- About

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Education.

Prioritize knowledge. Make better choices.

- Evidence.

Sort good studies from the bad.

- Regrowth.

Get bigger hair gains.

Team MembersPhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Rob English

Founder, researcher, & consumer advocate

- Research Team

Our team of PhD’s, researchers, & more

Editorial PolicyDiscover how we conduct our research.

ContactHave questions? Contact us.

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- — Jenna, 31, U.S.A.

I have attached my before and afters of my progress since joining this group...

- — Tom, 30, U.K.

I’m convinced I’ve recovered to probably the hairline I had 3 years ago. Super stoked…

- — Rabih, 30’s, U.S.A.

My friends actually told me, “Your hairline improved. Your hair looks thicker...

- — RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A.

I also feel my hair has a different texture to it now…

- — Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA

Firstly thank you for your work in this field. I am immensely grateful that...

- — Ben M., U.S.A

I just wanted to thank you for all your research, for introducing me to this method...

- — Raul, 50, Spain

To be honest I am having fun with all this and I still don’t know how much...

- — Lisa, 52, U.S.

I see a massive amount of regrowth that is all less than about 8 cm long...

Client Testimonials150+ member experiences.

Scroll Down

Popular Treatments- Treatments

Popular treatments. But do they work?

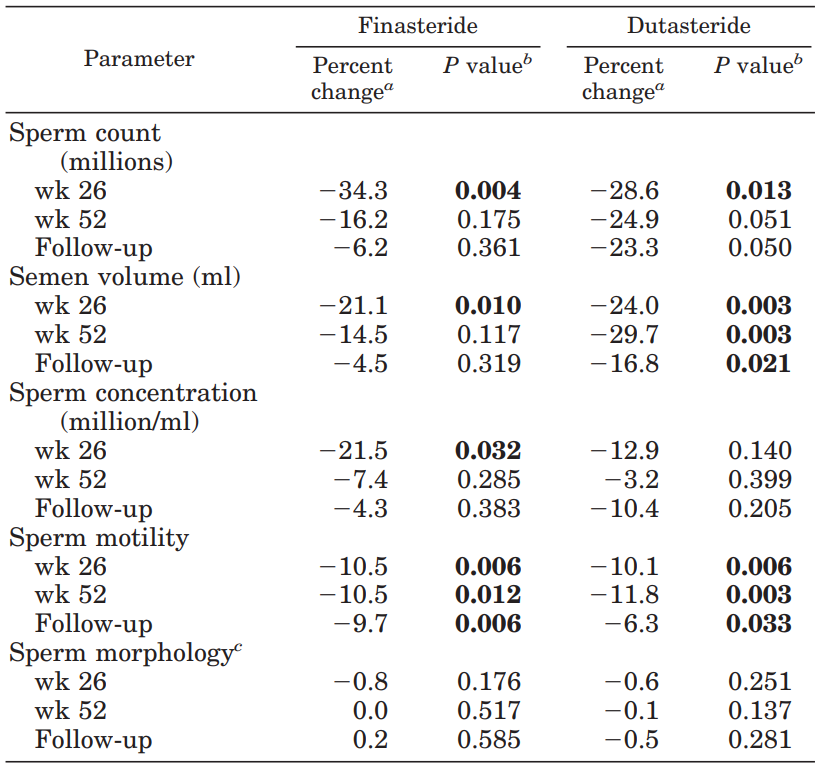

- Finasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Dutasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Mesotherapy

- Minoxidil

- Oral

- Topical

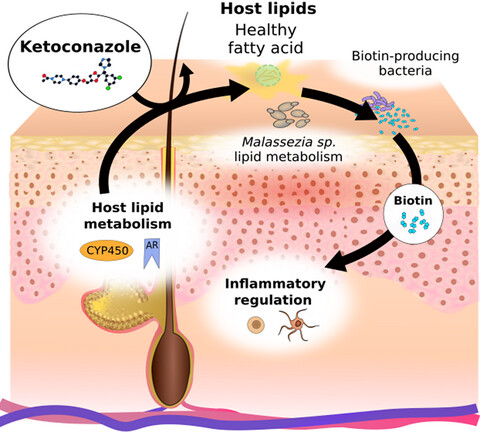

- Ketoconazole

- Shampoo

- Topical

- Low-Level Laser Therapy

- Therapy

- Microneedling

- Therapy

- Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy (PRP)

- Therapy

- Scalp Massages

- Therapy

More

IngredientsTop-selling ingredients, quantified.

- Saw Palmetto

- Redensyl

- Melatonin

- Caffeine

- Biotin

- Rosemary Oil

- Lilac Stem Cells

- Hydrolyzed Wheat Protein

- Sodium Lauryl Sulfate

More

ProductsThe truth about hair loss "best sellers".

- Minoxidil Tablets

Xyon Health

- Finasteride

Strut Health

- Hair Growth Supplements

Happy Head

- REVITA Tablets for Hair Growth Support

DS Laboratories

- FoliGROWTH Ultimate Hair Neutraceutical

Advanced Trichology

- Enhance Hair Density Serum

Fully Vital

- Topical Finasteride and Minoxidil

Xyon Health

- HairOmega Foaming Hair Growth Serum

DrFormulas

- Bio-Cleansing Shampoo

Revivogen MD

more

Key MetricsStandardized rubrics to evaluate all treatments.

- Evidence Quality

Is this treatment well studied?

- Regrowth Potential

How much regrowth can you expect?

- Long-Term Viability

Is this treatment safe & sustainable?

Free Research- Free Resources

Apps, tools, guides, freebies, & more.

- Free CalculatorTopical Finasteride Calculator

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: What Causes Hair Loss?

- Free ResourceFree Guide: Standardized Scalp Massages

- Free Course7-Day Hair Loss Email Course

- Free DatabaseIngredients Database

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: Hair Loss Disorders

- Free DatabaseTreatment Guides

- Free Lab TestsProduct Lab Tests: Purity & Potency

- Free Video & Write-upEvidence Quality Masterclass

- Free Interactive GuideDermatology Appointment Guide

More

Articles100+ free articles.

-

Hims Hair Growth Reviews: The Pros, Cons, and Real Results

-

Topical Finasteride Before and After: Real Case Studies

-

How to Reduce the Risk of Finasteride Side Effects

-

10 Best DHT-Blocking Shampoos

-

Best Minoxidil for Men: Top Picks for 2026

-

7 Best Oils for Hair Growth

-

Switching From Finasteride to Dutasteride

-

Best Minoxidil for Women: Top 6 Brands of 2026

PublicationsOur team’s peer-reviewed studies.

- Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review

- Use of Botulinum Toxin for Androgenic Alopecia: A Systematic Review

- Conflicting Reports Regarding the Histopathological Features of Androgenic Alopecia

- Self-Assessments of Standardized Scalp Massages for Androgenic Alopecia: Survey Results

- A Hypothetical Pathogenesis Model For Androgenic Alopecia:Clarifying The Dihydrotestosterone Paradox And Rate-Limiting Recovery Factors

Menu- AboutAbout

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Team Members

PhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Editorial Policy

Discover how we conduct our research.

- Contact

Have questions? Contact us.

- Before-Afters

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- Client Testimonials

Read the experiences of members

Before-Afters/ Client Testimonials- Popular Treatments

-

Articles

Oral minoxidil is an increasingly popular off-label treatment for hair loss, offering a convenient alternative to topical solutions for both men and women. Originally developed as a blood pressure medication, it was discovered to promote hair growth, sometimes dramatically, by enhancing blood flow and stimulating key pathways involved in hair growth.

In this article, we break down what oral minoxidil is, how it works, what the research reveals across different types of hair loss, potential side effects, and best practices for safe and effective use.

Key Takeaways:

- What is it? Oral minoxidil is a prescription vasodilator originally used to treat high blood pressure. At lower doses (0.25–5 mg daily), it’s increasingly prescribed off-label to treat hair loss, especially in people who don’t respond well to topical minoxidil. It promotes regrowth by enhancing blood flow, shortening the hair’s resting phase, and activating key follicular growth pathways.

- Clinical Data. Studies have shown that oral minoxidil is effective for multiple types of hair loss, including androgenic alopecia (AGA), chronic telogen effluvium, and even permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia. For AGA, it offers comparable or better results than 5% topical minoxidil, particularly at doses of 2.5–5 mg in men. In women, low-dose therapy (0.25–1.25 mg) is also effective, often combined with spironolactone for added benefit.

- Safety. At low doses, oral minoxidil is generally well-tolerated. The most common side effects include excess body hair, mild fluid retention, and lightheadedness. Rarely, serious cardiac issues like pericardial effusion may occur, especially in individuals with underlying health conditions. Most side effects are dose-dependent and reversible with adjustment or discontinuation.

- Evidence Quality. Oral minoxidil scored 63/100 for evidence quality by our metrics.

- Best Practices. Start with a low dose (2.5 mg for men, 0.25–1.25 mg for women) and titrate upward only if needed. Splitting doses between morning and night may improve tolerability. Sublingual minoxidil is a promising alternative to reduce systemic exposure. Combine with microneedling or topical agents if the results plateau. Always consult a healthcare provider, especially if you have concerns related to cardiovascular, renal, or hepatic health.

Interested in Oral Minoxidil?

Low-dose oral minoxidil available, if prescribed*

Take the next step in your hair regrowth journey. Get started today with a provider who can prescribe a topical solution tailored for you.

*Only available in the U.S. Prescriptions not guaranteed. Restrictions apply. Off-label products are not endorsed by the FDA.

What is Oral Minoxidil?

Oral minoxidil is a medication originally developed in the 1970s as an oral hypertensive agent, designed to lower high blood pressure by acting as a potent vasodilator. During its use for hypertension, clinicians observed a notable side effect: increased hair growth, or hypertrichosis.[1]Patel, P., Nessel, T.A., Kumar, D. (2023). Minoxidil. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/book/NBK482378/ Accessed: … Continue reading

This unexpected effect led to the development of topical minoxidil for hair loss, which was approved by the FDA in 1988 for male patients and in 1992 for female patients.[2]Nestor, M.S., Ablon, G., Gade, A., Han, H., Fischer, D.L. (2021). Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia: Efficacy, side effects, compliance, financial considerations, and ethics. Journal of … Continue reading Oral minoxidil is also used as an off-label treatment for both men and women.

Why Might I Consider Oral Over Topical Minoxidil?

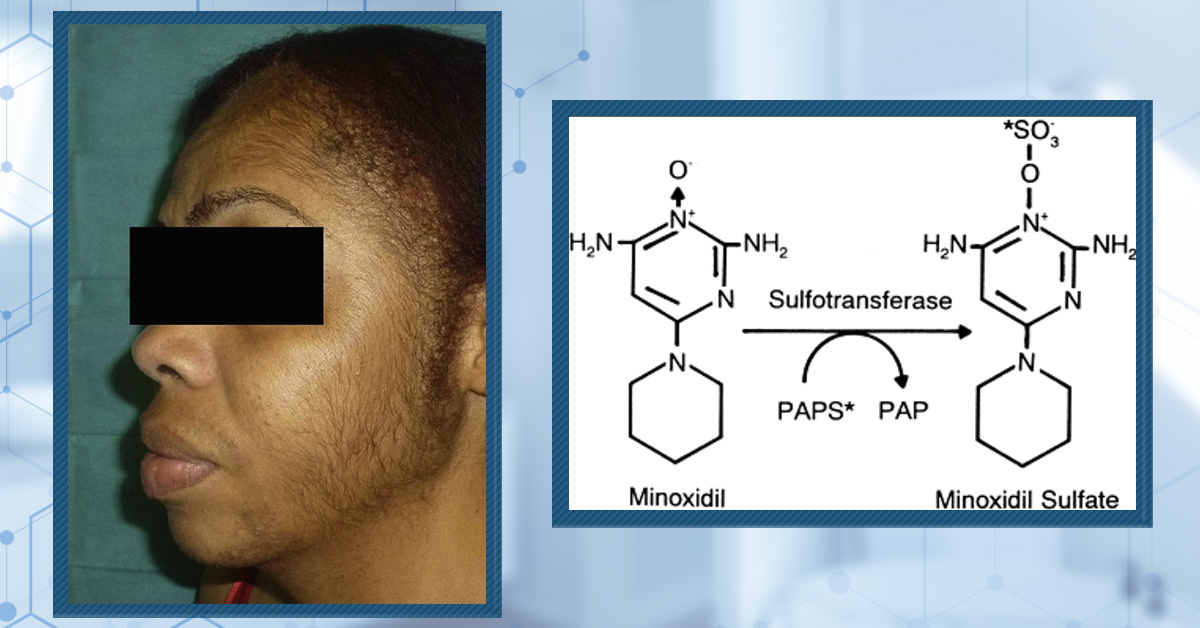

Many people consider oral minoxidil over topical due to fundamental differences in how each form is activated and delivered to hair follicles. Topical minoxidil is a pro-drug that requires conversion to its active form, minoxidil sulfate, by the sulfotransferase enzyme (specifically SULT1A1) located in the outer root sheath of scalp hair follicles.[3]Pietrauszka, K., Bergler-Czop, B. (2020). Sulfotransferase SULT1A1 activity in hair follicle, a prognostic marker of response to the minoxidil treatment in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a … Continue reading

However, the activity of this enzyme varies significantly between individuals. For example, in one study on 120 patients, 40.8% exhibited low levels of sulfotransferase activity in the scalp.[4]Chitalia, J., Dhurat, R., Goren, A., McCoy, J., Kovacevic, M., Situm, M., Naccarato, T., Lotti, T. (2018). Characterization of follicular minoxidil sulfotransferase activity in a cohort of pattern … Continue reading

Additionally, topical minoxidil faces a “penetration problem” where only about 1.4% of the drug applied is actually absorbed into the scalp skin under normal conditions.[5]Suchonwanit, P., Thammarucha, S., Leerunyakul, K. (2019). Minoxidil and its use in hair disorders: a review. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 13. 2777-2786. Available at: … Continue reading

Oral minoxidil largely bypasses these limitations. When taken by mouth, minoxidil is absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract and converted to its active form in the liver, where sulfotransferase activity is abundant. This ensures that nearly all ingested minoxidil is activated and delivered systemically, reaching hair follicles throughout the scalp and body, regardless of individual differences in scalp enzyme activity. As a result, oral minoxidil can be effective even for those who are non-responders to topical therapy due to low scalp sulfotransferase activity or poor drug penetration.[6]Beach, R.A. (2018). Case series of oral minoxidil for androgenetic and traction alopecia: Tolerability & the five C’s of oral therapy. Dermatologic Therapy. 31(6). E12707. Available at: … Continue reading

How Does Oral Minoxidil Work?

