth

-

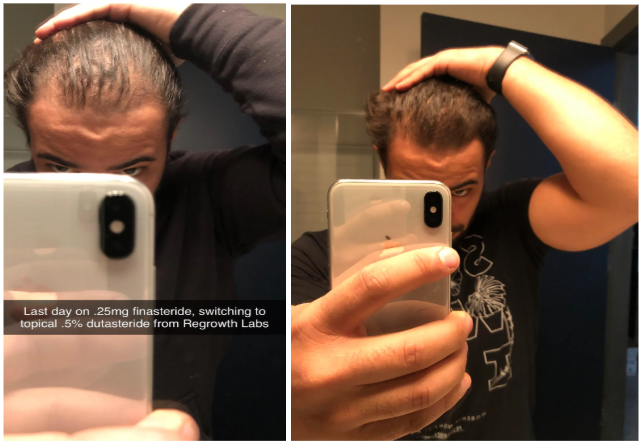

Switching From Finasteride to Dutasteride

-

Best Minoxidil for Women: Top 6 Brands of 2026

PublicationsOur team’s peer-reviewed studies.

- Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review

- Use of Botulinum Toxin for Androgenic Alopecia: A Systematic Review

- Conflicting Reports Regarding the Histopathological Features of Androgenic Alopecia

- Self-Assessments of Standardized Scalp Massages for Androgenic Alopecia: Survey Results

- A Hypothetical Pathogenesis Model For Androgenic Alopecia:Clarifying The Dihydrotestosterone Paradox And Rate-Limiting Recovery Factors

Menu- AboutAbout

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Team Members

PhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Editorial Policy

Discover how we conduct our research.

- Contact

Have questions? Contact us.

- Before-Afters

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- Client Testimonials

Read the experiences of members

Before-Afters/ Client Testimonials- Popular Treatments

-

Articles

Minoxidil is a widely used medication for treating androgenic alopecia (AGA) in both men and women. Originally developed as a treatment for high blood pressure, minoxidil was found to improve hair growth outcomes as a side effect, making its topical form one of only two (the other being finasteride) FDA-approved treatments for AGA.

Minoxidil is primarily available in two forms: topical and oral. The topical form, which includes both solutions and foams, is more commonly used and can be purchased over the counter. Oral minoxidil, however, is prescription only and is typically given at doses of 2.5 mg or 5 mg for hair loss treatment.

While minoxidil is generally considered safe, it’s important to understand its potential side effects and who might be more at risk from them. In this article, we will examine the side effects of topical and oral minoxidil and discuss how you can adjust your treatment regimen to mitigate these.

Interested in Topical Minoxidil?

High-strength topical minoxidil available, if prescribed*

Take the next step in your hair regrowth journey. Get started today with a provider who can prescribe a topical solution tailored for you.

*Only available in the U.S. Prescriptions not guaranteed. Restrictions apply. Off-label products are not endorsed by the FDA.

How Does Minoxidil Work?

Minoxidil was originally developed as an antihypertensive medication. However, when treated participants started experiencing hypertrichosis (excessive hair growth), studies were conducted to find out if it could improve hair regrowth outcomes in humans (spoiler alert – it could!).[1]Bryan, J. (2011). How minoxidil was transformed from an antihypertensive to hair-loss drug. The Pharmaceutical Journal. Available at: … Continue reading

Minoxidil’s mechanism of action is not fully understood, but it is thought to work through two main mechanisms:

- Vasodilatory effects: It activates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), increasing blood flow, oxygen, and growth factor delivery to the hair follicle.[2]Alhayaza, G., Hakami, A., AlMarzouk, L.H., Al Qurashi, A.A., Alghamdi, G., Alharithy, R. (2023). Topical minoxidil reported hair discoloration: a cross-sectional study. Dermatology Reports. 16(1). … Continue reading

- Potassium channel activation: This prolongs the growth (anagen) phase and shortens the resting (telogen) phase.

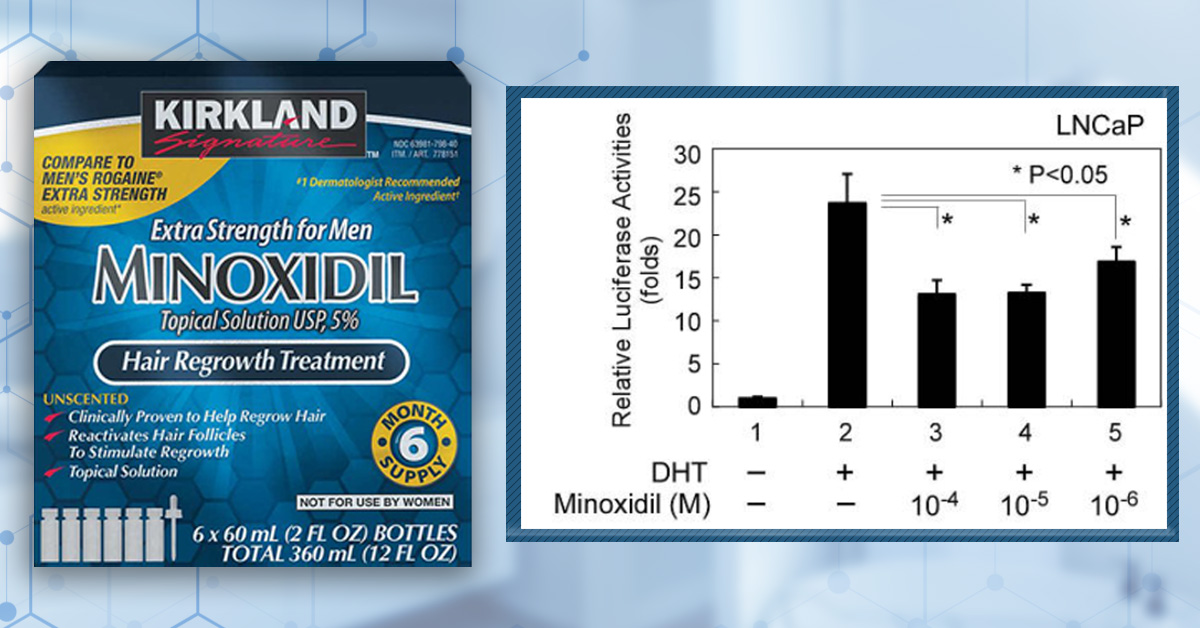

Research also shows that minoxidil can act on androgenic receptors, suppressing the expression of the androgen receptor and CYP17A1 and boosting the activity of CYP19A1. This decreases the formation and binding of dihydrotestosterone and enhances the production of estradiol, which may also benefit those with AGA.[3]Shen, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhang, L., Sun, J., Xie, B., Zhang, H., Song, X. (2023). New Target for Minoxidil in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 17. 2537-2547. … Continue reading

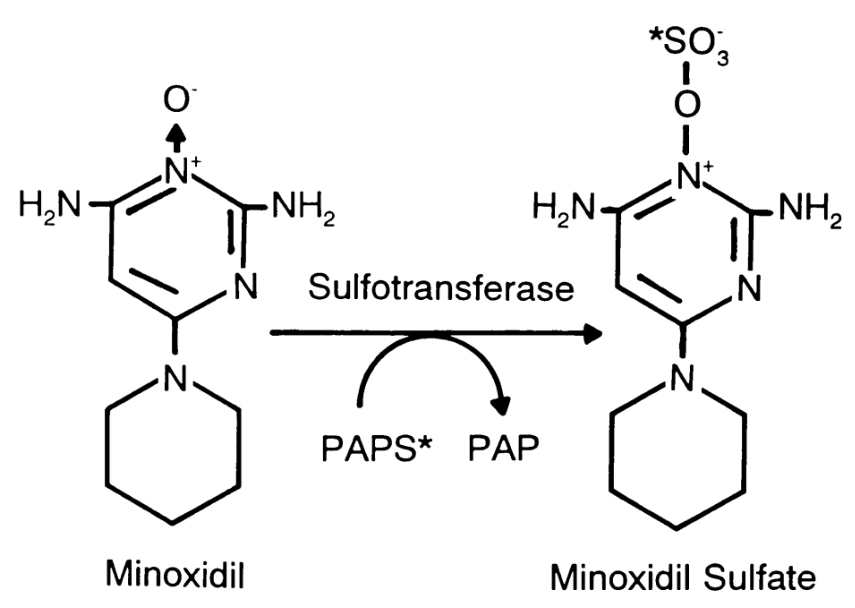

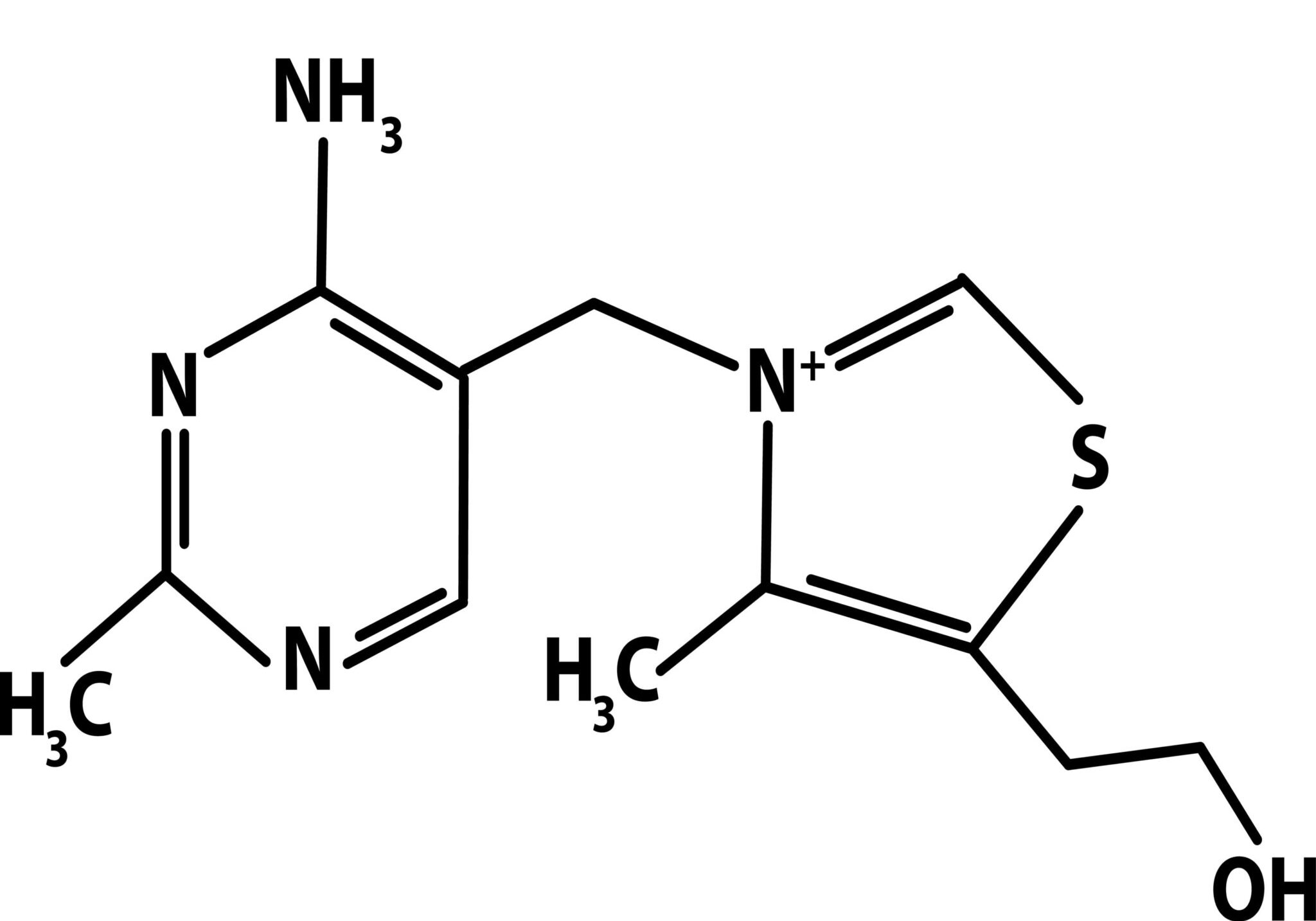

How is Minoxidil Activated in the Body?

Minoxidil needs to be converted into its active form, minoxidil sulfate, by sulfotransferase enzymes before it can effectively stimulate hair growth.[4]Dhurat, R., Daruwalla, S., Pai, S., Kovacevic, M., McCoy, J., Shapiro, J., Sinclair, R., Vano-Galvan, S., Goren, A. (2021). SULT1A1 (Minoxidil Sulfotransferase) enzyme booster significantly improves … Continue reading This conversion primarily occurs in the scalp for topical minoxidil and in the liver for oral minoxidil.

Figure 1: The conversion of minoxidil to minoxidil sulfate by sulfotransferase.[5]Anderson, R.J., Kudlacek, P.E., Clemens, D.L. (1998). Sulfation of minoxidil by multiple human cytosolic sulfotransferases. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 109. 53-67. Available at: … Continue reading

However, enzyme activity varies significantly among individuals, meaning that some people naturally produce higher levels of sulfotransferase, allowing for better activation and increased effectiveness of the drug, while others have lower enzyme activity, which can limit its impact. You can read our article on how your genetics can influence sulfotransferase activity here.

Topical Minoxidil Vs. Oral Minoxidil: Activation Pathways

Topical minoxidil and oral minoxidil differ in application and effectiveness. Topical minoxidil is applied directly to the scalp, while oral minoxidil is taken as a pill.

The efficacy of these two treatment routes differs because of their distinct metabolic pathways.

Topical Minoxidil

Topical minoxidil is applied directly to the scalp, presenting a challenge for drug activation. The drug requires conversion to its active form, minoxidil sulfate, by sulfotransferase enzymes in the scalp. However, research has shown that 40-60% of people may lack sufficient enzyme levels to effectively activate the medication. This enzymatic variability means that for many users, topical minoxidil may not be 100% effective.

Around 1.4% of topical minoxidil is systemically absorbed, further limiting minoxidil efficacy. To counteract this limitation, researchers have explored combining minoxidil with treatments like microneedling or retinoic acid. It was found that with these combinations, minoxidil efficacy can significantly increase.[6]Lama, S.B.C., Pérez-González, L.A., Kosoglu, M.A., Dennis, R., Ortega-Quijano, D. (2024). Physical Treatments and Therapies for Androgenetic Alopecia. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 13(15). 4534. … Continue reading

Oral Minoxidil

Oral minoxidil, however, is metabolized in the liver, where sulfotransferase enzymes are abundant. The activated minoxidil sulfate then enters the bloodstream, where it reaches the hair follicle. Studies consistently demonstrate higher response rates for oral minoxidil compared to topical.[7]Gupta, A.K., Talukder, M., Venkataraman, M., Bamimore, M.A. (2022). Minoxidil: a comprehensive review. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 33(4). 1896-1906. Available at: … Continue reading However, because oral minoxidil involves systemic absorption, it comes with a broader potential for side effects.

What Are the Side Effects of Topical Minoxidil?

Common Side Effects

While topical minoxidil typically has a great safety profile, there are some side effects that people can experience.

Common side effects include:

- Scalp Irritation and Contact Dermatitis: Redness, itching, flaking, and burning sensations.

These are the most frequently reported side effects from minoxidil. One retrospective study found that 6.4% of men reported mainly irritant and allergic reactions to minoxidil.[8]Shadi, Z. (2023). Compliance to Topical Minoxidil and Reasons for Discontinuation among Patients with Androgenetic Alopecia. Dermatology and Therapy (Heidelb). 13(5). 1157-1169. Available at: … Continue reading These effects are typically due to an allergic reaction to propylene glycol rather than the minoxidil itself.[9]Lessmann, H., Schnuch, A., Geier, J., Uter, W. (2005). Skin-sensitizing and irritant properties of propylene glycol. Contact Dermatitis. 53(5). 247-259. Available at: … Continue reading

To mitigate the negative skin effects of topical minoxidil, you can do several things. Starting with a lower concentration, such as 2% instead of 5%, can reduce the risk of irritation while still providing benefits. Additionally, reducing application frequency from twice to once daily can limit exposure. Switching to a foam-based minoxidil product can be particularly effective, as these formulations typically don’t contain propylene glycol, which is often responsible for uncomfortable side effects like irritation, redness, and scalp burning. Furthermore, incorporating a moisturizer into your scalp care routine can help keep the skin hydrated and comfortable, further alleviating potential irritation.

- Shedding Phase: Temporary increase in hair loss when starting treatment.

One study reported that 55% of topical minoxidil users experience minoxidil shedding.[10]Ghonemy, S., Bessar, H., Alarawi, A. (2019). Efficacy and safety of a new 10% topical minoxidil versus 5% topical minoxidil and placebo in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia: a trichoscopic … Continue reading This is considered a normal side effect and usually indicates that the treatment is working. The shedding phase typically begins 2 to 4 weeks after starting treatment and subsides within 6 to 8 weeks as the hair cycle normalizes. After a few months of continuous use, most users should start seeing visible new hair growth.[11]Kaiser, M., Abdin, R., Gaumond, S.I., Issa, T. N., Jiminez, J.J. (2023). Treatment of androgenetic alopecia: current guidance and unmet needs. Clinical Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 16. … Continue reading

- Facial Hypertrichosis: Unwanted excess facial hair.

Women, especially those over 50 or with pre-existing facial hair, seem to be at higher risk of developing hypertrichosis from topical minoxidil use, and as with other side effects, it is more common when using the 5% than the 2% concentration.[12]Dawber, R.P.R, Rundegren, J. (2003). Hypertrichosis in females applying minoxidil topical solution and in normal controls. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 17(3). … Continue reading

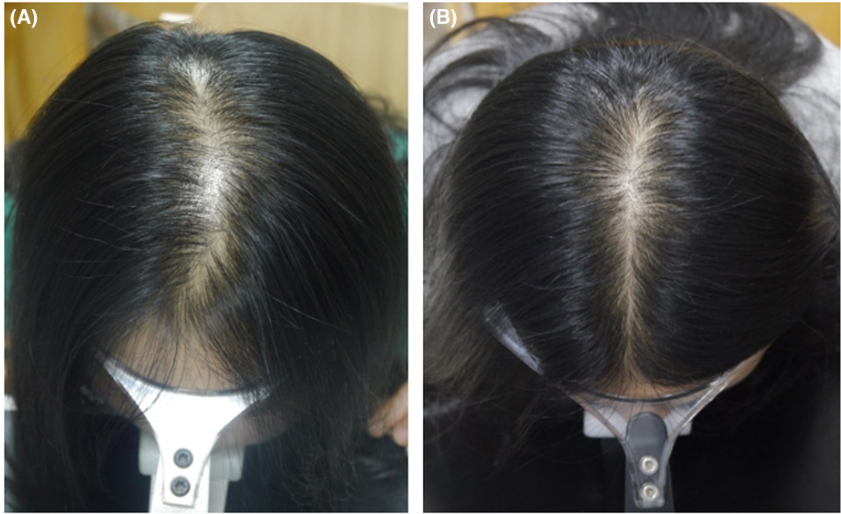

Figure 2: A 42 year old woman with generalized hypertrichosis after using 5% topical minoxidil for two weeks.[13]Gargallo V, Gutierrez C, Vanaclocha F, Guerra-Tapia A. Hipertricosis generalizada secundaria a minoxidil tópico. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:599–600. Available at: … Continue reading

There are several theories for why hypertrichosis occurs in people using topical minoxidil.

- Product application: The product wasn’t applied carefully enough or was not completely dried before bed, leading to product transfer from the pillow to the face. However, this doesn’t account for hypertrichosis seen away from the site of application and is unlikely to cause the effects seen in case studies.

- Percutaneous absorption: Although topical minoxidil is primarily intended for local effects, a small amount can be absorbed systemically through the skin. This can lead to circulating minoxidil reaching hair follicles in distant areas of the body.

- Follicular hypersensitivity: Some people may have hair follicles that are exceptionally responsive to minoxidil. In these cases, even minimal systemic exposure might be sufficient to stimulate hair growth in distant follicles. This hypersensitivity appears to occur randomly, depending on the person.

- Dose-dependent response: Higher concentrations are more likely to cause hypertrichosis.

While hypertrichosis can occur, it is generally reversible once minoxidil treatment is stopped and typically resolves within 3-4 months.

There are a number of ways that hypertrichosis can be avoided or treated once it occurs.

Starting with a lower concentration can reduce the risk, especially for women and those with a history of excess facial hair. Careful application to the scalp only, allowing proper drying time, and adhering to the recommended dosage can also minimize systemic absorption and unintended spread.

Switching to a foam version may help those experiencing side effects. If you are experiencing mild hypertrichosis and don’t want to stop using minoxidil, you could use hair removal methods while continuing treatment.

For more severe cases, spironolactone (~25 mg daily) ando/or low-dose bicalutamide (~10 mg daily) have shown promise in managing minoxidil-induced hypertrichosis. However, these medications should be used under medical supervision.[14]Darendeliler, F., Bas, F., Balaban, S., Bundak, R., Demirkol, D., Saka, N., Gunoz, H. (1996). Spironolactone therapy in hypertrichosis. European Journal of Endocrinology. 135(5).604-608. Available … Continue reading,[15]Moussa, A., Kazmi, A., Bakhari, L., Sinclair, R.D. (2022). Bicalutamide improves minoxidil-induced hypertrichosis in female pattern hair loss: a retrospective review of 35 patients. Journal of the … Continue reading

- Headaches

Some people also experience headaches after using topical minoxidil. One study found that in users applying 2% minoxidil solution, 0.6% reported headaches, compared to 3% of participants using 5% minoxidil solution.[16]Suchonwanit, P., Thammarucha, S., Leerunyakul, K. (2019). Minoxidil and its use in hair disorders: a review. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 13. 2777-2786. Available at: … Continue reading

Some people may simply experience headaches due to the smell of the product they are using, in which case, switching to an alcohol-free or unscented alternative may help. Others may be particularly sensitive to minoxidil and its vasodilatory effects, which might contribute to headaches. In this case, switching to a lower concentration or consulting with a healthcare provider might be preferable.

Some of our members have also switched to nanoxidil, an analogue of minoxidil that may offer a better safety profile (you can read more about the research quality of nanoxidil here), and found that their headaches resolved.

The above side effects are more often seen in the 5% than 2% solutions and are typically considered to be non-serious.[17]Nestor, M.S., Ablon, G., Gade, A., Han, H., Fischer, D.L. (2021). Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia: Efficacy, side effects, compliance, financial considerations, and ethics. Journal of … Continue reading

Some of the rarer side effects include:

- Water Retention

While less common than with oral minoxidil, topical minoxidil application can lead to water retention. Some topical minoxidil users have reported under-eye bags, which may be due to increased water retention near the application areas. There are also anecdotal reports of “puffy face” from topical minoxidil application, suggesting localized fluid retention.[18]Gungor, S., Kocaturk, E., Topal, I.O. (2015). Frontal Edema Due to Topical Application of %5 Minoxidil Solution Following Mesotherapy Injections. International Journal of Trichology. 7(2). 86-87. … Continue reading

Anecdotally, there have also been reports of swollen feet and weight gain from using topical minoxidil; however, we couldn’t find these reports reflected in peer-reviewed literature. These effects may also stop with continued use of the drug, so some people keep an eye on the symptoms and wait to see if they go away.