Oral minoxidil promotes hair growth through several interrelated mechanisms at the cellular and molecular levels.

Potassium Channel Activation and Vasodilation

Minoxidil is converted in the liver to its active form, minoxidil sulfate (first phase metabolism), which opens adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle and hair follicle cells.[7]Gupta, A.K., Talukder, M., Shemar, A., Priaccini, B.A., Tosti, A. (2023). Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil for Alopecia: A Comprehensive Review. Skin Appendage Disorders. 9(6). 423-437. Available at: … Continue reading

This action triggers a process known as membrane hyperpolarization, resulting in vasodilation and increased blood flow to the scalp. This increased microcirculation delivers more oxygen, nutrients, and growth factors to hair follicles, creating a favorable environment for hair growth.

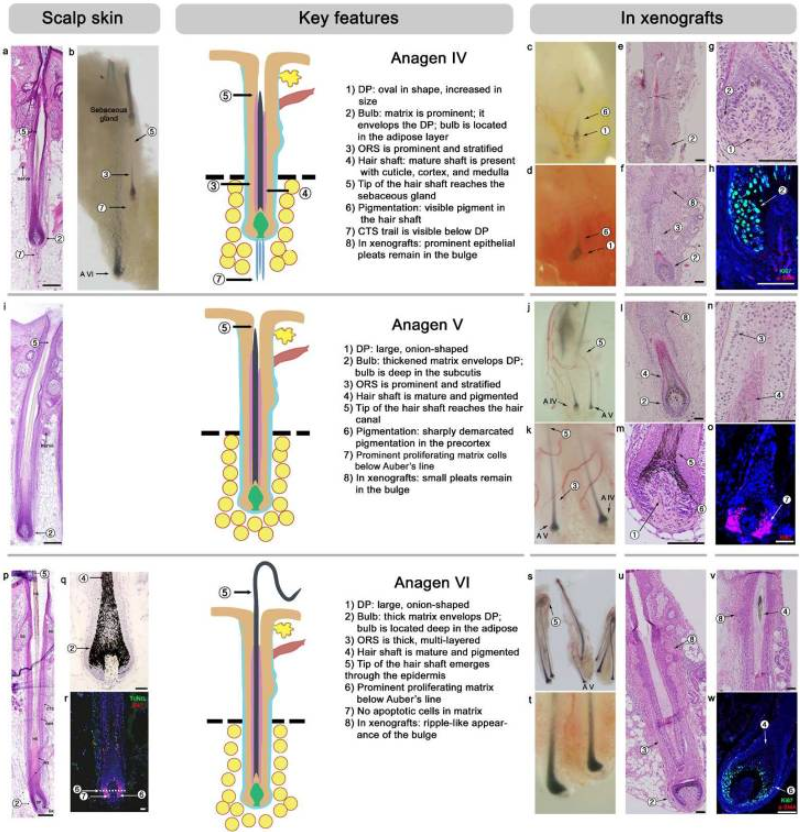

Stimulation of the Hair Growth Cycle

Minoxidil shortens the telogen (resting) phase and induces early entry of hair follicles into the anagen (growth) phase.[8]Suchonwanit, P., Thammarucha, S., Leerunyakul, K. (2019). Minoxidil and its use in hair loss disorders. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 13. 2777-2786. Available at: … Continue reading It also prolongs the duration of anagen, leading to longer and potentially thicker hair.

Activation of Wnt/ꞵ-Catenin Signaling

Minoxidil has been shown to activate the Wnt/ꞵ-Catenin pathway in dermal papilla cells. This pathway is a critical signaling route for hair follicle regeneration and maintenance of the anagen phase.[9]Kwack, M.H., Kang, B.M., Kim, M.K., Kim, J.C., Sung, Y.K. (2011). Minoxidil activates ꞵ-catenin pathway in human dermal papilla cells: a possible explanation for its anagen prolongation effect. … Continue reading It also promotes the growth and specialization of hair follicle stem cells, supporting follicle growth.[10]Wang, X., Liu, Y., He, J., Wang, J., Chen, X., Yang, R. (2022). Regulation of signaling pathways in hair follicle stem cells. Burns Trauma. 10. 1-19. Available at: … Continue reading

Direct Effects on Dermal Papilla Cells

Minoxidil stimulates the proliferation and survival of dermal papilla cells (DPCs), which are essential for hair follicle health.[11]Kang, J-I., Choi, K.Y., Han, S-C., Nam, H., Lee, G., Kang, J-H., Koh, Y.S., Hyun, J.W., Yoo, E.S., Kang, H.K. (2022). 5-Bromo-3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde Promotes Hair Growth through Activation of … Continue reading

It also activates the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and protein kinase B signaling pathways, increases the ratio of anti-apoptotic to pro-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2/Bax), and prevents cell death, thereby prolonging the anagen phase.[12]Jan, J.H., Kwon, O.S., Chung, J.H., Cho, K.H., Eun, H.C., Kim, K.H. (2004). Effect of minoxidil on proliferation and apoptosis in dermal papilla cells of human hair follicle. Journal of … Continue reading

Minoxidil also increases the expression of key growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which further support follicle nourishment and angiogenesis.[13]Nagai, N., Iwai, Y., Sakamoto, A., Otake, H., Oaku, Y., Abe, A., Nagahama, T. (2019). Drug Delivery System Based on Minoxidil Nanoparticles Promotes Hair Growth in C57BL/6 Mice. International Journal … Continue reading

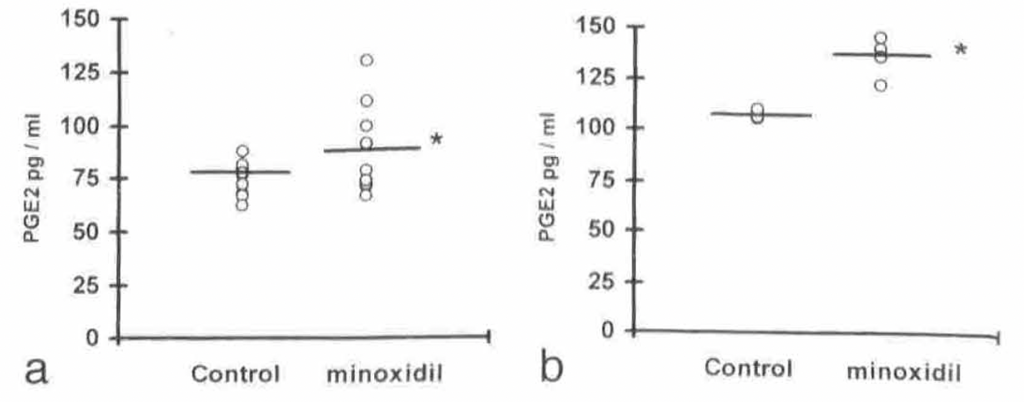

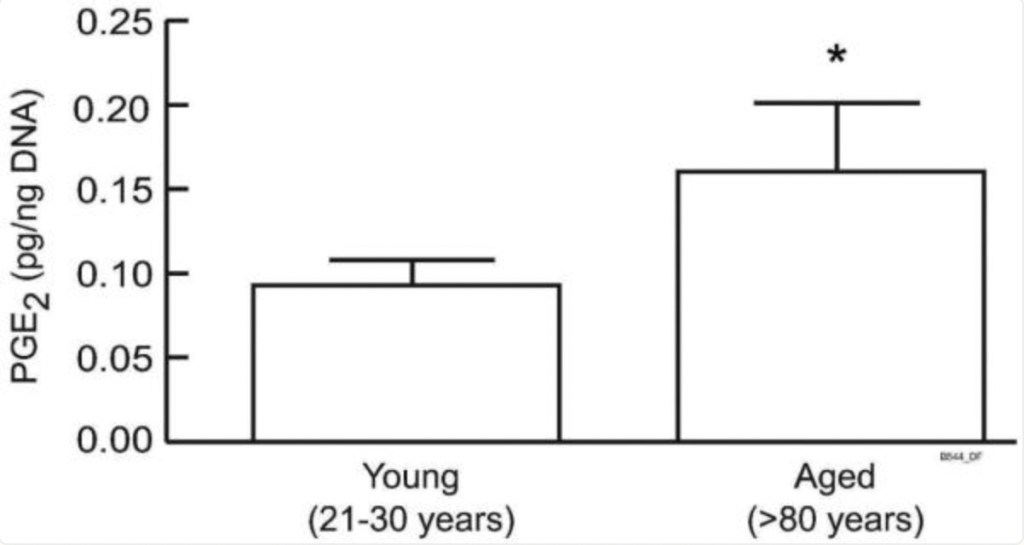

Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Fibrotic Properties

Minoxidil exhibits anti-inflammatory effects by modulating the production of prostaglandins and other inflammatory mediators.[14]Shin, D.W. (2022). The physiological and pharmacological roles of prostaglandins in hair growth. The Korean Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 26(6). 405-415. Available at: … Continue reading [15]Majewski, M., Gardas, K., Waskiel-Burnat, A., Ordak, M., Rudnicka, L. (2024). The Role of Minoxidil in Treatment of Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical … Continue reading It also inhibits collagen synthesis, which could reduce fibrosis around hair follicles, maintaining a healthy microenvironment for hair growth.[16]Fechine, C.O.C., Valente, N.Y.S., Romiti, R. (2022). Lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia: review and update of diagnostic and therapeutic features. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. … Continue reading

How Effective Is Oral Minoxidil?

Let’s break this down into the types of hair loss that minoxidil can assist with.

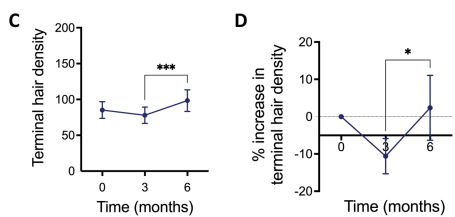

Pattern Hair Loss/Androgenic Alopecia (Females)

Oral minoxidil has been found to be as effective as 5% topical minoxidil at treating female pattern hair loss. The study found no significant difference between topical and oral minoxidil 1 mg daily in terms of efficacy for female pattern hair loss (FPHL).[17]Ramos, M.P., Sinclair, R.D., Kasprzak, M., Miot, H.A. (2020). Minoxidil 1 mg oral versus minoxidil 5% topical solution for the treatment of female-pattern hair loss. Journal of the American Academy … Continue reading There were, however, differences in the occurrence of adverse events. While scalp itching occurred only in the topical group, only users of oral minoxidil experienced excess hair growth outside of the scalp.

Another study combined low-dose minoxidil (0.25 mg) and 25 mg spironolactone to treat FPHL.[18]Sinclair, R.D. (2018). Female pattern hair loss: a pilot study investigating combination therapy with low-dose oral minoxidil and spironolactone. International Journal of Dermatology. 57(1). 104-109. … Continue reading The results of the study demonstrated that the combined therapy:

- Decreased hair shedding as early as 3 months into the treatment.

- Increased hair density after 6 months.

However, the authors didn’t report any objective measurements of hair density, either at baseline or at the end of the study period. This makes it impossible to effectively compare the results of the previously mentioned study with those of this study.

So, we can’t effectively assess the difference in efficacy of spironolactone and low-dose oral minoxidil combination therapy or oral minoxidil monotherapy. However, the authors of this study do note that they believe the combination has an added benefit for FPHL.