However, you can try reducing the concentration or frequency of usage if the symptoms continue longer than you are comfortable with. Furthermore, excessive salt intake can exacerbate symptoms of edema. Limiting salt intake may help you resolve the edema without having to stop using minoxidil.[19]Patel, P., Nessel, T.A., Kumar, D. (2023). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482378/ (Accessed: … Continue reading

- Cardiovascular Issues

Some people also experience cardiovascular side effects. One case study found that applying large amounts of 2% topical minoxidil led to hypotension (low blood pressure) and feelings of faintness.[20]Ponomareva, M.A., Romanova, M.A., Shapshnikova, A.A., Piavchenko, G.A. (2024). Topical Minoxidil Overdose in a Young Man with Androgenetic Alopecia: A Case Report. Cureus. 16(6). E62382. Available … Continue reading Another case also documented low blood pressure and fainting after applying 12.5% topical minoxidil daily.[21]Dubrey, S.W., vanGriethuysen, J., Edwards, C.M.B. A hairy fall: syncope resulting from topical application of minoxidil. BMJ Case Reports. 1-2. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-210945

Other people may experience heart palpitations, feelings of the heart beating rapidly or “skipping a beat”. While this is rare, one study found that 3.5% of women developed heart palpitations or a rapid heart rate after usage of 2% topical minoxidil solution compared to 1.8% who were using a 5% foam.[22]Blume-Peytavi, U., Hillmann, K., Dietz, E., Canfield, D., Bartels, N.G. (2011). A randomized, single-blind trial of 5% minoxidil foam once daily versus 2% minoxidil solution twice daily in the … Continue reading

Therefore, we would recommend seeking medical advice and potentially finding a new treatment for hair loss if you experience these side effects.

So we’ve covered the side effects of topical minoxidil, but what about oral?

What Are the Side Effects of Oral Minoxidil?

Oral minoxidil side effects are similar to those of topical minoxidil, and both forms exhibit dose-dependent effects. However, oral administration leads to significantly greater systemic exposure to the drug than topical application. As a result, oral minoxidil typically produces more pronounced hair regrowth and more pronounced systemic side effects. It should be noted that use of oral minoxidil to improve hair regrowth is an off-label use of the drug and it is not FDA-approved for this indication.

Common Side Effects

- Hair Shedding

Like with topical minoxidil, you may experience increased hair shedding when you start taking minoxidil. This is considered to be a normal part of the hair cycle remodeling process, typically beginning two to four weeks after starting treatment and subsiding within six to eight weeks as the hair cycle normalizes.

- Hypertrichosis

While rare with topical minoxidil use, one of the most frequently reported side effects of oral minoxidil is hypertrichosis, which involves excessive hair growth on various parts of the body. This effect is dose-dependent, with some studies showing that increasing the dosage of oral minoxidil by just 1 mg daily is associated with a 17.6% increased risk of hypertrichosis.[23]Gupta, A.K., Hall, D.C., Talukder, M., Bamimore, M.A. (2022). There is a Positive Dose-Dependent Association between Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil and Its Efficacy for Androgenetic Alopecia: Findings from … Continue reading

Hypertrichosis frequently occurs on the face (sideburns, temples, upper lip, and chin), with rarer cases of generalized hypertrichosis occurring over the whole body.[24]Desai, D.D., Nohria, A., Brinks, A., Needle, C., Shapiro, J., Lo Sicco, K.I. (2024). Minoxidil-induced hypertrichosis: Pathophysiology, clinical implications, and therapeutic strategies. JAAD … Continue reading

- Fluid Retention

Fluid retention is another common side effect of oral minoxidil, occurring in about 1.3% of patients.[25]Trueb, R.M., Caballero-Uribe, N., Luu, N.N.C., Dmitriev, A. (2022). Serious complication of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss. JAAD Case Reports. 30. 97-98. Available at: … Continue reading This can manifest as mild swelling in the face, hands, or feet. In some cases, it may lead to rapid weight gain.

This weight gain can be significant and sudden, with some patients experiencing up to 20 pounds of weight gain (as water weight) in as little as one month.[26]Patel.K., Omar, J. (2023). Low dose oral minoxidil causing peripheral edema and rapid weight gain. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 38(Suppl 3). S592. Available at: … Continue reading

Fluid retention can manifest in several ways:

- Peripheral edema: Swelling in the extremities, particularly in the legs, ankles, and feet.

- Facial swelling: Puffiness or swelling in the face.

- Overall weight gain: A sudden increase in body weight, often 5 pounds or more.

This rapid retention can be concerning for patients and may lead to additional health risks if left unmanaged. Excess fluid in the body can potentially lead to congestive heart failure if not properly addressed.

To mitigate these side effects, there are a number of options:

- Use of diuretics: Doctors can prescribe a diuretic (water pill) alongside minoxidil to help counteract fluid retention. This is typically a low-dose loop diuretic.

- Sodium restriction: Limiting sodium intake can help reduce fluid retention. Patients are often not advised about this when starting minoxidil, which can exacerbate the problem.

- Dose adjustment: If fluid retention becomes severe, temporarily discontinuing minoxidil or significantly reducing the dose may be necessary. This allows the edema to resolve naturally before restarting at a lower dose.

- Regular monitoring: Daily weight monitoring can help identify fluid retention early, making it easier to manage.

- Gradual titration: Slowly increasing the dose of minoxidil over time, rather than starting with 5 mg, can help minimize side effects.

If these symptoms don’t resolve when trying these strategies, then it’s recommended to visit your doctor and potentially stop taking minoxidil.

- Lightheadedness, Tachycardia (high heart rate), Headache and Insomnia

Oral minoxidil can cause several cardiovascular and neurological side effects, including lightheadedness, tachycardia, headache, and insomnia.[27]Trueb, R.M., Caballero-Uribe, N., Luu, N.N.C., Dmitriev, A. Serious complication of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss. JAAD Case Reports. 30. 97-98. Available at: … Continue reading These effects are generally dose-dependent and more common at higher doses.

Lightheadedness has been reported to occur in 1.7% of patients, tachycardia in 0.9%, headache in 0.4%, and insomnia in 0.2% of patients. These can all be symptoms of decreased blood pressure due to minoxidil’s vasodilatory properties.

Headaches and insomnia are reported in around 0.4% and 0.2% of patients, respectively, using low-dose oral minoxidil. While the exact mechanism of these side effects is not clear, it is thought that it could be related to the vasodilatory effects of the drug.

What Are The Cardiovascular Concerns of Oral Minoxidil Usage?

The severity and frequency of cardiovascular side effects are closely tied to the dosage of oral minoxidil. A meta-regression analysis found a positive dose-dependent correlation between low-dose oral minoxidil and the risk of cardiovascular adverse events.

Low Dose (0.25-1.25 mg/day)

At lower doses, oral minoxidil is generally well-tolerated. Women typically start with doses ≤ 1 mg, which minimizes the risk of significant side effects. Lower doses are considered to be a safer starting point for most patients, and even very low doses (0.25 mg/day) have shown efficacy in some studies.[28]Ramírez-Marín, H.A., Tosti, A. (2022). Role of oral minoxidil in patterned hair loss. Indian Dermatology Online Journal. 13(6). 729-733. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4103/idoj.idoj_246_22 If you are experiencing side effects at higher doses, you can reduce your dose at home using a pill cutter.

Moderate Dose (2.5-5 mg/day)

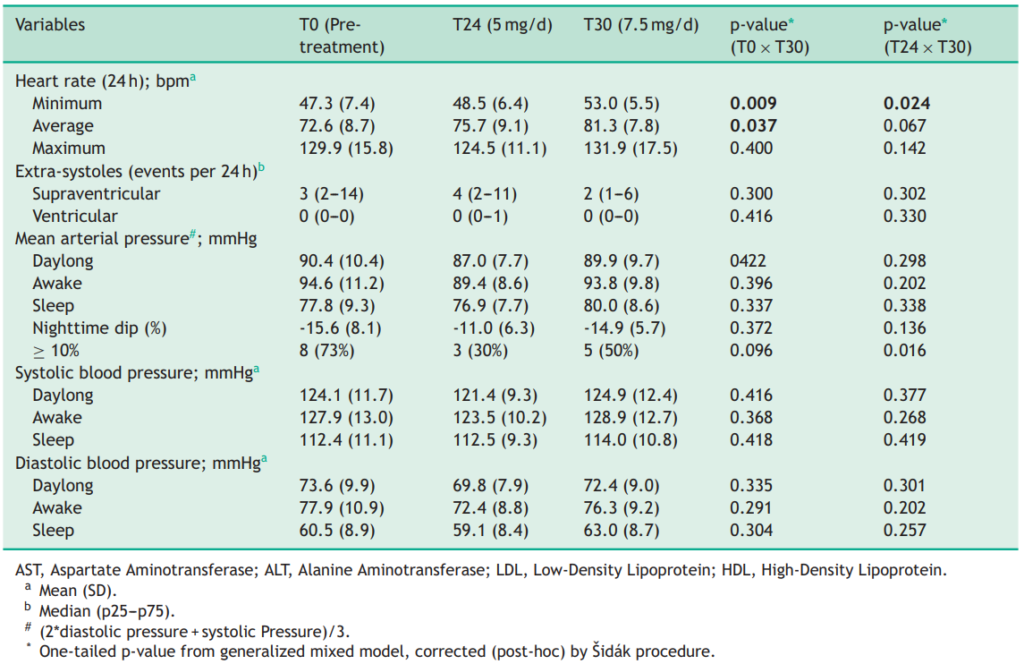

Men may be prescribed up to 5 mg of minoxidil daily, which can increase the likelihood of side effects such as dizziness and fluid retention. A recent study examined the effects of 7.5 mg/day oral minoxidil in patients with normal blood pressure and AGA.[29]Sanabria, B.D., Perdomo, Y.C., Miot, H.A., Ramos, P.M. (2024). Oral minoxidil 7.5 mg for hair loss increases heart rate with no change in blood pressure in 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. … Continue reading The results showed a mild increase in heart rate but no significant changes in blood pressure, suggesting that doses slightly higher than the typical 5 mg can be tolerated. However, this should only be considered under medical supervision.

Figure 3: Heart rate and blood pressure monitoring of 11 adult males with AGA after 24 weeks (T24) of treatment with 5 mg/day of oral minoxidil and after 6 weeks (T30) of treatment with 7.5 mg/day of oral minoxidil.[30]Sanabria, B.D., Perdomo, Y.C., Miot, H.A., Ramos, P.M. (2024). Oral minoxidil 7.5 mg for hair loss increases heart rate with no change in blood pressure in 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. … Continue reading

High Dose (10 mg/day and above)

Doses above 10 mg daily are associated with a higher risk of serious cardiac events and are typically not recommended for hair loss treatment. The hypotensive effect of oral minoxidil becomes more significant at these higher doses and is often prescribed alongside beta blockers and diuretics to manage the side effects.

How Can I Mitigate Oral Minoxidil Side Effects?

We have covered a number of ways to mitigate oral minoxidil side effects, but there are some further ways that you can adjust the use of minoxidil to reduce your risk.

Split-Dosing

Splitting the daily dosage of oral minoxidil into two administrations, one in the morning and one in the evening, can potentially optimize its efficacy while minimizing side effects. This approach is based on the pharmacokinetics of oral minoxidil, which has a relatively short half-life of approximately 3-4 hours.[31]Vano-Galvan, S., Pirmez, R., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Saceda-Corralo, D., Rodrigues-Barata, R., Jiminez-Cauhe, J., Koh, W.L., Poa, J.E., Jerjen, R., de Carvalho, L.T., John, J.M., … Continue reading

By dividing the total daily dose, you can maintain more consistent blood levels of minoxidil throughout the day, potentially leading to more stable hair growth stimulation. For example, if 5 mg is prescribed daily, taking 2.5 mg in the morning and 2.5 mg in the evening may be more beneficial than a single 5 mg dose.

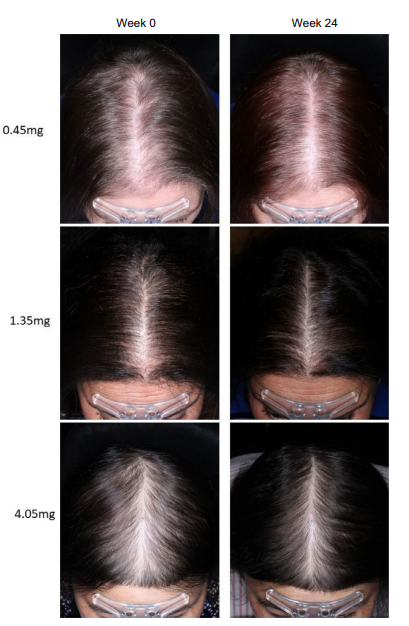

Sublingual Minoxidil

Some recommend using sublingual minoxidil as an alternative to traditional oral minoxidil. Sublingual administration involves a tablet that dissolves under the tongue. One 2021 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1b clinical trial investigated this delivery method.[32]Bokhari, L., Jones, L.N., Sinclair, R.D. (2021). Sublingual minoxidil for the treatment of male and female pattern hair loss: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1B clinical trial. … Continue reading The study tested daily doses of 0.45 mg to 4.05 mg of sublingual minoxidil.

This method offers several advantages:

- Bypasses first-pass metabolism in the liver.

- It allows for direct entry into the bloodstream, which can travel inactivated to the scalp and be activated by sulfotransferase at the site.

- Reduces systemic side effects.

- Improves bioavailability.

Key findings from the study included a dose-dependent improvement in hair parameters, with reduced side effects compared to oral minoxidil and no significant effect on blood pressure. In the blood, peak serum concentrations of minoxidil were only 10% of those seen with typical oral minoxidil.

Figure 4: Effect of different doses of sub-lingual minoxidil on hair regrowth outcomes after 24 weeks.[33]Bokhari, L., Jones, L.N., Sinclair, R.D. (2021). Sublingual minoxidil for the treatment of male and female pattern hair loss: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1B clinical trial. … Continue reading

At the 24-week follow-up, approximately 45% of patients in the 0.45 mg sublingual minoxidil group experienced improvements in frontal hair density, and 55% showed vertex improvement. Higher doses (4.05 mg) led to further results, with nearly 67% of patients experiencing improvements in both frontal and vertex hair density.

Sublingual minoxidil appears to be particularly beneficial for people concerned about the side effects of oral minoxidil. The medication was undetectable in plasma after 24 hours, and the mean peak minoxidil plasma concentration was significantly below the threshold associated with changes in blood pressure.

While the results are promising, it should be noted that this is the only study using sublingual minoxidil for AGA, and further studies with larger patient numbers are needed.

Switch To Topical Minoxidil

There is a chance that none of these options will work out for you, so you can try to switch to topical minoxidil. The side effects are more manageable for topical treatments, meaning that you can increase the dose and try to pair them with other treatments like microneedling or retinoic acid to further improve hair growth outcomes.

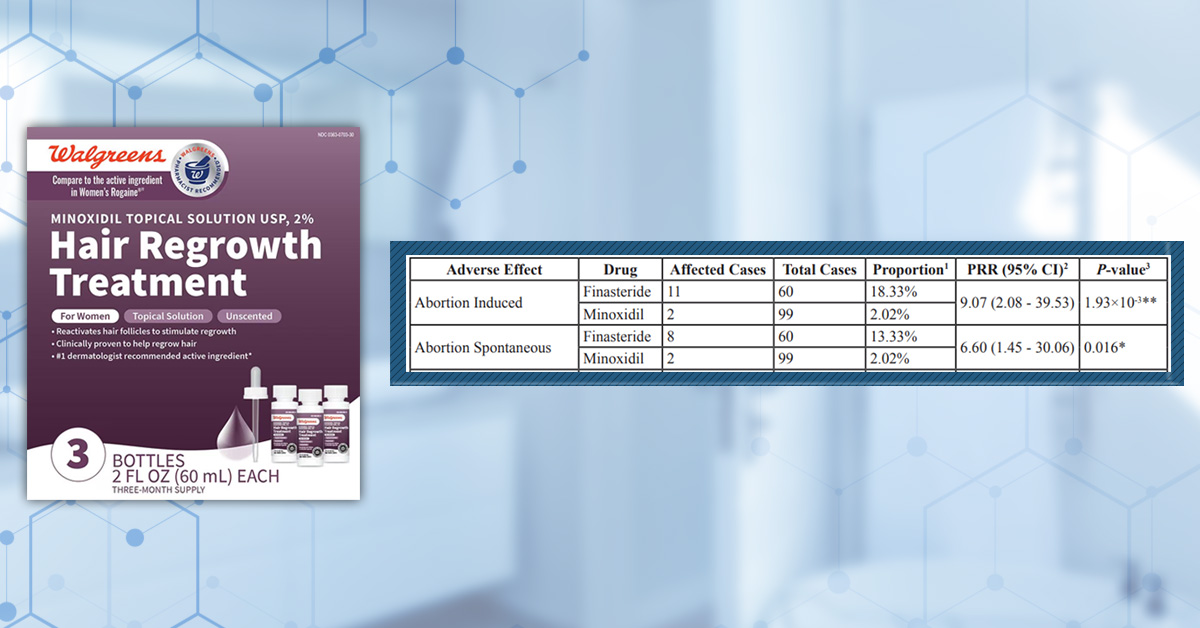

Can I Use Minoxidil If I Am Planning a Family?

Medical professionals generally advise against using both topical and oral minoxidil for both men and women when planning a family and for women during pregnancy and while breastfeeding.

While there is limited data on human pregnancies, animal studies have shown potential risks, including evidence of increased fetal resorption at high doses, one case report of fetal malformation associated with topical minoxidil use, and neonatal hypertrichosis reported following exposure during pregnancy.[34]Drugs. (2023). Minoxidil pregnancy and breastfeeding warnings. Drugs.com. Available at: https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/minoxidil.html (Accessed: February 2025),[35]Smorlesi, C., Caldarella, A., Caramelli, L., Di Lollo, S., Moroni, F. (2003). Topically applied minoxidil may cause fetal malformation: a case report. Birth defects research. Part A, Clinical and … Continue reading

There is a significant lack of well-controlled studies on minoxidil use during pregnancy and lactation. However, given the animal studies, medical professionals typically recommend avoiding minoxidil use when planning pregnancy, during pregnancy, and while breastfeeding, using adequate contraception if taking minoxidil, and discontinuing minoxidil use before attempting to conceive.[36]National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. (2021). Topical minoxidil. NICE. Available at: … Continue reading

Does Minoxidil Affect Male Fertility?

Current research suggests that minoxidil has minimal to no direct impact on male fertility. However, some research has linked minoxidil with oxidative stress and morphological changes to the testicles, which could indicate a potential negative impact.[37]Santana, F.F.V., Lozi, A.A., Goncalves, R.V., Silva, J.D., Matta, S.L.P.D. (2023). Comparative effects of finasteride and minoxidil on the male reproductive organs: A systematic review of in vitro … Continue reading

If you’re thinking about trying minoxidil and you are trying to conceive or have a pregnant partner, then it is advisable to talk to a medical professional before starting any treatment.

What if I’m Still Experiencing Side Effects?

Fortunately, minoxidil is just one of several treatment options available. If you’ve tried all of them and still experience side effects, you might consider exploring alternative therapies.

We have a wealth of information available so you can weigh your options and find out exactly how each treatment works and what your regrowth roadmap might look like. If you have any questions, reach out in the dedicated discussion thread below.

Final Thoughts

While minoxidil remains one of the most widely used treatments for AGA, both topical and oral formulations present unique challenges. The choice of which to use should be weighed carefully against the side effects, varying from mild scalp irritation to more significant cardiovascular effects. Ultimately, while the research supports minoxidil’s efficacy, it is not the only option out there, and if it isn’t working for you, then it is important to find the right one.

References[+]