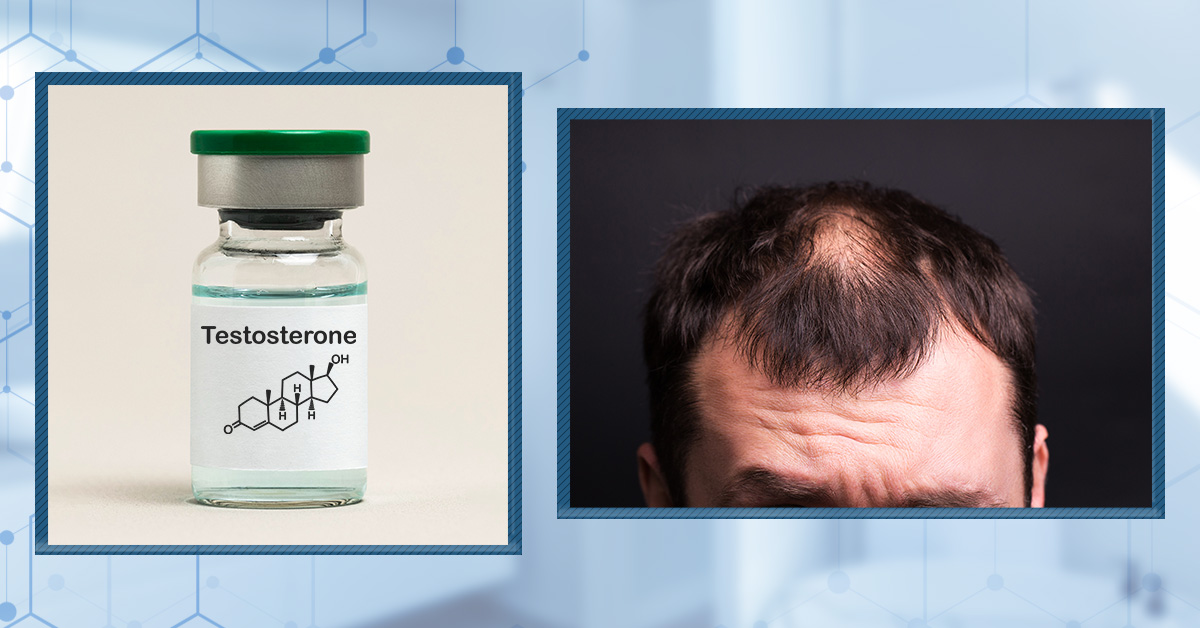

Pattern Hair Loss/Androgenic Alopecia (Males)

Of all forms of hair loss, AGA may derive the most benefit from minoxidil (whether oral or topical). This is because one of the main mechanisms of action directly addresses one of the pathological facets of AGA: reduced blood flow.

This is evidence in one study on men with AGA.[19]Lueangarun, S., Panchaprateep, R., Tempark, T., Noppakun, N. (2015). Efficacy and safety of oral minoxidil 5 mg daily during 24-week treatment in male androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the American … Continue reading In particular, it demonstrates a 100% response rate to a daily dose of 5 mg oral minoxidil. Even more impressively, subjects achieved an average 19% increase in hair count after 24 weeks.

The risk profile also appears to be favorable, with only 10% of participants reporting leg swelling. Ten percent of participants also reported a more significant side effect: an alteration in electrocardiogram (EKG) results.

These risks could theoretically be mitigated by lowering the dosage; however, one would need to consider the potential for reduced benefit. To better understand this, we’ll have to look at another study.

In line with the above results, this retrospective study showed a 90% response rate at 6-12 months for men taking 2.5-5.0 mg of oral minoxidil daily.[20]Jiminiez-Couche, J., Saceda-Corralo, D., Rodrigues-Barata, R., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Fernandez-Nieto, D., Vano-Galvan, S. (2019). Effectiveness and safety of low-dose oral … Continue reading Perhaps even more impressive is the fact that 60% of these men had tried other treatments for AGA, but had previously quit due to side effects or lack of efficacy.

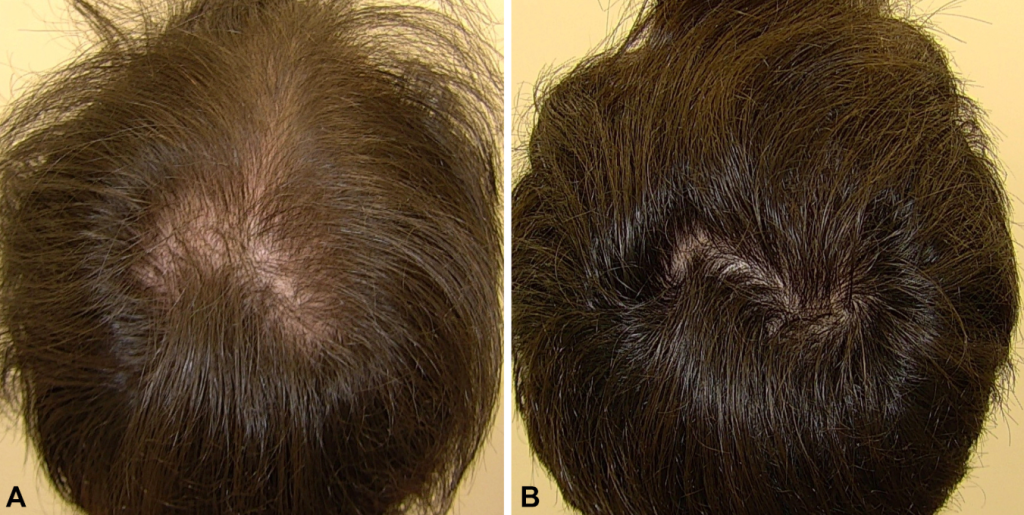

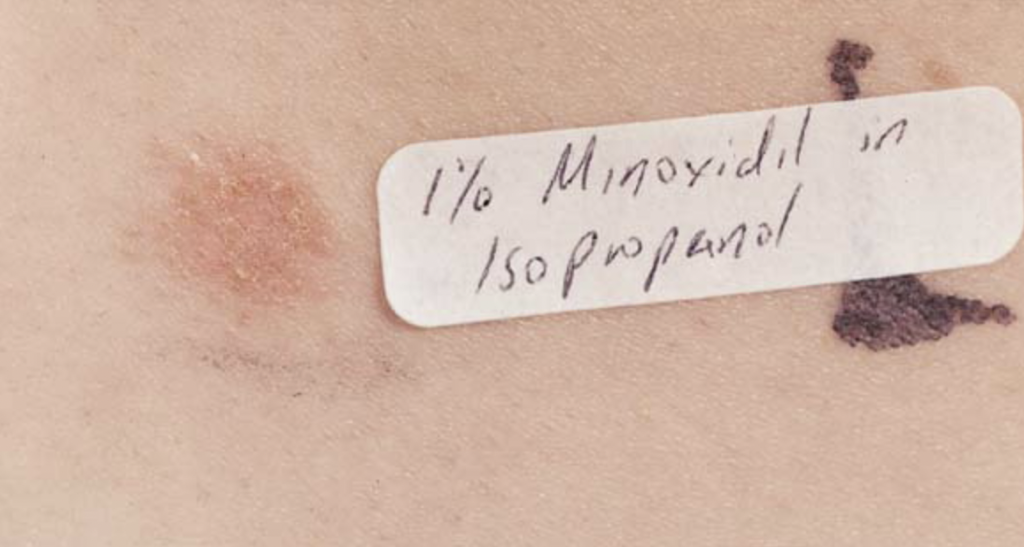

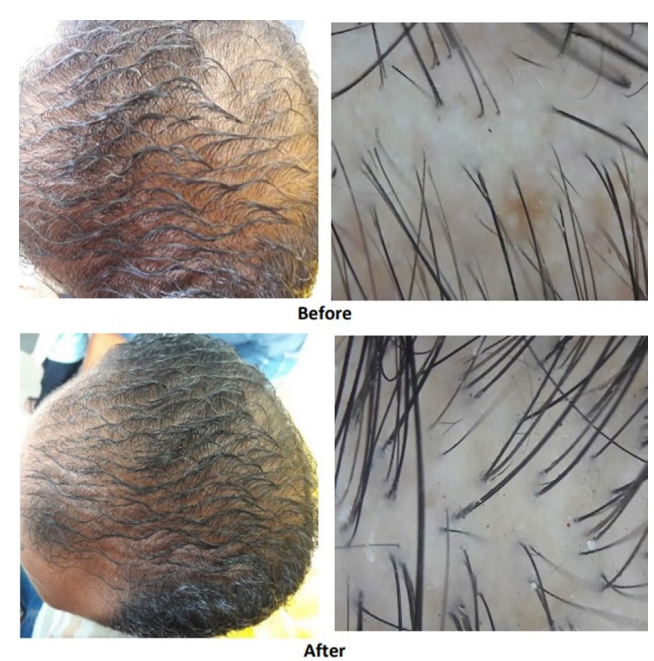

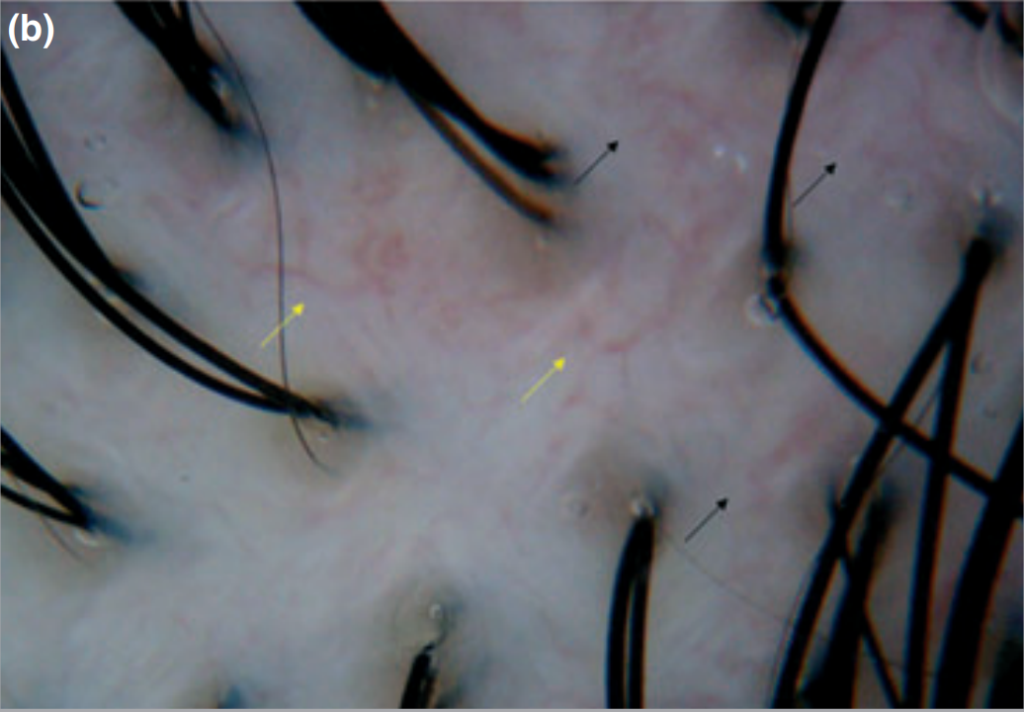

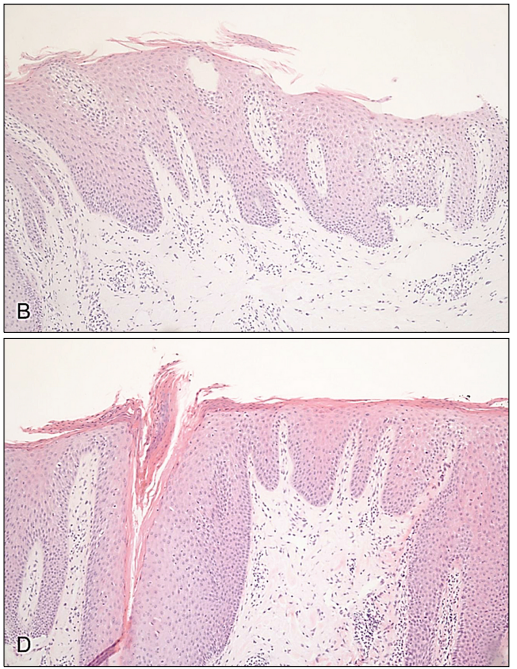

Figure 1: Male with AGA: Improvement with 5 mg oral minoxidil over 3 months.[21]Jiminiez-Couche, J., Saceda-Corralo, D., Rodrigues-Barata, R., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Fernandez-Nieto, D., Vano-Galvan, S. (2019). Effectiveness and safety of low-dose oral … Continue reading

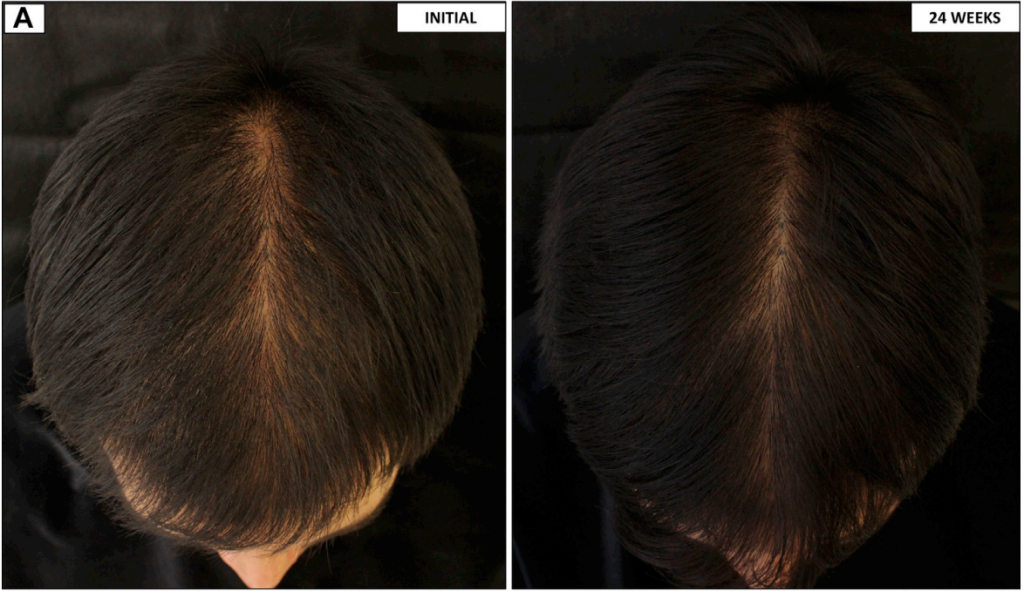

In line with the trend of “decreasing dosage, decreasing efficacy”, one study using 0.25 mg of oral minoxidil found a 60% response rate in male AGA patients.[22]Pirmez, R., Salas-Callo, C-I. (2020). Very-low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia: A study with quantitative trichoscopic documentation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. … Continue reading That’s on the low side for oral minoxidil overall, but on the high side when compared to topical minoxidil.