References ↑1 Bryan, J. (2011). How minoxidil was transformed from an antihypertensive to hair-loss drug. The Pharmaceutical Journal. Available at: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/how-minoxidil-was-transformed-from-an-antihypertensive-to-hair-loss-drug#:~:text=DAMN%2DO%20was%20effective%20in,seen%20in%20canine%20toxicity%20studies.&text=Despite%20the%20adverse%20effects%2C%20demand,week%20limit%20on%20treatment%20duration.&text=Owing%20to%20the%20drug’s%20effectiveness,of%20hypertrichosis%20began%20to%20emerge. (Accessed: February 2025) ↑2 Alhayaza, G., Hakami, A., AlMarzouk, L.H., Al Qurashi, A.A., Alghamdi, G., Alharithy, R. (2023). Topical minoxidil reported hair discoloration: a cross-sectional study. Dermatology Reports. 16(1). 9745. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4081/dr.2023.9745 ↑3 Shen, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhang, L., Sun, J., Xie, B., Zhang, H., Song, X. (2023). New Target for Minoxidil in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 17. 2537-2547. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S427612 ↑4 Dhurat, R., Daruwalla, S., Pai, S., Kovacevic, M., McCoy, J., Shapiro, J., Sinclair, R., Vano-Galvan, S., Goren, A. (2021). SULT1A1 (Minoxidil Sulfotransferase) enzyme booster significantly improves response to topical minoxidil for hair growth. 21(1). 343-346. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14299 ↑5 Anderson, R.J., Kudlacek, P.E., Clemens, D.L. (1998). Sulfation of minoxidil by multiple human cytosolic sulfotransferases. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 109. 53-67. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00120-8 ↑6 Lama, S.B.C., Pérez-González, L.A., Kosoglu, M.A., Dennis, R., Ortega-Quijano, D. (2024). Physical Treatments and Therapies for Androgenetic Alopecia. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 13(15). 4534. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13154534 ↑7 Gupta, A.K., Talukder, M., Venkataraman, M., Bamimore, M.A. (2022). Minoxidil: a comprehensive review. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 33(4). 1896-1906. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2021.1945527 ↑8 Shadi, Z. (2023). Compliance to Topical Minoxidil and Reasons for Discontinuation among Patients with Androgenetic Alopecia. Dermatology and Therapy (Heidelb). 13(5). 1157-1169. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00919-x ↑9 Lessmann, H., Schnuch, A., Geier, J., Uter, W. (2005). Skin-sensitizing and irritant properties of propylene glycol. Contact Dermatitis. 53(5). 247-259. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.00693.x. ↑10 Ghonemy, S., Bessar, H., Alarawi, A. (2019). Efficacy and safety of a new 10% topical minoxidil versus 5% topical minoxidil and placebo in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia: a trichoscopic evaluation. Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 32(2). 236-241. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2019.1654070 ↑11 Kaiser, M., Abdin, R., Gaumond, S.I., Issa, T. N., Jiminez, J.J. (2023). Treatment of androgenetic alopecia: current guidance and unmet needs. Clinical Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 16. 1387-1406. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S385861 ↑12 Dawber, R.P.R, Rundegren, J. (2003). Hypertrichosis in females applying minoxidil topical solution and in normal controls. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 17(3). 271-275. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00621.x. ↑13 Gargallo V, Gutierrez C, Vanaclocha F, Guerra-Tapia A. Hipertricosis generalizada secundaria a minoxidil tópico. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:599–600. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adengl.2015.06.019 ↑14 Darendeliler, F., Bas, F., Balaban, S., Bundak, R., Demirkol, D., Saka, N., Gunoz, H. (1996). Spironolactone therapy in hypertrichosis. European Journal of Endocrinology. 135(5).604-608. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1530/eje.01350604 ↑15 Moussa, A., Kazmi, A., Bakhari, L., Sinclair, R.D. (2022). Bicalutamide improves minoxidil-induced hypertrichosis in female pattern hair loss: a retrospective review of 35 patients. Journal of the American Acadamy of Dermatology. 87(2). 488-490. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.048 ↑16 Suchonwanit, P., Thammarucha, S., Leerunyakul, K. (2019). Minoxidil and its use in hair disorders: a review. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 13. 2777-2786. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S214907 ↑17 Nestor, M.S., Ablon, G., Gade, A., Han, H., Fischer, D.L. (2021). Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia: Efficacy, side effects, compliance, financial considerations, and ethics. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 20. 3759-3781. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14537 ↑18 Gungor, S., Kocaturk, E., Topal, I.O. (2015). Frontal Edema Due to Topical Application of %5 Minoxidil Solution Following Mesotherapy Injections. International Journal of Trichology. 7(2). 86-87. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-7753.160124 ↑19 Patel, P., Nessel, T.A., Kumar, D. (2023). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482378/ (Accessed: February 2025) ↑20 Ponomareva, M.A., Romanova, M.A., Shapshnikova, A.A., Piavchenko, G.A. (2024). Topical Minoxidil Overdose in a Young Man with Androgenetic Alopecia: A Case Report. Cureus. 16(6). E62382. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.62382 ↑21 Dubrey, S.W., vanGriethuysen, J., Edwards, C.M.B. A hairy fall: syncope resulting from topical application of minoxidil. BMJ Case Reports. 1-2. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2015-210945 ↑22 Blume-Peytavi, U., Hillmann, K., Dietz, E., Canfield, D., Bartels, N.G. (2011). A randomized, single-blind trial of 5% minoxidil foam once daily versus 2% minoxidil solution twice daily in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in women. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 65(6). 1126-1134. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaas.2010.09.724 ↑23 Gupta, A.K., Hall, D.C., Talukder, M., Bamimore, M.A. (2022). There is a Positive Dose-Dependent Association between Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil and Its Efficacy for Androgenetic Alopecia: Findings from a Systematic Review with Meta-Regression Analyses. Skin Appendage Disorders. 8(5). 355-361. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1159/000525137 ↑24 Desai, D.D., Nohria, A., Brinks, A., Needle, C., Shapiro, J., Lo Sicco, K.I. (2024). Minoxidil-induced hypertrichosis: Pathophysiology, clinical implications, and therapeutic strategies. JAAD Reviews. 2. 41-49. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdrv.2024.08.002 ↑25 Trueb, R.M., Caballero-Uribe, N., Luu, N.N.C., Dmitriev, A. (2022). Serious complication of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss. JAAD Case Reports. 30. 97-98. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.09.035 ↑26 Patel.K., Omar, J. (2023). Low dose oral minoxidil causing peripheral edema and rapid weight gain. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 38(Suppl 3). S592. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.henryford.com/internalmedicine_mtgabstracts/162/ (Accessed: February 2024 ↑27 Trueb, R.M., Caballero-Uribe, N., Luu, N.N.C., Dmitriev, A. Serious complication of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss. JAAD Case Reports. 30. 97-98. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.09.035 ↑28 Ramírez-Marín, H.A., Tosti, A. (2022). Role of oral minoxidil in patterned hair loss. Indian Dermatology Online Journal. 13(6). 729-733. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4103/idoj.idoj_246_22 ↑29 Sanabria, B.D., Perdomo, Y.C., Miot, H.A., Ramos, P.M. (2024). Oral minoxidil 7.5 mg for hair loss increases heart rate with no change in blood pressure in 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 99(5). 734-736. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abd.2023.08.016 ↑30 Sanabria, B.D., Perdomo, Y.C., Miot, H.A., Ramos, P.M. (2024). Oral minoxidil 7.5 mg for hair loss increases heart rate with no change in blood pressure in 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 99(5). 734-736. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abd.2023.08.016 ↑31 Vano-Galvan, S., Pirmez, R., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Saceda-Corralo, D., Rodrigues-Barata, R., Jiminez-Cauhe, J., Koh, W.L., Poa, J.E., Jerjen, R., de Carvalho, L.T., John, J.M., Salas-Callo, C.I., Vincenzi, C., Yin, L., Lo-Sicco, K., Waskiel-Burnat, A., Starace, M., Zamorano, J.L., Jaen-Olasolo, P., Piraccini, B.M., Rudnicka, L., Shapiro, J., Tosti, A., Sinclair, R., Bhoyrul, B. (2021). Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: A multicenter study of 1404 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 84(6). 1644-1651. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054 ↑32 Bokhari, L., Jones, L.N., Sinclair, R.D. (2021). Sublingual minoxidil for the treatment of male and female pattern hair loss: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1B clinical trial. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. (36)1. E62-e66. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17623 ↑33 Bokhari, L., Jones, L.N., Sinclair, R.D. (2021). Sublingual minoxidil for the treatment of male and female pattern hair loss: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1B clinical trial. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. (36)1. E62-e66. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17623 ↑34 Drugs. (2023). Minoxidil pregnancy and breastfeeding warnings. Drugs.com. Available at: https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/minoxidil.html (Accessed: February 2025) ↑35 Smorlesi, C., Caldarella, A., Caramelli, L., Di Lollo, S., Moroni, F. (2003). Topically applied minoxidil may cause fetal malformation: a case report. Birth defects research. Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 67(12). 997-1001. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/bdra.10095 ↑36 National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. (2021). Topical minoxidil. NICE. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/female-pattern-hair-loss-female-androgenetic-alopecia/prescribing-information/topical-minoxidil/ (Accessed: February 2025) ↑37 Santana, F.F.V., Lozi, A.A., Goncalves, R.V., Silva, J.D., Matta, S.L.P.D. (2023). Comparative effects of finasteride and minoxidil on the male reproductive organs: A systematic review of in vitro and in vivo evidence. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 478. 11670. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2023.116710. Research continues to show that oral minoxidil is an effective off-label treatment for men with pattern hair loss. The general rule-of-thumb: the bigger the dose, the better hair regrowth. But there’s a catch…

Higher dosages of oral minoxidil come at a risk of higher risk of side effects: excessive body hair growth, limb swelling, low blood pressure, and even heart palpitations.

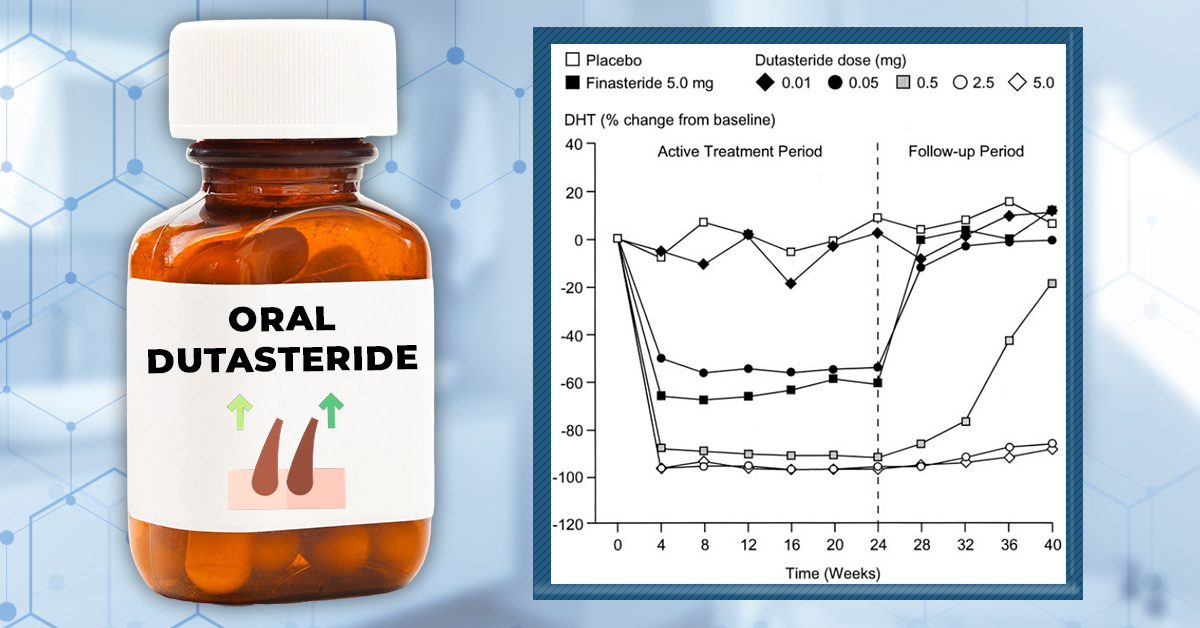

Knowing this, is there a “best dose” for oral minoxidil (in mg) for men with pattern hair loss? More specifically, which dose of oral minoxidil maximizes our chances for hair regrowth and minimizes our risks of adverse events?

This Quick Win uncovers the latest research. The short answer: studies show that 2.5mg daily seems to be a tolerable, effective dose for most men with pattern hair loss. But the right dose for you will depend on (1) your severity of hair loss, and (2) your tolerance with side effects (not all of them are bad).

Note: Quick Wins are short articles focused on answering one question about hair loss. Given their specificity, these articles are written in a more scientific tone. If you’re new to hair loss education, start with these articles.

Interested in Oral Minoxidil?

Low-dose oral minoxidil available, if prescribed*

Take the next step in your hair regrowth journey. Get started today with a provider who can prescribe a topical solution tailored for you.

*Only available in the U.S. Prescriptions not guaranteed. Restrictions apply. Off-label products are not endorsed by the FDA.

Oral minoxidil: research at a glance

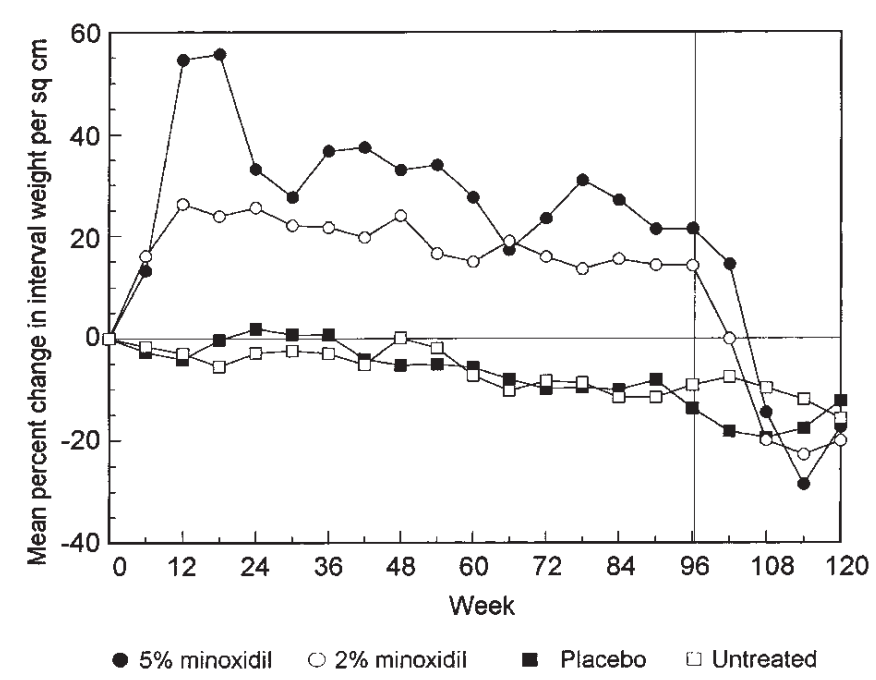

To date, there have been fewer than 10 studies published on oral minoxidil for androgenic alopecia (AGA). Doses studied range from 0.25mg to 5.0mg daily, and study durations (at least the ones we evaluated) range from 24-52 weeks.