It’s also worth noting that there’s a key difference between this study and the one showing a 100% response rate at a 5mg daily dose. The 5mg study only included men with mild to moderate AGA; this study included both mild to moderate and severe AGA patients.

The mild to moderate group comprised 40% of study subjects, with the remaining 60% in the severe category. This suggests that low doses, such as 0.25mg, may be effective in severe AGA cases, at least in slowing and/or stopping their progression.

Figure 2: Pretreatment and post-treatment frontal region images of a 32-year-old man.[23]Pirmez, R., Salas-Callo, C-I. (2020). Very-low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia: A study with quantitative trichoscopic documentation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. … Continue reading

Notably, this study recorded leg swelling in only 4% of the group and found no difference in arterial pressure, suggesting that the risk of side effects reduces with decreasing dose. If these results were indeed confounded by the addition of severe AGA patients, these findings may indicate that 0.25 mg has a similar efficacy to 5 mg with a better risk profile.

All in all, it’s challenging to draw conclusions because the study designs differ significantly. In the future, it would be interesting to see how different groups with the same grade of AGA respond to 0.25 mg of minoxidil versus 5 mg of minoxidil. This could help us construct realistic treatment regimens that are both effective and minimize the risk of side effects.

Telogen Effluvium

Chronic telogen effluvium (CTE) is a common condition characterized by excessive hair shedding. Because one of minoxidil’s proposed mechanisms of action is its ability to shorten the “resting” telogen phase (where a lot of follicles stay in CTE, as opposed to the anagen growing phase), researchers have hypothesized that oral minoxidil may be a helpful treatment for the condition.

These hypothetical notions were explored in a recent 2017 study.[24]Perera, E., Sinclair, R. (2017). Treatment of chronic telogen effluvium with oral minoxidil: A retrospective study. F1000 Research. 6. 1650. Available at: … Continue reading This particular study was retrospective and looked at individuals with CTE who had been prescribed oral minoxidil (dosages ranging from 0.25 mg to 2.5 mg, with the most common being 1 mg) in-clinic.

They found that most patients experienced a decrease in hair loss after 6 months, with all patients showing an improvement either at the 6 or 12-month mark. This does not make minoxidil the be-all and end-all for CTE. The oral minoxidil treatment wasn’t compared against a placebo or any other potential treatments (including combination therapies) for the condition, so we can only conclude that topical minoxidil is one potential treatment for CTE.

We also need to acknowledge that most CTE cases may have an underlying cause that, when resolved, could improve hair shedding. In these cases, addressing the root cause of CTE, whenever possible, is far more effective.

Alopecia Areata

Upon investigation of topical minoxidil’s benefits for alopecia areata (AA), an autoimmune form of hair loss, researchers found that topical minoxidil, on its own, really doesn’t do much for alopecia areata (AA) patients.[25]Suchonwanit, P., Thammarucha, S., Leerunyakul, K. (2019). Minoxidil and its use in hair disorders: a review. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 13. 2777-2786. Available at: … Continue reading However, interestingly, oral minoxidil at a dose of 5 mg daily appears to be effective.

Although oral minoxidil for AA hasn’t been well-studied, one study reported that 18% of AA subjects taking oral minoxidil showed an improved cosmetic response after ~35 weeks of use.

Considering the side effects of oral minoxidil are increased at a dose of 5 mg, the 18% response rate doesn’t seem too promising. But there may be one combination therapy that proves to be more effective.

Another study found that adding oral minoxidil to a current alopecia areata treatment may enhance outcomes without increasing the current dosage.

Tofacitinib is an immunomodulator drug currently used to treat alopecia areata. Although the drug is usually effective for most individuals at a 10 mg daily dosage, some users may need to double the dose to see hair growth.[26]Wambier, C.G., Craiglow, B.G., King, B.A. (2021). Combination tofacitinib and oral minoxidil treatment for severe alopecia areata. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 85(3). 743-745. … Continue reading

While this usually resolves treatment resistance, increasing the dose may also increase the risk associated with strong immunomodulatory effects, as well as the cost. So, there’s a real need for safe combination therapies to improve treatment outcomes without increasing the tofacitinib dose.

Oral minoxidil may be able to do just this. One study demonstrated that daily addition of oral minoxidil (2.5 mg for women and 5 mg, split into 2.5 mg doses, for men) to doses of tofacitinib ranging from 10 mg to 20 mg daily resulted in:

- 67% of patients achieved 75% or greater hair regrowth, compared to another study’s results, which demonstrated that 20% of patients achieved cosmetically acceptable regrowth on oral minoxidil alone.

- The remaining 33% of patients experienced hair regrowth, with a range of 11% to 74%.

Chemotherapy-Induced Hair Loss

Permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia (PCIA), a hair-shedding disorder in which hair lost to chemotherapy does not grow back 6 months after the end of chemotherapy, is considered to be generally irreversible.

One case study challenges this.[27]Yang, X., Thai, K-E. (2016). Treatment of permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia with low-dose oral minoxidil. The Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 57(4). E120-e132. Available at: … Continue reading After one year of 1 mg daily oral minoxidil treatment, a woman with PCIA achieved considerable growth. This is pretty amazing, considering no consistently effective treatment has been found for PCIA patients, yet. While future studies are still needed to confirm these findings, these results are certainly promising.

Ultra-Low and Ultra-High Doses of Minoxidil

Recent Brazilian studies have been published showing efficacy from both low and high doses of minoxidil.

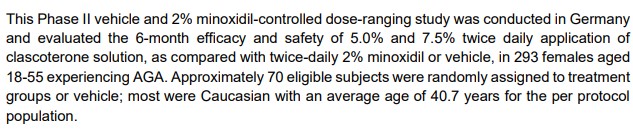

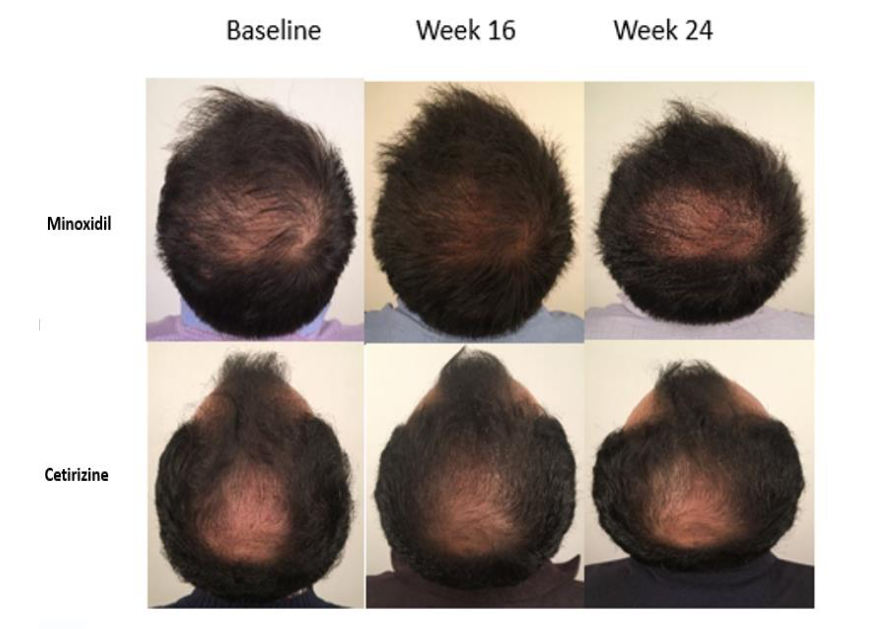

Low-Dose

One 2025 Brazilian double-blind, randomized clinical trial was conducted on 100 men aged 25-55 years with Norwood-Hamilton stage 3V to 5V AGA. The participants were randomized 1:1 to receive either 2.5 mg or 5 mg oral minoxidil daily for 24 weeks.[28]Varma, D. (2025). Oral Minoxidil 2.5 mg vs 5 mg: Similar Efficacy for Androgenetic Alopecia in Men. Medscape. Available at: … Continue reading,[29]Fonseca, L.P.C., Miot, H.A., Chaves, C.R.P., Ramos, P.M. (2025). Oral minoxidil 2.5 mg versus 5 mg for male androgenetic alopecia: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American … Continue reading

The primary outcome was the change in non-vellus hair density at the vertex. Secondary outcomes were total hair density changes, global photographic assessment, and adverse events.

At 24 weeks, there was no significant difference in non‑vellus hair density between the 2.5‑mg and 5‑mg groups (mean difference = 0.9 hairs/cm²; P = .403). Total hair density was likewise comparable (mean difference = 3.6 hairs/cm²; P = .078). Dermatologists assessing photographs in a blinded manner reported similar clinical improvement rates (64% with 2.5 mg vs 62% with 5 mg; P = .386), although self‑reported improvement was higher with 5 mg (92% vs 84%; P = .009). Adverse events, notably pedal edema and dizziness, were more common in the 5‑mg group (P = .024), while heart rate and both systolic and diastolic blood pressure remained similar between groups.

The study authors concluded that oral minoxidil at 2.5 mg/day provided comparable efficacy to the 5 mg/day dose in treating male AGA, while offering a better safety profile. They further noted that these results support 2.5 mg/day as an appropriate starting dose in clinical settings.

High-Dose

A 2025 retrospective multicenter study in Brazil and Spain evaluated high-dose oral minoxidil (>5 mg/day) for AGA in 57 men. Most received 10 mg nightly, often alongside finasteride or dutasteride, after at least one year on low-dose minoxidil (≤5 mg/day).[30]Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Saceda-Corralo, D., Jiminez-Cauhe, J., Ortega-Quijano, D., Pirmez, R., Galvan, S. (2025). High-dose Oral Minoxidil for the Treatment of Androgenetic … Continue reading

After 9-12 months, 45.6% improved hair density by 10-30%, 17.5% improved by >50%, and 17.5% improved by <10%, while 7% saw no change.

Adverse effects occurred in 24.6%, mainly hypertrichosis (17.5%) and tachycardia (3.5%), with hypertensive patients tolerating treatment well under blood-pressure monitoring.

The authors concluded that high-dose oral minoxidil may benefit selected men with AGA refractory to standard therapy, but variability in response and increased side effects highlight the need for gradual dose escalation and further research in larger, more diverse populations.

Based on this evidence, we think that starting off with a low dose can be effective (and potentially safer) than the standard oral minoxidil dose. However, if you are struggling to see benefits, there is efficacy data for high doses. It would be interesting for a study to compare how much more effective ultra-high doses of minoxidil are for hair regrowth than 5 mg (for example). This would help us to determine whether it is worth the potential increased side effects.

Furthermore, those who decide to go the low-dose oral minoxidil route may find it beneficial to add spironolactone to their routine.

Is Oral Minoxidil Safe?

Oral minoxidil has gained attention as an effective treatment for hair loss, but questions about its safety persist, particularly in comparison to the topical form. Here’s what the evidence shows.

Cardiovascular Risks: Myocardial and Pericardial Effusion

There are documented cases where people taking oral minoxidil developed pericardial effusion (fluid around the heart) and even pericarditis, sometimes at low doses used for hair loss.[31]Dlova, N.C., Jacobs, T., Singh, S. (2022). Pericardial, pleural effusion and anasarca: A rare complication of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss. JAAD Case Reports. 11(28). 94-96. Available at: … Continue reading These events are rare but have prompted caution within the medical community.

Severe cardiovascular complications like pericardial effusion have been recorded the high doses (10-40 mg) used for hypertension, with rates around 3% in these populations.[32]Bentivegna, K., Zhou, A.E., Adalsteinsson, J.A., Sloan, B. (2022). Letter in reply: Pericarditis and peripheral edema in a healthy man on low-dose oral minoxidil therapy. JAAD Case Reports. 20(29). … Continue reading However, it should be noted that this was reported in the 1980s in patients with severe hypertension, with no recent data available.

However, at the lower doses used for hair loss (0.25-5 mg), these complications are much less common and appear to be idiosyncratic (based on the individual response) rather than dose-dependent.[33]Gupta, A.K., Bamimore, M.A., Abdel-Qadir, H., Williams, G., Tosti, A., Piguet, V., Talukder, M. (2024). Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil and Associated Adverse Events: Analyses of the FDA Adverse Event … Continue reading

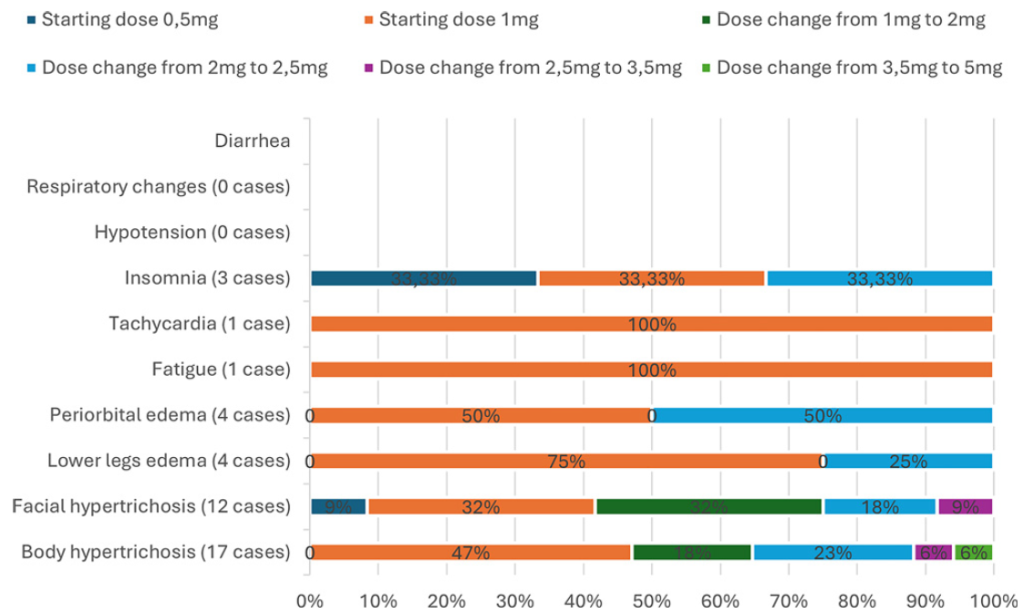

Large observational studies and clinical experience with thousands of patients using low-dose oral minoxidil have not shown a significant increase in life-threatening cardiac events.[34]Vano-Galvan, S., Pirmez, R., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Saceda-Corralo, D., Rodrigues-Barata, R., Jiminez-Cauhe, J., Koh, W.L., Poa, J.E., Jerjen, R., de Carvalho, L.T., John, J.M., … Continue reading Most side effects are mild and reversible with dose adjustments or discontinuation of the medication.[35]Bloch, D.L., Carlos, R.M.D. (2025). Side Effects’ Frequency Assessment of Low Dose Oral Minoxidil in Male Androgenetic Alopecia Patients. Skin Appendage Disorders. 11(1). 14-18. Available at: … Continue reading

Autopsy reports from patients who took extremely high doses (e.g., 60 mg) have not consistently shown pericardial or myocardial effusion, suggesting the risk is not universal or inevitable, even at high exposures.[36]Sobota, J.T. (1989). Review of cardiovascular findings in humans treated with minoxidil. Toxicologic pathology. 17(1 Pt 2). 193-202. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/019262338901700115

Subclinical and EKG Changes

At high doses, minoxidil can cause changes in the heart’s electrical activity, and this has been observed in up to 60-90% of patients.[37]Hall, D., Charocopos, F., Froer, K.L., Rudolph, W. (1979). ECG changes during long-term minoxidil therapy for severe hypertension. Archives of Internal Medicine. 139(70. 790-794. Available at: PMID: … Continue reading These changes are typically subclinical, meaning they do not cause symptoms or progress to life-threatening arrhythmias, and often resolve with continued use or a reduction in the dose.

In studies of low-dose minoxidil for hair loss, only minor, asymptomatic EKG changes have been observed, with no evidence of clinically significant heart rhythm disturbances in otherwise healthy individuals.[38]Jiminiez-Cauhe, J., Pirmez, R., Muller-Ramos, P., Melo, D.F., Ortega-Quijano, D., Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Saceda-Corralo, D., Gil-Redondo, R., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Dias-Sanabria, B., Restom, D., … Continue reading

Real-World Safety: Observational and Clinical Data

The most common side effects at hair loss doses are hypertrichosis, mild ankle swelling, lightheadedness, and occasional palpitations.[39]Bloch, D.L., Carlos, R.M.D. (2025). Side Effects’ Frequency Assessment of Low Dose Oral Minoxidil in Male Androgenetic Alopecia Patients. Skin Appendage Disorders. 11(1). 14-18. Available at: … Continue reading Serious cardiac events are exceedingly rare. Most patients who experience side effects can continue treatment with dose adjustments. Only a small fraction discontinue due to adverse effects.

This favorable safety profile is not only a function of the lower dose but may also reflect the generally healthier status of this population compared to those prescribed high-dose minoxidil for hypertension. Most studies examining minoxidil for hair growth routinely exclude individuals with significant underlying disease.

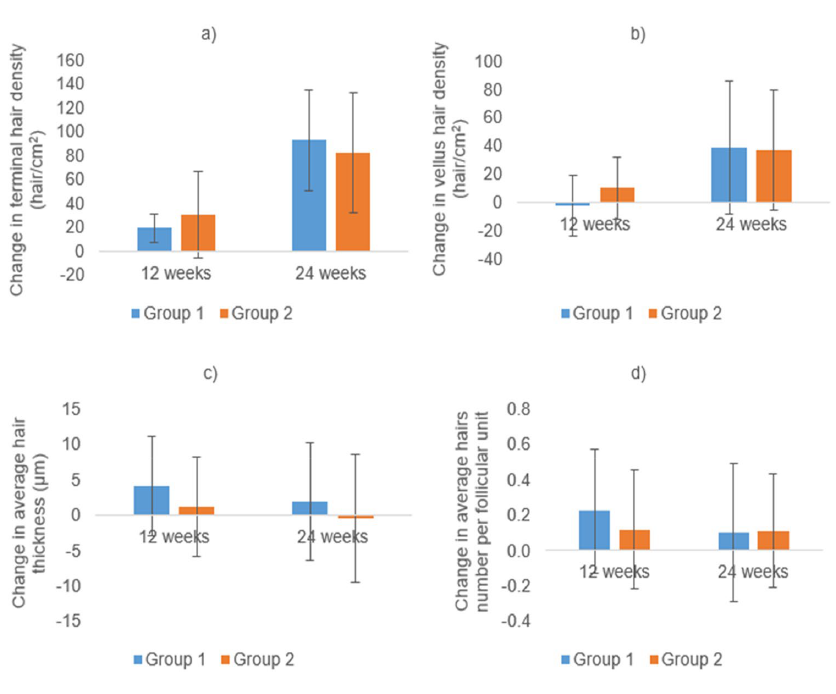

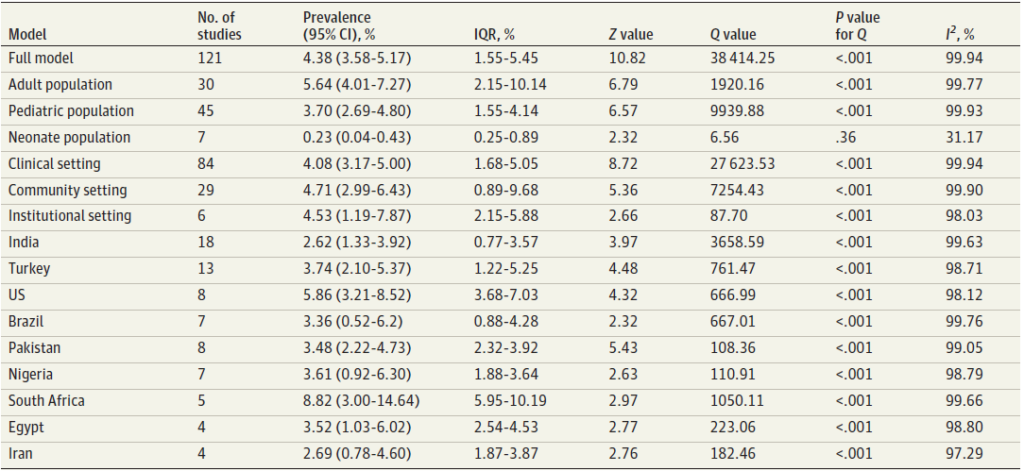

Figure 3: Frequency of side effects using low-dose oral minoxidil according to dose.[40]Bloch, D.L., Carlos, R.M.D. (2025). Side Effects’ Frequency Assessment of Low Dose Oral Minoxidil in Male Androgenetic Alopecia Patients. Skin Appendage Disorders. 11(1). 14-18. Available at: … Continue reading

Experts recommend that patients, especially those with pre-existing heart, kidney, or liver conditions, be monitored by a healthcare provider when starting oral minoxidil.[41]Gupta, A.K., Bamimore, M.A., Haber, R., Williams, G., Piguet, V., Talukder, M. (2024). The Role of Patient- and Drug-Related Factors in Oral Minoxidil and Pericardial Effusion: Analyses of Data from … Continue reading

How Can I Make Oral Minoxidil Safer?

Here are a number of strategies you can use to help minimize side effects while maintaining results:

- Titrate Your Dose

Begin with the lowest effective dose and increase gradually if needed. This approach helps your body adjust and can reduce the risk of side effects, such as swelling, dizziness, or heart palpitations.

Based on the published evidence, we believe that the best balance between efficacy and safety is 2.5 mg daily for men and 0.25-1.25 mg daily for women.

- Split the Dose: Morning & Evening

Oral minoxidil has a short half-life (about 3 hours). Taking your daily dose all at once can cause higher peak blood levels, increasing the risk of side effects. Taking half in the morning and half in the evening can help keep blood levels steadier and may reduce side effects.

- Consider Sublingual Administration

Taking minoxidil sublingually (letting it dissolve under your tongue) allows the drug to enter your bloodstream directly, bypassing the liver’s first-pass metabolism. Sublingual minoxidil becomes active when it reaches tissues with the right enzymes, such as those in the scalp, potentially enhancing its effectiveness. Studies suggest that sublingual minoxidil can lead to lower peak blood concentrations and fewer systemic side effects, while still promoting hair growth.[42]Guo, R-X., Zhao, Y-K., Hu, K-J., Hia, K.M., Shi, W., Yi, Y-X., Gong, H-Y., Wang, J-B., Gao, Y. (2025). Research progress in the treatment of non-scarring alopecia: mechanism and treatment. Frontiers … Continue reading

- Switch To Topical Minoxidil

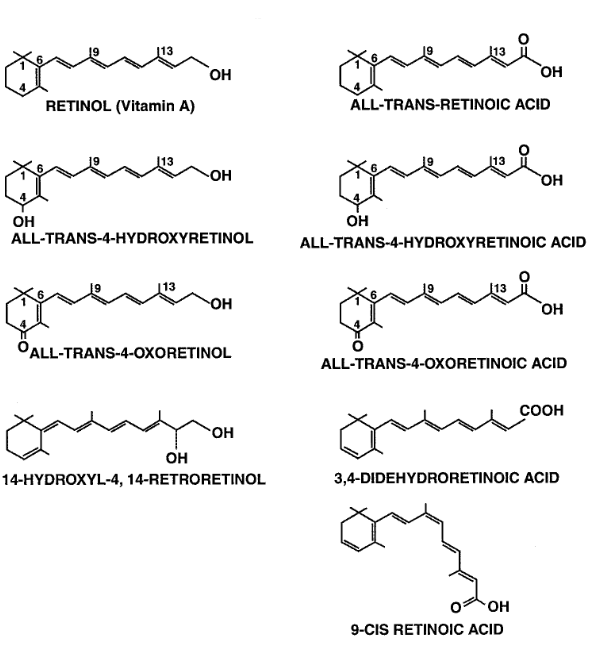

If oral minoxidil isn’t working for you because of the side effects, consider switching to the topical formulation. And, if you’re able to tolerate a 2% or 5% formulation well, you could consider adding microneedling or retinoic acid to boost your gains.

To find out more information about the potential side effects and how to avoid them, watch our video: Oral Minoxidil: How to Eliminate Side Effects.

Is Oral Minoxidil Better Than Topical Minoxidil?

Deciding between oral and topical minoxidil involves weighing efficacy, convenience, safety, and individual response.

Efficacy: Which Works Better?

At standard strengths, both 5% topical minoxidil and low-dose oral minoxidil (1-5 mg) show similar efficacy in clinical trials for total area hair count (TAHC).[43]Fazal, F., Malik, B.H., Malik, H.M., Sabir, B., Mustafa, H., Ahmed, M., Abid, A., Adil, M.L., Shafi, U., Saad, M. (2025). Can oral minoxidil be the game changer in androgenetic alopecia? A … Continue reading However, oral minoxidil often leads to slightly thicker, more robust regrowth for some users, especially those with diffuse thinning.