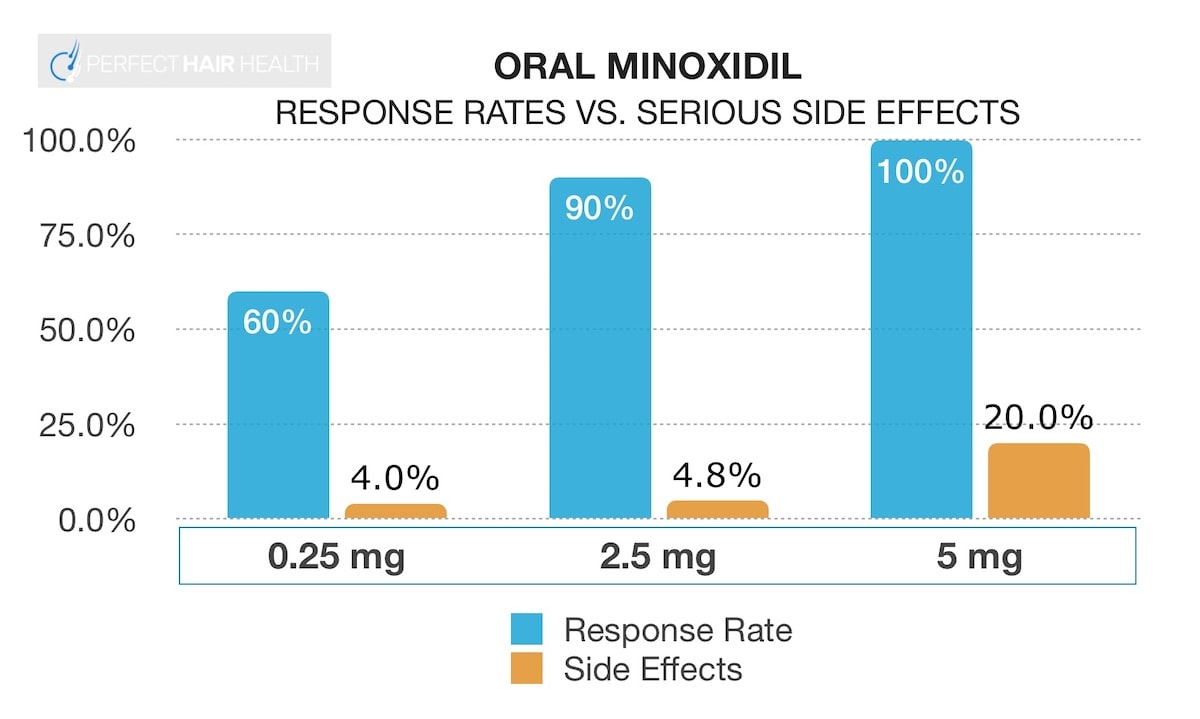

Across studies, there is a clear trend: the higher the dose of oral minoxidil, the better the hair regrowth. But this relationship doesn’t tell the whole story – as these higher dosages seem to confer with higher reports of side effects.

So, here’s what you should know before starting any daily dose of oral minoxidil.

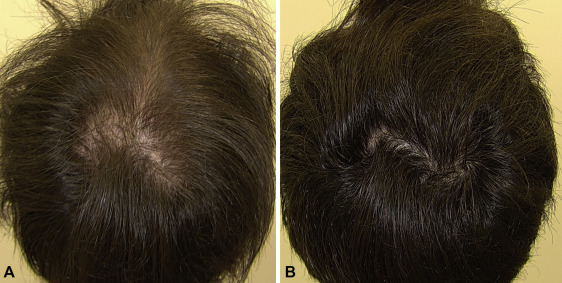

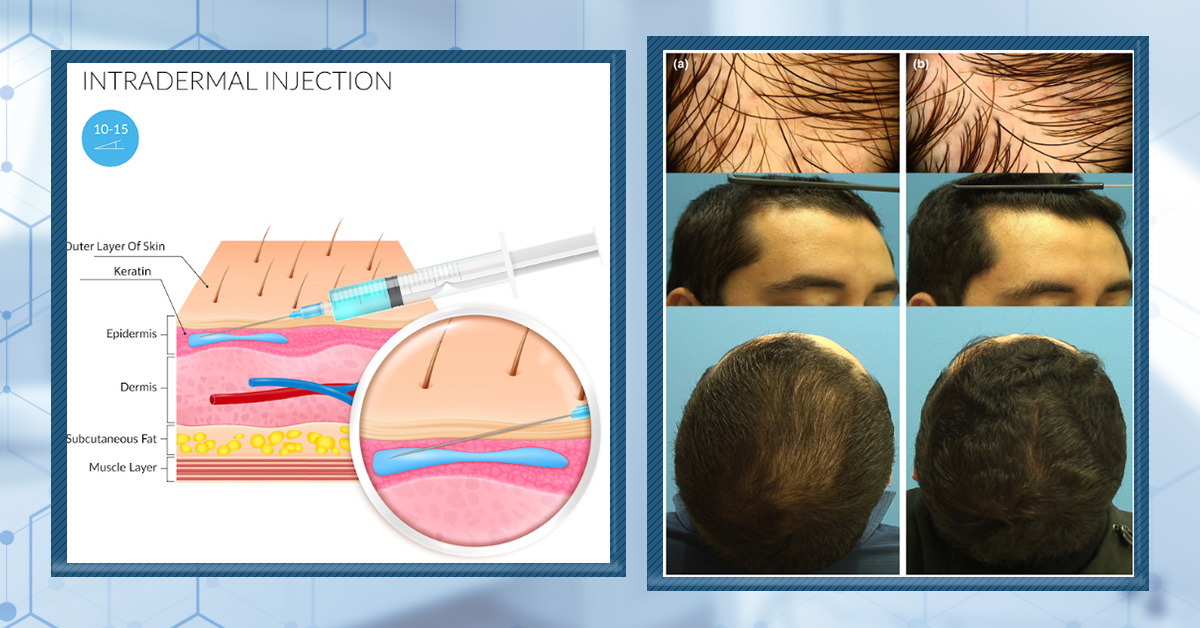

#1: Oral minoxidil dosages from 0.25mg to 5mg improve pattern hair loss

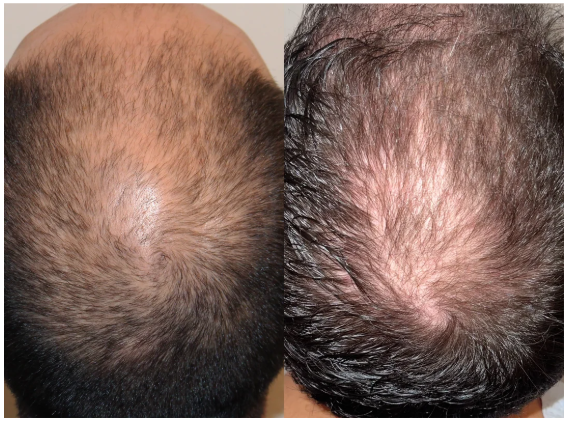

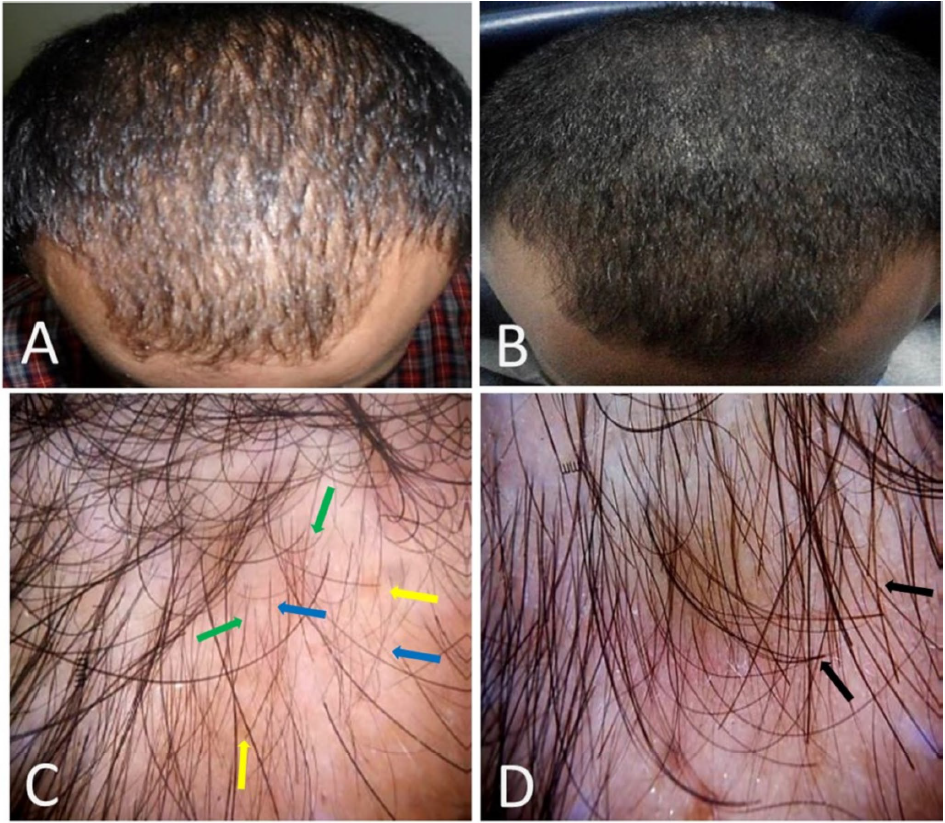

The three most recent (and most robust) studies on oral minoxidil all varied dosing by 0.25mg, 2.5mg, and 5.0mg daily. All of them showed benefit – with higher dosages demonstrating visual improvements. Just see these photos of a male who took 5mg of oral minoxidil daily for 3 months.[1]Jimenez-Cauhe, Juan et al. Effectiveness and safety of low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 81, Issue 2, 648 – 649

Male with AGA: improvement with 5mg oral minoxidil over 3 months

So, let’s organize the findings of these three studies by dosage. Then, let’s evaluate their results in terms of:

- Response rates (i.e., the percent of people who experienced an improvement), and…

- Side effects (i.e., unintended effects of the drug)

Do we see any trends in data? Specifically, is there a “sweet spot” where most men can maximize their chances of hair regrowth from oral minoxidil while minimizing their risk of serious side effects?

Yes.

Oral minoxidil for AGA: study results by dosage

See each study’s summaries.