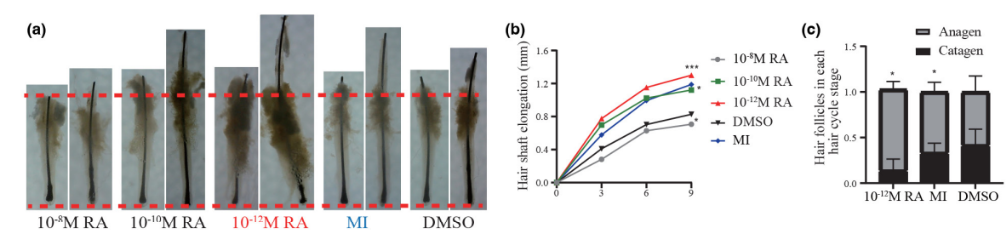

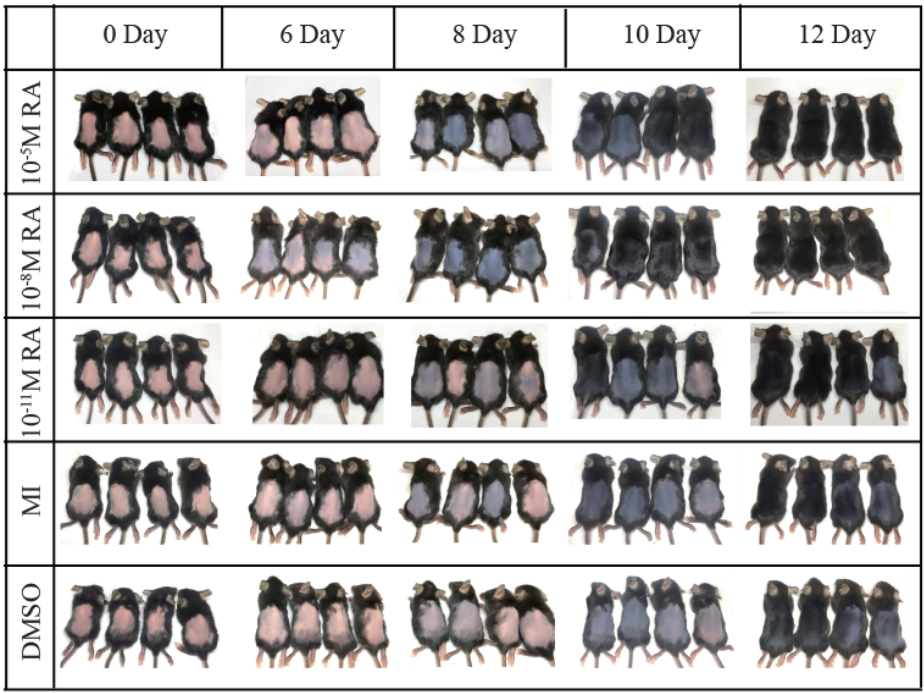

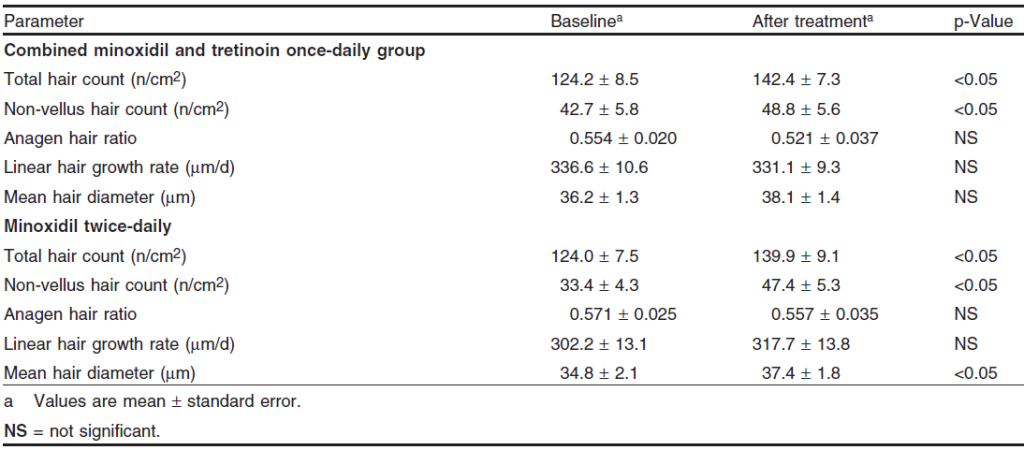

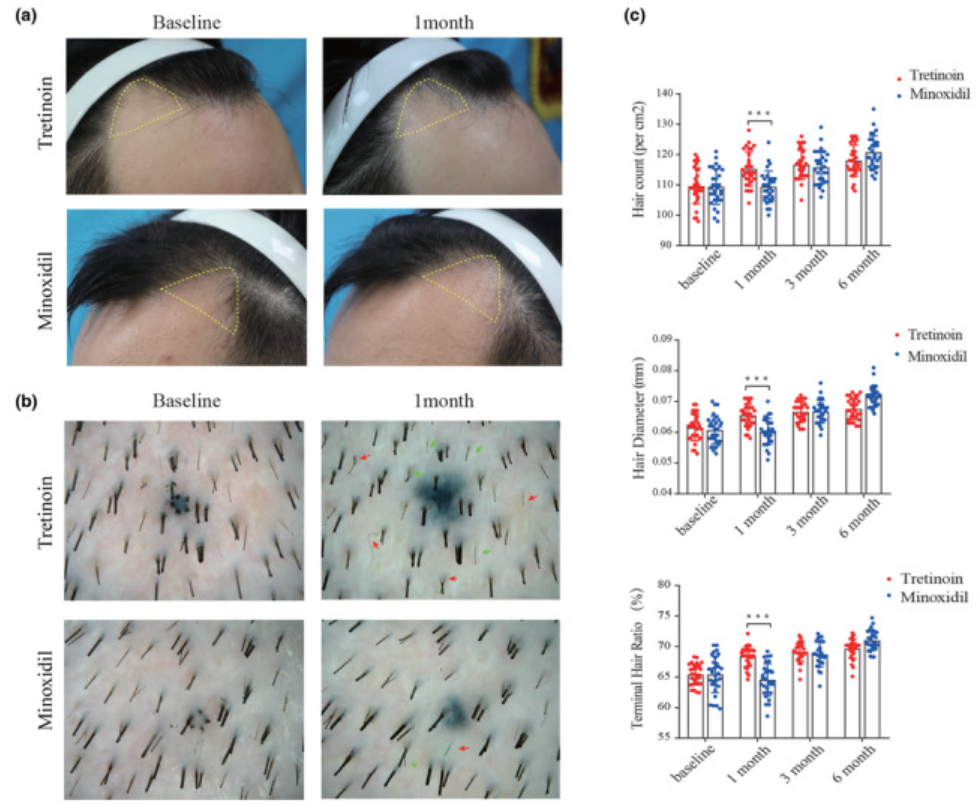

When topical minoxidil is combined with enhancers, such as retinoic acid, at concentrations of 7-8% (or higher), the results can surpass those seen with oral minoxidil. Our members consistently report better outcomes with these combinations, even compared to 5 mg oral minoxidil.

Advantages of Oral Minoxidil

- More convenient: Oral minoxidil is taken as a pill once or twice daily, while topical minoxidil requires 1-2 daily applications, which can be inconvenient and affect adherence.

- No product residue: Oral minoxidil eliminates the sticky residue and styling issues associated with topical solutions.

- Cost-effective: Oral minoxidil is generally about half the price of topical formulations.

- Bypasses scalp enzyme variance: Oral minoxidil is activated in the liver, sidestepping the variability in scalp sulfotransferase enzyme activity that limits topical efficacy for some users.[44]Goren, A., Shapiro, J., Roberts, J., McCoy, J., Desai, N., Zarrab, X., Pietrzak, A., Lotti, T. (2014). Clinical utility and validity of minoxidil response testing in androgenetic alopecia. … Continue reading

- Less scalp irritation: Oral minoxidil avoids the dryness, irritation, and brittleness sometimes caused by topical applications.

- May improve beard density: Some users report increased facial hair growth, which can be a benefit or drawback, depending on personal preference.[45]Pirmez, R., Salas-Callo, C-I. (2020). Very-low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia: a study with quantitative trichoscopic documentation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. … Continue reading

- Better for brittle hair: Those with fragile or chemically treated hair may prefer oral minoxidil to avoid further brittleness.

Drawbacks of Oral Minoxidil

- Unwanted body hair: Oral minoxidil can cause hair growth on other parts of the body, which is especially concerning for women.

- Systemic side effects: Risks include fluid retention, rare cardiovascular effects, headaches, and skin rashes. These are uncommon at hair loss doses (0.25-5 mg), but still possible.

- Prescription required: Unlike topical minoxidil, oral formulations require a prescription from a doctor.

Advantages of Topical Minoxidil

- Fewer systemic effects: Topical minoxidil acts locally, so there’s less risk of systemic side effects.

- Easier access: Available over-the-counter without a prescription.

- Customizable formulations: Various strengths and enhancers (like retinoic acid) can be tailored to individual needs.

Drawbacks of Topical Minoxidil

- Variable response: Efficacy depends on scalp enzyme activity, which varies between individuals.

- Scalp irritation: Some may experience irritation, dryness, or increased hair brittleness.[46]Shadi, Z. (2023). Compliance to Topical Minoxidil and Reasons for Discontinuation among Patients with Androgenetic Alopecia. Dermatological Therapy (Heidelb). 13(5). 1157-1169. Available at: … Continue reading

- Residue and Compliance: Daily application can be messy and inconvenient, which can impact adherence.

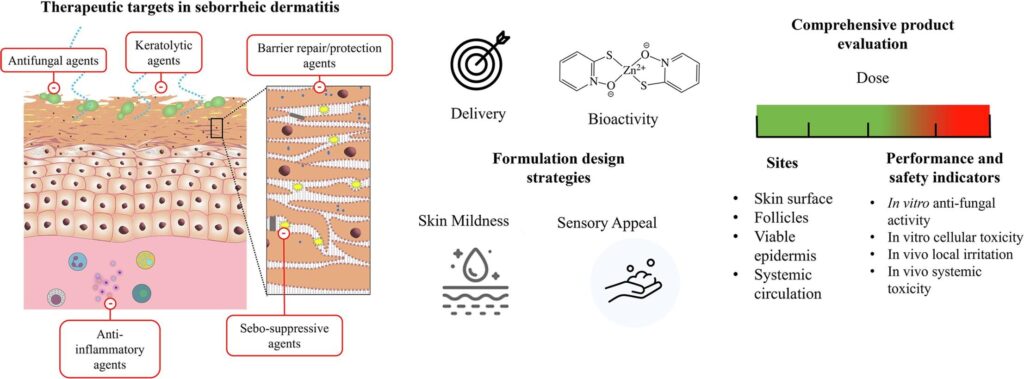

Special Considerations: Scalp Inflammation

Underlying scalp inflammation (like seborrheic dermatitis) can reduce the effectiveness of topical minoxidil.[47]Mahe, Y.F., Cheniti, A., Tacheau, C., Antonelli, R., Planard-Luong, L., de Bernard, S., Buffat, L., Barbarat, P., Kanoun-Copy, L. (2021). Low-Level Light Therapy Downregulates Scalp Inflammatory … Continue reading Addressing inflammation is crucial before starting or modifying any hair loss treatment.

The bottom line:

Oral minoxidil is more convenient, cost-effective, and bypasses scalp enzyme limitations, making it a strong option, especially for those who don’t respond to topical or want to avoid scalp irritation.

High-strength topical minoxidil, when combined with treatments such as retinoic acid and microneedling, often delivers the best results but comes with more hassle, a higher cost, and a greater risk of scalp irritation.

Standard topical minoxidil remains a solid, accessible first-line option, especially for those who prefer to avoid systemic medications.

Ultimately, the best choice depends on your hair loss pattern, your response to treatment, your tolerance for side effects, and your lifestyle.

Can You Take Them Together?

Yes, it is possible to use oral and topical minoxidil together; however, this approach should only be considered under the supervision of a healthcare provider. Combining both forms may provide a more robust treatment for hair loss.

Some dermatologists suggest that using both can enhance efficacy, especially for individuals who have not achieved optimal results with one form alone. However, using both simultaneously increases the risk of side effects. Therefore, the decision to combine oral and topical minoxidil should be made with professional guidance to ensure proper dosing and monitoring for adverse effects.

Who are the Best Candidates for Oral Minoxidil?

According to the research we just outlined, you’re a good candidate for oral minoxidil if:

- You’re a male with AGA, TE, or permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia who doesn’t respond to topical minoxidil and/or finds it difficult to comply with the treatment protocol.

- You’re a female with FPHL, TE, or permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia who doesn’t respond to topical minoxidil and/or finds it difficult to comply with the treatment protocol, and you’re okay with a chance of increased hair growth in other places of the body.

- You have a healthy liver and normal to high blood pressure. If you are somewhat hypertensive, oral minoxidil may have the joint benefit of hair growth and antihypertensive effects.

- You’re a female who’s already taking spironolactone for FPHL and wants to see better results, or has seen a plateau with spironolactone alone.

- You’re an AA patient resistant to traditional immunomodulatory treatment.

- You suffer from a brittle hair disorder or hair loss and brittle hair and want to avoid exacerbating brittleness with topical minoxidil.