Daily Dose (Duration)

Response Rate

Side Effects

0.25 mg

(6+ months)[2]Pirmez, Rodrigo et al. Very-low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia: A study with quantitative trichoscopic documentation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 82, … Continue reading60%

90%:

increased beard growth (52%), increased body hair (20%), hair shedding (16%), pedal edema (4%)2.5 mg to 5 mg

(6-12 months)[3]Jimenez-Cauhe, Juan et al. Effectiveness and safety of low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 81, Issue 2, 648 – 64990%

29.3%:

increased body hair (24.3%), lower limb edema (4.8%), hair shedding (2.4%)5 mg

(6 months)[4]Efficacy and safety of oral minoxidil 5 mg daily during 24-week treatment in male androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 72, Issue 5, AB113100%

100%:

increased body hair growth (93%), pedal edema (10%), heart / EKG alterations (10%)At first glance, the risk of side effects across even small dosages seems ridiculously high (90%+).

However, not all of these side effects are bad.

For instance, of the side effects reported in these studies, the overwhelming majority of them constituted increased body/facial hair growth. Most men aren’t going to care about this. In fact, man men might even prefer more body or facial hair.

Secondly, increased hair shedding was generally only reported at the beginning of each study. This is because, when starting minoxidil (topical or oral), the drug can “kickstart” a new anagen (growth) phase of hairs affected by androgenic alopecia (AGA). This can lead us to shed any hairs that were already primed to fall out soon anyway – specifically, catagen or telogen hairs – thereby giving the illusion of thinner hair in the first 1-2 months of treatment. However, as these hairs grow back, they’re usually much thicker, and thereby improve hair density. Long-story short: in most cases, hair shedding from minoxidil isn’t long-lived.

So, for this exercise, let’s discount increased body/facial hair growth and increased hair shedding as temporary and/or non-problematic side effects. Instead, let’s re-run our analysis and only consider serious side effects – edema, EKG alterations, etc.

Within this context, are all dosages of oral minoxidil as scary?

No. In fact, it seems like there’s a “sweet spot” for oral minoxidil where we can maximize hair regrowth while minimizing our risk of bad side effects: at 2.5mg daily.

Keep in mind the following chart is based on preliminary data on low-dose oral minoxidil, and that this article reflects the clinical studies available on oral minoxidil for androgenic alopecia as of 2020. As better-designed studies are published, these numbers will evolve:

Moreover, it’s really only at dosages of 5mg that we see an appreciable increase in concerning side effects – namely, edema (water retention / swelling) and cardiac alterations (i.e., lower heart rates).

So, 2.5 mg daily of oral minoxidil might be the “sweet spot” for most male pattern hair loss sufferers.

#2: Oral minoxidil’s efficacy may vary depending on hair loss severity

Most clinical trials on androgenic alopecia will select study participants who all have similar severities of hair loss. This is known as standardization. And for most trials, investigators usually prefer men who have medium-severity androgenic alopecia (i.e., Norwood 3-4). This is usually because men with Norwood 3-4 level hair loss (1) are representative of the population of hair loss sufferers who may later opt for this treatment, and (2) have enough hair follicle miniaturization and hair loss to effectively evaluate cosmetic improvements to hair thinning.

Having said that, most studies on oral minoxidil aren’t standardized to Norwood 3-4 participants. So, it’s a bit disingenuous to make comparisons across studies for response rates and side effects. In other words, please take our above analysis with a grain of salt.

With that said, with different age and/or hair loss severity across studies, we can get more granular data on who tends to respond well to oral minoxidil.

Based on the above studies (and others we looked into for our analysis), the trend aligned with intuition: if you don’t have severe hair loss, you can get away with lower dosages of oral minoxidil. If you do have severe hair loss, you’ll need a higher dose.

In other words:

- If you have mild male pattern baldness, 0.25mg daily might work fine as a starting point

- A more moderate case of hair loss might require a dose of 1-2.5mg daily

- If you have severe male pattern baldness, you’re probably going to need closer to 5mg daily

- If other treatments haven’t worked for you (resistant hair loss), you may also need a higher daily dose (2.5-5mg) or combination treatments with finasteride

Then again, higher doses come with more side effects. This is where dosing gets hyper-specific.

#3: If you’re going to try oral minoxidil, you’ll need to work with a doctor to figure out your unique risk profile and the right dose

Oral minoxidil is an antihypertensive drug (lowers blood pressure). It can also cause fluid retention. Therefore, if your health history indicates problems surrounding low blood pressure, fainting spells, or edema (swelling), you may be at a higher risk of complications from taking the drug.

Moreover, oral minoxidil can stimulate hair growth everywhere… not just on the scalp. For some men, this may be a bonus. For others, it might be a drawback. If this is a drawback for you, then it’s worth noting that reports of increased body / facial hair even occurred at lower dosages (0.25 mg) of oral minoxidil. So, if you’re concerned about this, maybe oral minoxidil isn’t right for you.

Long-tory short: for the safest and most effective use of oral minoxidil, discuss your medical history and preferences with your doctor. Then convince him or her to prescribe you oral minoxidil.

Note: a dermatologist specializing in hair loss is much more likely to write you a prescription. So, if you don’t want to waste any time, make a list of dermatologists in your area, call them to see if they’re open to prescribing oral minoxidil, and then only visit the ones who prescribe the drug.

#4: Like topical minoxidil, oral minoxidil likely works better alongside other treatments

When it comes to treating pattern hair loss, combination treatments tend to almost always outperform mono-treatments.

In some cases, combination therapies allow us to use the lowest dose of a drug possible without sacrificing results. Some studies suggest this is the case for women with pattern hair loss who take 0.25mg of oral minoxidil + 25mg of spironolactone: they minimize the risk of side effects of either drug while getting hair regrowth that often exceeds that of high dosages of either drug.

In other cases, combination therapies can actually enhance the efficacy of drugs. This tends to be true of men taking topical minoxidil, and who then add in once-weekly microneedling, thereby making topical minoxidil 400% more effective (according to some investigation groups). [5]English RS Jr, Ruiz S, DoAmaral P. Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022 Jan;12(1):41-60. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00653-2. Epub 2021 Dec … Continue reading

While there aren’t many studies that exhaustively explore this relationship for oral minoxidil, the odds are that this medication also works better as a combination therapy. So, if you’re going to commit to oral minoxidil, consider stacking it with other therapies.

Again, research here is limited, but there are a host of things you can try in combination with oral minoxidil that might increase results.

- DHT reducers (finasteride, saw palmetto, etc.)

- Microneedling

- Massage

- Ketoconazole shampoo

- Low-level laser therapy (LLLT)

- Platelet-rich plasma therapy (PRP)

…and more.

The bottom line

When it comes to oral minoxidil, the best daily dosage for men with pattern hair loss may vary depending on(1) your tolerance for certain side effects, and (2) your severity of hair loss. Consider these recommendations a mere starting point until more research emerges:

- Men with mild AGA, men at a higher risk of complication, or men who don’t want extra hair growth on their body/face: 0.25-1mg.

- Men with moderate AGA: 1-2.5mg.

- Men with resistant AGA (you’ve tried other treatments and they haven’t worked) or severe AGA: 2.5-5mg.

Although these guidelines are a rough ballpark, chances are you fit into one of these categories and, with the help of a doctor, can find the best oral minoxidil dosage for you.

Questions? Comments? Please reach out in the comments section.

References[+]

References ↑1, ↑3 Jimenez-Cauhe, Juan et al. Effectiveness and safety of low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 81, Issue 2, 648 – 649 ↑2 Pirmez, Rodrigo et al. Very-low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia: A study with quantitative trichoscopic documentation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 82, Issue 1, e21 – e22 ↑4 Efficacy and safety of oral minoxidil 5 mg daily during 24-week treatment in male androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Volume 72, Issue 5, AB113 ↑5 English RS Jr, Ruiz S, DoAmaral P. Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022 Jan;12(1):41-60. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00653-2. Epub 2021 Dec 1. PMID: 34854067; PMCID: PMC8776974. Vitamin B1 – also known as thiamin (or thiamine) – is part of the B-vitamin complex. Marketers claim that vitamin B1 can help support healthy hair growth, reduce hair shedding, and even prevent hair loss. Then again, marketers also make the same claims about B-vitamins like biotin, niacin, and vitamin B12. And typically, the claims are just plain wrong.

So, is vitamin B1 any different? In this article, we’ll dive into the evidence (and answers).

First, we’ll uncover why some people that vitamin B1 helps support hair growth. Then, we’ll dive into the evidence on the vitamin B1 / thiamin-hair loss connection. Finally, we’ll dive into evidence that might implicate vitamin B1 as an accelerator of hair loss… and steps to take if you suspect you’re deficient.

By the end, you’ll have a better idea of whether vitamin B1 is a worthy investment for your hair, or just another marketing gimmick. If you have any questions or comments, please post them below!

All-Natural Hair Supplement

The top natural ingredients for hair growth, all in one supplement.

Take the next step in your hair growth journey with a world-class natural supplement. Ingredients, doses, & concentrations built by science.

What is Vitamin B1?

Vitamin B1 (also thiamin or thiamine), is one of the many members of the B vitamin family.

Vitamin B1/thiamine

Researchers first identified this essential micronutrient through the study of beri beri, a serious disease of the nervous system that was common in South East Asia prior to the 1900s.

Unlike most diseases in that time, beri beri was much more common among wealthy citizens than it was among poorer citizens. Upon further investigation, researchers found the reason for the perplexing discrepancy was actually attributed to the differences in rice consumption.

While poorer individuals tended to consume brown rice, richer individuals tended to consume milled white rice — devoid of the husks, bran, and germ.

Through experimentation with this brown rice, a Polish biochemist, Casmir Funk, was able to isolate the compound that prevented beri beri. This compound? He termed it thiamine, meaning sulfur-containing amine — what we now know as vitamin B1.

Fast forward to today: we now know that vitamin B1 plays a crucial role in mitochondrial health, metabolism of macronutrients, and energy production — processes that are essential for the normal functioning of almost every cell in the body (1).

But, beyond the prevention of serious neurological conditions, does vitamin B1 have any benefit to our hair?

Let’s explore the evidence.

Vitamin B1: might it help support hair growth?

There’s no doubt that vitamin B1 is critical for important processes, like (1):

- The production of ATP, the energy molecule that fuels cellular activity

- The synthesis of amino acids

- The creation of NADPH, a co-factor necessary for steroid hormone production, fatty acid synthesis, and more.

And similar to other B-complex vitamins, vitamin B1’s role in these processes often form the basis of the claim that vitamin B1 can influence hair loss. After all, if you can’t produce amino acids — the raw material our hair is actually made of — how can you grow hair?

But, is this actually true? Are there any other ways that B1 might influence our hair? And what does this mean in the context of diet in the developed world?

Let’s explore the evidence.

Does a thiamine / vitamin B1 deficiency cause hair loss?

Maybe. But this isn’t the right question to ask. Rather, we need to ask this question in two parts:

- Does a vitamin B1 deficiency cause hair loss?

- Does a vitamin B1 deficiency within realistic parameters cause hair loss?

Why would we do this? Because at the extremes, almost anything causes hair loss. For instance, a “water deficiency” can cause hair loss. If we don’t drink water, we die. If we’re dead, we can’t grow hair. But that doesn’t mean that drinking water will regrow our hair. It also doesn’t mean we should warn people that hair loss is a side effect of a water deficiency.

The truth is that these types of logic leaps are what marketers use to claim that deficiencies in selenium, vitamin E, and iodine can all cause hair loss. Yes, this is true – but only if our scope of deficiency includes the endpoints: malnourished poverty-stricken children, people with genetic disorders who can’t absorb these nutrients, and people with certain chronic conditions that make nutrient assimilation nearly impossible.

All this is to say that we should ask if a thiamine deficiency, in the absolutes, causes hair loss. But the better question is: does a thiamine / vitamin B1 deficiency within realistic parameters cause hair loss, too?

Let’s take these one-by-one.

1. Does a thiamine deficiency, at the extremes, cause hair loss?

Maybe (in rodent models).