- You can obtain a prescription.

On the other hand, you’re not a good candidate for oral minoxidil if…

- You’re a female who’s not comfortable with the idea of increased hair growth outside of the scalp.

- You regularly drink alcohol, which can exacerbate the antihypertensive effects of minoxidil.

- You have or have had kidney, cardiovascular, or liver issues.

- You’re pregnant or planning on becoming pregnant.

- You’re currently taking another vasodilating/antihypertensive drug or a muscle relaxer like tizanidine. Taking two vasodilating drugs at once can increase the risk of side effects associated with low blood pressure.

What Are The Best Practices for Taking Oral Minoxidil?

When taking oral minoxidil for hair loss, it’s best to start with the lowest effective dose, typically 2.5 mg daily for men and 0.25–1.25 mg daily for women. The dose should be increased gradually only if needed, under the supervision of a healthcare provider. Splitting the total daily dose into morning and evening halves can help maintain steady blood levels and reduce the risk of side effects, such as palpitations, swelling, or dizziness.

Sublingual administration (allowing the tablet to dissolve under your tongue) is an alternative that may further minimize systemic side effects by bypassing the liver’s first-pass metabolism, potentially making the medication more tolerable for individuals who are sensitive to it. Throughout treatment, monitor for common side effects, such as unwanted hair growth (hypertrichosis), ankle swelling, or lightheadedness, and promptly report any serious symptoms, including chest pain or significant changes in heart rate.

Regular check-ins with your healthcare provider are essential, especially if you have underlying heart, kidney, or liver issues or take other medications that affect blood pressure. If side effects occur, consider reducing the dose, splitting it further, switching to a sublingual or topical minoxidil formulation, or discontinuing use as advised by your healthcare provider.

Avoid combining oral minoxidil with other vasodilators or muscle relaxants without consulting a healthcare professional. Address any scalp inflammation before starting or adjusting therapy to maximize results and safety.

Final Thoughts

Oral minoxidil has emerged as a compelling option for individuals seeking effective hair loss treatment, offering robust regrowth potential and convenience for both men and women who may not respond to or tolerate topical formulations. While research supports its efficacy across a range of hair loss conditions, including androgenic alopecia and chronic telogen effluvium, it is not without risks, most notably rare but serious cardiovascular side effects, as well as more common issues such as unwanted hair growth and mild edema. For many, oral minoxidil represents a powerful, evidence-based tool in the fight against hair loss, but its use should always be informed, individualized, and guided by medical expertise to ensure both safety and satisfaction. If you are a good candidate and proceed thoughtfully, oral minoxidil can play a pivotal role in your hair restoration journey.

References[+]

References ↑1 Patel, P., Nessel, T.A., Kumar, D. (2023). Minoxidil. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/book/NBK482378/ Accessed: July 2025 ↑2 Nestor, M.S., Ablon, G., Gade, A., Han, H., Fischer, D.L. (2021). Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia: Efficacy, side effects, compliance, financial considerations, and ethics. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 20(12). 3759-3781. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14537 ↑3 Pietrauszka, K., Bergler-Czop, B. (2020). Sulfotransferase SULT1A1 activity in hair follicle, a prognostic marker of response to the minoxidil treatment in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a review. Advances in Dermatology and Allergology. 39(3). 472-478. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5114/ada.2020.99947 ↑4 Chitalia, J., Dhurat, R., Goren, A., McCoy, J., Kovacevic, M., Situm, M., Naccarato, T., Lotti, T. (2018). Characterization of follicular minoxidil sulfotransferase activity in a cohort of pattern hair loss patients from the Indian Subcontinent. Dermatologic Therapy. 31(6). E12688. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12688 ↑5, ↑25 Suchonwanit, P., Thammarucha, S., Leerunyakul, K. (2019). Minoxidil and its use in hair disorders: a review. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 13. 2777-2786. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S214907 ↑6 Beach, R.A. (2018). Case series of oral minoxidil for androgenetic and traction alopecia: Tolerability & the five C’s of oral therapy. Dermatologic Therapy. 31(6). E12707. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12707 ↑7 Gupta, A.K., Talukder, M., Shemar, A., Priaccini, B.A., Tosti, A. (2023). Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil for Alopecia: A Comprehensive Review. Skin Appendage Disorders. 9(6). 423-437. Available at: https://doi.org/10.115//000531890 ↑8 Suchonwanit, P., Thammarucha, S., Leerunyakul, K. (2019). Minoxidil and its use in hair loss disorders. Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 13. 2777-2786. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S214907 ↑9 Kwack, M.H., Kang, B.M., Kim, M.K., Kim, J.C., Sung, Y.K. (2011). Minoxidil activates ꞵ-catenin pathway in human dermal papilla cells: a possible explanation for its anagen prolongation effect. Journal of Dermatological Science. 62(3). 154-159. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dermsci.2011.01.013 ↑10 Wang, X., Liu, Y., He, J., Wang, J., Chen, X., Yang, R. (2022). Regulation of signaling pathways in hair follicle stem cells. Burns Trauma. 10. 1-19. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/burnst/tkac022 ↑11 Kang, J-I., Choi, K.Y., Han, S-C., Nam, H., Lee, G., Kang, J-H., Koh, Y.S., Hyun, J.W., Yoo, E.S., Kang, H.K. (2022). 5-Bromo-3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde Promotes Hair Growth through Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin and Autophagy Pathways and Inhibition of TGF-β Pathways in Dermal Papilla Cells. Molecules. 27(7). 2176. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27072176 ↑12 Jan, J.H., Kwon, O.S., Chung, J.H., Cho, K.H., Eun, H.C., Kim, K.H. (2004). Effect of minoxidil on proliferation and apoptosis in dermal papilla cells of human hair follicle. Journal of Dermatological Science. 34(2). 91-98. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dermsci.2004.01.002 ↑13 Nagai, N., Iwai, Y., Sakamoto, A., Otake, H., Oaku, Y., Abe, A., Nagahama, T. (2019). Drug Delivery System Based on Minoxidil Nanoparticles Promotes Hair Growth in C57BL/6 Mice. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 1(14). 7921-7931. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S225496 ↑14 Shin, D.W. (2022). The physiological and pharmacological roles of prostaglandins in hair growth. The Korean Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 26(6). 405-415. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4196/kjpp.2022.26.6.405 ↑15 Majewski, M., Gardas, K., Waskiel-Burnat, A., Ordak, M., Rudnicka, L. (2024). The Role of Minoxidil in Treatment of Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 13(24). 7712. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13247712 ↑16 Fechine, C.O.C., Valente, N.Y.S., Romiti, R. (2022). Lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia: review and update of diagnostic and therapeutic features. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 97(3). 348-357. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abd.2021.08.008 ↑17 Ramos, M.P., Sinclair, R.D., Kasprzak, M., Miot, H.A. (2020). Minoxidil 1 mg oral versus minoxidil 5% topical solution for the treatment of female-pattern hair loss. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 82(1). 252-253. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.060 ↑18 Sinclair, R.D. (2018). Female pattern hair loss: a pilot study investigating combination therapy with low-dose oral minoxidil and spironolactone. International Journal of Dermatology. 57(1). 104-109. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.13838 ↑19 Lueangarun, S., Panchaprateep, R., Tempark, T., Noppakun, N. (2015). Efficacy and safety of oral minoxidil 5 mg daily during 24-week treatment in male androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 72(5). AB113. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.466 ↑20, ↑21 Jiminiez-Couche, J., Saceda-Corralo, D., Rodrigues-Barata, R., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Fernandez-Nieto, D., Vano-Galvan, S. (2019). Effectiveness and safety of low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia. 81(2). 648-649. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.054 ↑22, ↑23 Pirmez, R., Salas-Callo, C-I. (2020). Very-low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia: A study with quantitative trichoscopic documentation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 82(1). E21-e22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.084 ↑24 Perera, E., Sinclair, R. (2017). Treatment of chronic telogen effluvium with oral minoxidil: A retrospective study. F1000 Research. 6. 1650. Available at: https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11775.1 ↑26 Wambier, C.G., Craiglow, B.G., King, B.A. (2021). Combination tofacitinib and oral minoxidil treatment for severe alopecia areata. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 85(3). 743-745. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.080 ↑27 Yang, X., Thai, K-E. (2016). Treatment of permanent chemotherapy-induced alopecia with low-dose oral minoxidil. The Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 57(4). E120-e132. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajd.12350 ↑28 Varma, D. (2025). Oral Minoxidil 2.5 mg vs 5 mg: Similar Efficacy for Androgenetic Alopecia in Men. Medscape. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/oral-minoxidil-2-5-mg-vs-5-mg-similar-efficacy-androgenetic-2025a1000ox7?reg=1 Accessed: October 2025 ↑29 Fonseca, L.P.C., Miot, H.A., Chaves, C.R.P., Ramos, P.M. (2025). Oral minoxidil 2.5 mg versus 5 mg for male androgenetic alopecia: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. S0190-9622(25)02819-1 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2025.09.031 ↑30 Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Saceda-Corralo, D., Jiminez-Cauhe, J., Ortega-Quijano, D., Pirmez, R., Galvan, S. (2025). High-dose Oral Minoxidil for the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. Actas Dermo-Sifiliograficas. 116. T769 – T772. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2025.05.018 ↑31 Dlova, N.C., Jacobs, T., Singh, S. (2022). Pericardial, pleural effusion and anasarca: A rare complication of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss. JAAD Case Reports. 11(28). 94-96. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.07.044 ↑32 Bentivegna, K., Zhou, A.E., Adalsteinsson, J.A., Sloan, B. (2022). Letter in reply: Pericarditis and peripheral edema in a healthy man on low-dose oral minoxidil therapy. JAAD Case Reports. 20(29). 110-111. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.08.057 ↑33 Gupta, A.K., Bamimore, M.A., Abdel-Qadir, H., Williams, G., Tosti, A., Piguet, V., Talukder, M. (2024). Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil and Associated Adverse Events: Analyses of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) With a Focus on Pericardial Effusions. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 24(1). E16574. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.16574 ↑34 Vano-Galvan, S., Pirmez, R., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Saceda-Corralo, D., Rodrigues-Barata, R., Jiminez-Cauhe, J., Koh, W.L., Poa, J.E., Jerjen, R., de Carvalho, L.T., John, J.M., Salas-Callo, C.I., Vincenzi, C., Yin, L., Lo-Sicco, K., Piraccini, B.M., Rudnicka, L., Shapiro, J., Tosti, A., Sinclair, R., Bhoyrul, B. (2021). Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: A multicenter study of 1404 patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 84(6). 1644-1651. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054 ↑35, ↑39, ↑40 Bloch, D.L., Carlos, R.M.D. (2025). Side Effects’ Frequency Assessment of Low Dose Oral Minoxidil in Male Androgenetic Alopecia Patients. Skin Appendage Disorders. 11(1). 14-18. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1159/000539969 ↑36 Sobota, J.T. (1989). Review of cardiovascular findings in humans treated with minoxidil. Toxicologic pathology. 17(1 Pt 2). 193-202. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/019262338901700115 ↑37 Hall, D., Charocopos, F., Froer, K.L., Rudolph, W. (1979). ECG changes during long-term minoxidil therapy for severe hypertension. Archives of Internal Medicine. 139(70. 790-794. Available at: PMID: 36861 ↑38 Jiminiez-Cauhe, J., Pirmez, R., Muller-Ramos, P., Melo, D.F., Ortega-Quijano, D., Moreno-Arrones, O.M., Saceda-Corralo, D., Gil-Redondo, R., Hermosa-Gelbard, A., Dias-Sanabria, B., Restom, D., Porrino-Bustamante, M.L., Pindado-Ortega, C., Berna-Rico, E., Fernandez-Nieto, D., Ramos, M., Jaen-Olasolo, P., Vano-Galvan, S. (2024). Safety of Low-Dosr Oral Minoxidil in Patients With Hypertension and Arrhythmia: A Multicenter Study of 264 Patients. Actas Dermo-Sifiliograficas. 115(1). 28-35. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2023.07.019 ↑41 Gupta, A.K., Bamimore, M.A., Haber, R., Williams, G., Piguet, V., Talukder, M. (2024). The Role of Patient- and Drug-Related Factors in Oral Minoxidil and Pericardial Effusion: Analyses of Data from the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 24(2). E16732. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.16732 ↑42 Guo, R-X., Zhao, Y-K., Hu, K-J., Hia, K.M., Shi, W., Yi, Y-X., Gong, H-Y., Wang, J-B., Gao, Y. (2025). Research progress in the treatment of non-scarring alopecia: mechanism and treatment. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 26(1544068). Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2025.1544068 ↑43 Fazal, F., Malik, B.H., Malik, H.M., Sabir, B., Mustafa, H., Ahmed, M., Abid, A., Adil, M.L., Shafi, U., Saad, M. (2025). Can oral minoxidil be the game changer in androgenetic alopecia? A comprehensive review and meta-analysis comparing topical and oral minoxidil for treating androgenetic alopecia. Skin Health and Disease. 5(2). 95-101. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/skinhd/vzaf009 ↑44 Goren, A., Shapiro, J., Roberts, J., McCoy, J., Desai, N., Zarrab, X., Pietrzak, A., Lotti, T. (2014). Clinical utility and validity of minoxidil response testing in androgenetic alopecia. Dermatologic Therapy. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.12164 ↑45 Pirmez, R., Salas-Callo, C-I. (2020). Very-low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia: a study with quantitative trichoscopic documentation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 82(1). E21-e22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.084 ↑46 Shadi, Z. (2023). Compliance to Topical Minoxidil and Reasons for Discontinuation among Patients with Androgenetic Alopecia. Dermatological Therapy (Heidelb). 13(5). 1157-1169. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-023-00919-x ↑47 Mahe, Y.F., Cheniti, A., Tacheau, C., Antonelli, R., Planard-Luong, L., de Bernard, S., Buffat, L., Barbarat, P., Kanoun-Copy, L. (2021). Low-Level Light Therapy Downregulates Scalp Inflammatory Biomarkers in Men with Androgenetic Alopecia and Boost Minoxidil 2% to Bring a Sustainable Hair Regrowth Activity. Lasers in Surgery & Medicine. 53(9). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.23398 We’re thrilled to announce the arrival of Ulo: a haircare brand that offers best-in-class hair growth products and focuses on solving the biggest problems plaguing the hair loss industry.