This 1968 study (2) sought to determine what happens in mice fed a diet that rapidly induces a thiamine deficiency. After two and a half weeks, some mice began to experience rapid weight loss, followed by abnormal hair shedding. Soon thereafter, neurological function began to decline. After four weeks, the mice were confused and could barely walk – symptoms similar to those seen in humans with beri beri.

However, it was unclear if the hair loss was caused by the vitamin B1 deficiency or the rapid weight loss.

2. Does a thiamine deficiency, within realistic parameters, cause hair loss?

Probably not.

For starters, people with beri beri rarely reported hair shedding (even despite their rapid weight loss). Moreover, when we expand our scope to human studies, we haven’t found any hard evidence that causally links a vitamin B1 deficiency to hair loss.

We could close the case right there, and say the article is done. At the same time, the absence of evidence doesn’t always imply evidence of absence.

For instance, there’s always the possibility that vitamin B1 might exacerbate certain chronic conditions linked to hair loss, or certain disease states associated with shedding disorders.

In fact, we could assert that since a vitamin B1 deficiency can lead to rapid neurological decline and thereby weight loss, and because rapid weight loss can trigger excessive (but temporary) hair shedding, then vitamin B1 deficiencies might be indirectly related to hair loss. The deficiency causes the weight loss; the weight loss causes the hair loss.

But again, if you’re so deficient in vitamin B1 that you start losing weight, you’ve got bigger things to worry about than your hair (like rapid impending neurological deterioration).

So, do we see any other circumstances where vitamin B1 is indirectly linked to hair shedding or hair loss?

Potentially. We can find them by look at the role of vitamin B1 in the body, and then comparing this to how different types of hair loss actually develop.

Vitamin B1 deficiency may exacerbate autoimmunity

At present time, there have been several animal studies conducted to investigate a link between vitamin B1 and autoimmunity. In general, these studies have suggested that vitamin B1 deficiencies may exacerbate autoimmunity in certain autoimmune disorders – specifically, multiple sclerosis (3, 4). It stands to reason that improving vitamin B1 deficiency may also improve these autoimmune conditions.

So, how could these effects translate to hair loss?

There are several forms of hair loss that seem to be mediated by autoimmune processes. These include alopecia areata as well as some forms of scarring alopecia.

If thiamine deficiencies happened to exacerbate the autoimmune processes involved in these hair loss disorders, it’s possible that restoring thiamine levels could improve these conditions.

Again, there’s no evidence that vitamin B1 deficiency is related to these hair-related autoimmune conditions. And while all autoimmune conditions involve autoimmune processes, not all autoimmune conditions develop in the same way. Thus, we can’t necessarily extrapolate the results from the animal studies, which primarily looked at multiple sclerosis, to the autoimmune conditions that lead to hair loss.

There’s also another point to consider: the effects of certain compounds reflected in animal studies are also traditionally very difficult to extrapolate to humans. Take our rodent study from earlier: thiamin-deficient rodents developed weight loss, neurological decline, and hair loss; whereas humans with beri beri – a sign of a thiamin deficiency – typically only develop weight loss and neurological decline.

That leaves us with one last piece of evidence to consider when it comes to linking autoimmune hair loss to vitamin B1: a case series on three human patients with autoimmune thyroid conditions (5).

Vitamin B1, autoimmune thyroid disorders, and hair shedding: a possible connection?

Autoimmune conditions that affect the thyroid – like Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis – can have a domino effect on hair growth which is, in part, controlled by thyroid hormones. When these hormones get too high (i.e., Graves’ disease) or too low (i.e., Hashimoto’s thyroiditis), it can cause telogen effluvium – a form of diffuse hair shedding.

Interestingly, vitamin B1 might have relevance here, especially in the context of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

In one case series, doctors administered vitamin B1 to three patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. They hypothesized that vitamin B1 could help relieve one of the hallmark symptoms of low thyroid hormone: fatigue.

Amazingly, that’s exactly what vitamin B1 did. In just a few hours to a few days, administration of B1 drastically improved the patients’ fatigue.

But, this wasn’t because of a subsequent improvement in the underlying autoimmune condition.

Instead, the authors hypothesized that the autoimmune processes involved in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis may have resulted in a vitamin B1 deficiency, subsequently leading to a reduction in energy production and, thus, fatigue.

In other words, the vitamin B1 deficiency likely isn’t a contributor to the development of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Instead, vitamin B1 deficiency, in this case, is a consequence of the condition.

As such, we can’t expect vitamin B1 to actually improve Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or the hair loss that occurs as a result. Instead, vitamin B1 can only improve symptoms related to a vitamin B1 deficiency that may occur alongside the condition.

So, we’ve established that vitamin B1 may or may not improve autoimmune forms of hair loss. We’ve also ruled out vitamin B1 as a means to improve Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and the hair shedding that ensues as a result.

But, are there any other pathways by which B1 might influence hair loss? Maybe… and that leads us to point number two.

Vitamin B1 deficiency may impair glutathione synthesis

Glutathione is a sulfur-containing compound with powerful antioxidant activity. Unlike antioxidants we consume in our diet (like polyphenols in green tea, berries, and other health-promoting foods), glutathione is manufactured by our own cells from amino acids like cysteine, glycine, and glutamic acid. This process requires NADPH, which requires vitamin B1 (along with various other B vitamins) (6).

So, how does this relate to hair loss?

Glutathione deficiency is associated with many conditions including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, as well as autoimmune diseases (7). Some studies also show low glutathione is associated with androgenic alopecia (AGA) (8).

As an anti-inflammatory agent, it’s possible that glutathione deficiency could exacerbate the microinflammation in AGA follicles — a process that drives the hair loss observed in AGA (7, 9).

In this context, it’s possible that through a possible increase in glutathione, vitamin B1 could reduce inflammation in AGA and, thus, improve AGA.

But there’s a difference between possible and plausible. Yes, if we stretch our imagination, it’s possible that a vitamin B1 deficiency might decrease glutathione production, and that if enough of this occurs in balding hair follicle sites, this decrease might exacerbate inflammation in AGA.

Possible, yes. But plausible?

Probably not.

While B1 deficiency seems to be related to low glutathione levels, vitamin B1 deficiency is extremely rare amongst most of the population. So, in this context, vitamin B1 is probably not something that most AGA patients need to worry about.

In these cases, glutathione deficiency is more likely to be related to co-morbidities seen in AGA: conditions like diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease (all of which we know can deplete glutathione) (10).

So, while vitamin B1 deficiency could, technically, lead to or exacerbate a glutathione deficiency, it’s safe to say this is probably not the case for most AGA patients with low glutathione.

A quick recap

So far, we’ve established that B1 is an essential micronutrient. We’ve also established that in its complete absence, it can cause hair loss in rodents. Aside from that, it doesn’t appear that a vitamin B1 deficiency is a major driver of hair loss in humans.

The reason for this is three-fold:

- Vitamin B1 deficiency is extremely uncommon in the general hair loss population.

- In the rare cases where vitamin B1 levels are depleted and associated with hair loss, improving vitamin B1 levels only improves symptoms associated with vitamin B1 depletion. In other words, vitamin B1 improves nervous system abnormalities like fatigue but not the underlying conditions that lead to hair loss.

- When looking at the relationship between vitamin B1, glutathione, and AGA, it’s unlikely that vitamin B1 deficiency contributes to low glutathione levels that may exacerbate hair loss. Rather, low glutathione levels observed in some patients appear to be a consequence of some common co-morbidities associated with AGA.

So, that leads us to this conclusion: in the overwhelming majority of cases, vitamin B1 is not likely to confer any benefit in hair loss.

This leaves us with one last question worth asking before we close the books on the vitamin B1-hair health connection…

Could increasing vitamin B1 levels beyond normal levels have any negative effect on hair loss?

Maybe, maybe not. Let’s look at the research.

Why vitamin B1 might be bad for hair: the NADPH-DHT connection

Vitamin B1 is an essential cofactor in the production of the molecule, NADPH.

NADPH – or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate – is a cofactor for enzymatic reactions. In other words, it’s a molecule that helps kickstart processes in the body. Earlier we established that NADPH was crucial for glutathione production. But that’s not all that NADPH does. NADPH is also essential for the production of steroid hormones.

Specifically, NADPH is a key molecule of the enzymatic process that converts testosterone into dihydrotestosterone, or DHT. Without NADPH, the enzyme that performs this conversion cannot function (11).

So, what does this mean for hair?

If you’ve done any research into androgenic alopecia (AGA), you probably already know that DHT is a significant contributor to the development of pattern hair loss (12). As such, any increase in DHT conversion could potentially worsen or speed up the balding process.

But, this would require NADPH to increase beyond what’s considered “physiological” — or what’s considered normal. So, does vitamin B1 do this?

Probably not. But we just don’t know.

What we do know is that, oftentimes, enzymes that produce molecules like NADPH have negative feedback mechanisms in place. This means that when their end-products increase, the body automatically reduces the activity of the enzymes that produce them. The net product is no increase in production.

However, this isn’t always the case. In some cases, these negative feedback loops are dysfunctional.

So, it’s possible that vitamin B1 doesn’t increase NADPH beyond what’s considered normal. As such, it’s also possible that vitamin B1 has no impact on DHT levels. At the same time, it’s also possible that it could.

In either case, the solution is the same: leverage diet to ensure vitamin B1 sufficiency and address a vitamin B1 deficiency if it’s present — but don’t go overboard.

If we’re deficient in B1, what should we do?

It’s important to note that an overwhelming majority of individuals likely aren’t deficient in vitamin B1. But, that doesn’t mean it’s impossible. Of the small pool of individuals B1 deficiency seems to affect in the modern world, risk factors appear to be:

- Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (5)

- Gastric bypass surgery (13)

- Anorexia (13)

- Severe crash dieting (13)

- Marked impairments in nutrient absorption, as in severe inflammatory bowel disease (13)

- Alcoholism (13)

- Septic shock (14)

But, again, it’s important to underscore that, even in these cases, we shouldn’t expect vitamin B1 to regrow our hair. This is because a vitamin B1 insufficiency is highly likely to present alongside other contributors to hair loss – like low thyroid hormone, zinc deficiency, iron deficiency, and severe calorie deficit. So, an improvement in B1 levels alone isn’t going to override these other factors. If anything, the thiamine deficiency-hair loss connection is more association than it is causation.

In any case, maintaining sufficient vitamin B1 levels is essential for overall health. So, you should aim to hit the recommended daily intake (RDI) everyday.

The good news is that you’re probably already doing this without even thinking about it – especially with all of the B-complex fortified foods out there. And if you find yourself falling into any of the risk categories, it’s not hard to find a supplement containing thiamine; nearly every multivitamin includes it as an ingredient.

At the same time, there could be a small minority of B1 deficiencies that go undetected, as was the case with the case series of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients. So, if you find yourself with fatigue that isn’t responding to standard treatment for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, it may be worth discussing the possibility of vitamin B1 supplementation with your doctor.

Summary

Vitamin B1 is an essential vitamin. It ensures our body can effectively produce amino acids, glutathione, and other cofactors that are crucial for cellular function.

Deficiencies in vitamin B1 have been linked to weight loss, neurological decline, and hair loss in rodents. In humans, the evidence points more so toward neurological decline and weight loss than it does hair shedding. Having said that, a vitamin B1 deficiency might indirectly exacerbate hair loss through:

- Rapid weight loss

- Autoimmunity

- Glutathione impairment

But the bottom line is this: if your thiamine / vitamin B1 levels are low enough to associate with hair loss, you’ve got bigger problems than hair… like mental debilitation, neurological deterioration, and impending death.