Ulo’s core commitment to hair loss sufferers is its prioritization of evidence, personalization, and consumer safety. And there’s a reason we’re so confident in Ulo’s ability to deliver: we co founded the brand.

In fact, the Perfect Hair Health team was involved in every aspect of Ulo’s product development: its selection of manufacturers, ingredients, formulations, concentrations, & more. Now the product formulations for which we’ve been advocating for 10+ years are finally offered, all through a single provider.

Whether it’s over-the-counter serums or prescription products, Ulo represents the next evolution in telehealth haircare: one that puts the consumer first, sets realistic expectations, and supports customers at every step on their journey to better hair.

Below, we’ll detail our journey to launching Ulo, the problems Ulo solves, its core offerings, and why we currently consider Ulo to be a revolutionary step forward for consumers.

For those interested in this level of product personalization and support, Ulo is also offering 15% off all their products, forever. Any purchase made through the links in this article will result in a 15% discount applied to all product purchases, including all renewals. This is our thank you to you, and your opportunity to lock in a permanently discounted price on all products.

Why Ulo?

For 11 years, Perfect Hair Health has acted solely as a consumer advocacy resource for men and women fighting hair loss.

During this time, we never once endorsed a single hair growth product: no pill, supplement, topical, shampoo, or device. Instead, we focused entirely on educating hair loss sufferers on how to properly read studies, select treatments, and maximize their chances for hair regrowth.

For just a few examples of this commitment, see the following content pieces:

- What Causes Hair Loss? (Interactive Guide)

- Understanding Hair Loss Disorders (Interactive Guide)

- The Hair Loss Industry Is Broken: Evidence Quality Masterclass (Video)

- Nutrafol: The Problem With Their Clinical Studies (Company Investigation)

- Our Peer-Reviewed Studies (Publications)

- Independent Third-Party Lab Testing Results (Product Investigations)

But, as the hair loss industry continued to evolve, so too did its bad practices – particularly the sale of dangerous, improperly formulated products with ingredients that were “trending” on social media, but that lacked adequate efficacy and safety data.

For years, our organization called attention to these concerns – creating free evidence-based articles, videos, & interactive guides detailing these exact problems & how to protect yourself. And yet this entire time, as the hair loss industry expanded, we watched these problems only grow worse. We’ll detail several of them later in this article.

Two years ago, Perfect Hair Health was offered a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to become more than just a voice of advocacy. We were approached with an offer to go beyond education and to start solving the very problems that have plagued this industry for years.

This meant an opportunity to create products that could finally serve as the antidote to every bad practice currently employed by other haircare brands at scale.

Initially, we were skeptical. We’ve seen firsthand how other brands deprioritize consumer safety in the name of “business decisions,” like with brands that include corticosteroids in their Rx topicals to offset irritation and increase recurring purchases… but at the expense of the risk of long-term, permanent skin thinning for their patients.

If we were going to become involved in a brand, we would need full control over the entire production process for hair loss. We wanted the sole ability to fire compounding pharmacies that failed to meet purity standards. We wanted final say in every aspect of product development: the ingredients, concentrations, formulations, & more. Without this level of control, we would never be able to prioritize what’s right for the consumer over what’s right for business.

We were pleasantly surprised to find 100% alignment with those offering a partnership. With just how easy it is to “cut corners” in the hair loss industry, we can’t describe how refreshing it was to connect with others who actually wanted to do right by the consumer.

After much reflection, we decided to step off the sidelines as critics and instead, start building a brand that walked the walk and started solving the hair loss industry’s biggest problems.

That brand is Ulo: a telehealth company dedicated exclusively to hair growth, and founded on three key pillars: evidence, personalization, and consumer safety.

What Problems Need Solving In The Hair Loss Industry?

Over the years, we’ve watched haircare brands adopt a set of bad practices that seemed uniquely targeted toward their bottom line, rather than consumer interests.

We’ll detail just a few of these below, along with how Ulo solves these problems and sets the bar higher.

Problem #1: Mega-Dosed Topicals

Other telehealth brands are selling mega-dose versions of topical finasteride & topical dutasteride – letting people think it’s staying on the scalp, when in reality, the dose is 60x too high, so it leaks into the blood & causes hormonal changes to the same extent as oral finasteride.

Videos here and here. FDA warning here.

Ulo’s Solution: Low-Dose Topical Finasteride & Low-Dose Topical Dutasteride

Ulo offers two kinds of topical finasteride & topical dutasteride: low-dose and full-strength.

For those truly interested in localization, the lower-dose topicals are far more appropriate than the mega-dosed topicals sold by other telehealth brands. And even more encouragingly, Ulo offers full customization of either topical – with the ability to add in ingredients like 7% minoxidil, 0.01% retinoic acid (tretinoin), 0.2% caffeine, 0.01% melatonin, and 1% cetirizine – so prospective users can ensure better control over every ingredient, pending a prescription:

Ulo’s Topical Finasteride

- Low-Dose Topical Finasteride (Optional: Add Enhancers)

- Full-Strength Topical Finasteride (Optional: Add Enhancers)

Ulo’s Topical Dutasteride

- Low-Dose Topical Dutasteride (Optional: Add Enhancers)

- Full-Strength Topical Dutasteride (Optional: Add Enhancers)

Problem #2: Corticosteroids In Rx Topicals (Permanent Skin Thinning)

Brands are adding dangerous ingredients to their Rx topicals –– like corticosteroids. They do this because their serums often contain propylene glycol, which helps with ingredient penetration but also causes skin irritation. Yet rather than fix their formulations, brands offset the irritation with corticosteroids (hydrocortisone, fluocinolone, etc.). This works in the short-term, and very likely, causes permanent, irreversible skin thinning after years of uninterrupted use.

Article here. Video here. Study here.

Ulo’s Solution: No Corticosteroids, No Propylene Glycol, & Less-Irritating Formulations

Ulo doesn’t use propylene glycol in any of its topicals. Instead, its partner pharmacies have spent significant time developing & iterating base formulations containing water, alcohol, and glycol-like compounds – formulations that apply easily, dry quickly, allow for ample ingredient penetration into the hair follicles, and above all, are less irritating.

The end-result: Ulo’s topicals don’t need to add corticosteroids to mask irritation – because they were formulated properly from the start.

Note: some of Ulo’s optional ingredients – like retinoic acid (tretinoin) – can enhance the activation and penetration of minoxidil, but may also cause mild irritation in a subset of individuals. For those who discover they cannot tolerate retinoic acid (tretinoin), Ulo’s physician partners can easily remove this ingredient for them. This is a much better, much more sustainable alternative than simply masking irritation with a corticosteroid, especially given the long-term risks of skin irritation.

Ulo’s topicals can be found here, with a guide to help you select your offering here.

Problem #3: Selling Dangerous, “Trending” Ingredients

Other telehealth brands are offering “trending” drugs with long-term safety risks, like latanoprost. Originally developed to treat glaucoma, latanoprost is now widely added to Rx topicals for hair growth. The basis? Two small clinical studies, the longest of which ran for 9 months. The problem? The doses sold by telehealth brands are, at times, thousands of times higher than what was used to treat glaucoma. They absolutely go systemic. And there’s a permanent side effect that occurs in up to 20% of glaucoma patients using latanoprost – one that typically isn’t noticeable until after 12 months of use: the blackening of your irises, an effect that often persists even after quitting the medication. No studies exist evaluating this risk for topical latanoprost, and also, no telehealth brand seems to care.

Ulo’s Solution: No “Trending” Ingredients That Risk Your Safety. Ever.

Unless an off-label ingredient offers notable hair gains through mechanisms distinct from other Ulo ingredients – and unless that ingredient has a respectable safety profile – Ulo will not include it as an offering to its product line.

That means no Carbon 60. No copper peptides. No latanoprost. No bimatoprost.

Ulo focuses on getting you results without compromising your safety. While the telehealth brand does offer off-label ingredients to certain users pending a prescription, such as dutasteride, spironolactone, melatonin, caffeine, and cetirizine, it only does so if safety & efficacy thresholds are met to justify their inclusion for added hair gains.

This is distinct from many other companies out there who simply attempt to capture your interest in ingredients “trending” on social media, but without enough data to determine whether these ingredients are safe, effective, and right for you.

You can see a sample of Ulo’s ingredient selections & concentrations here.

Problem #4: Compounding Dutasteride Without Emulsifiers

Other telehealth brands are compounding drugs that can’t be compounded, like dutasteride. To differentiate from the competition, telehealth brands often compound drugs like dutasteride & minoxidil into a single capsule, claiming bigger hair gains than finasteride and the convenience of a single daily pill.

The truth? When these companies “compound” dutasteride, they turn it from a soft gel into a powder, and inadvertently, they destroy its bioavailability, rendering dutasteride less effective than finasteride & causing major hair loss for customers who unknowingly switch to the 2-in-1 pills.

We have the lab tests to prove it. Post here. Video here.

Ulo’s Solution: No Compounded Dutasteride. Just The Real Thing.

Rather than offer compounded dutasteride, Ulo offers dutasteride as a soft gel – and in a formulation that has undergone bioequivalence testing, such that the efficacy should match that of the studies showing oral dutasteride outperformed oral finasteride for hair gains.

This is a distinction unrivaled by many other brands. Rather than sell you convenience in a 2-in-1 pill, Ulo sells you what works.

Better yet, Ulo still offers both oral dutasteride and oral minoxidil to those who want to multi-target their hair loss. They are just delivered as separate pills, in separate formulations, to maximize your potential for hair growth.

You can see Ulo’s oral Rx offerings here.

Beyond Ulo’s Products: Personal Support, Every Step Of The Way, Through Ulo’s Partner Physicians

As part of Ulo’s commitment to consumers, all subscriptions to their Rx product lines come with unlimited access to partner physicians – one of whom you’ll personally partner with to support your hair growth journey.

What does this look like? A completely different experience compared to other brands:

-

- Real customization: dosing & ingredient adjustments made by our partner physicians depending on your goals & real-time experiences with the products.

- Realistic expectations: separate “possibility” from “probability”. Our network physicians rely on clinical data to set realistic responses to your hair loss medications, including guides for when regrowth starts, when it might plateau, and what to do next to escalate your current protocol.

- Unrivaled personal support: the ability to contact a doctor, any time, through Ulo’s portal. Someone in your corner who not only assumes care for you, but also wants to help you achieve the best possible outcomes.

We hope you feel the difference. This piece is something we see other brands “promise”, but rarely deliver. It’s time to change that.

15% Off All Ulo Orders, Forever

Ulo is a part of the Perfect Hair Health ecosystem, and as a thank you for being a part of our community, all orders made through this article will automatically receive 15% off the purchase price, forever. That includes all future renewals, so long as the orders are made through these links.

We hope you enjoy everything Ulo has to offer. We certainly love the product line and are thrilled that we finally have the chance to offer products in the exact formulations for which we’ve advocated over the past 10+ years.

We wish you the best with your hair health journey, and we look forward to supporting you every step of the way.

OS-01 is a topical scalp serum developed by OneSkin, a biotech company based in San Francisco. Marketed as both an anti-aging skin treatment and a hair regrowth product, OS-01 aims to address hair thinning by targeting cellular senescence in the scalp. The serum has gained attention through social media and interviews with the company’s CEO, Carolina Reis Oliveira. In this article, we will examine what OS-01 is, explore the science of cellular senescence and its role in hair loss, and assess the evidence behind OS-01’s claims as a potential treatment for androgenetic alopecia.

Key Takeaways:

- Branding. OS-01 has positioned itself as a biotech-backed anti-aging and hair regrowth serum from OneSkin, a company known for its focus on longevity science. The branding strongly emphasizes scientific credibility and a “rooted in science” approach.

- Unique Selling Point. OS-01 is a peptide that specifically targets cellular senescence in the scalp, aiming to rejuvenate the hair follicle microenvironment by modulating the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

- Clinical Support. OneSkin reports a 6-month third-party clinical study showing improvements in hair density, thickness, and hair cycling when used with daily dermarolling. However, these results have not been published in peer-reviewed journals and rely on company-provided summaries.

- Concerns. Key concerns include the lack of independently published human data, reliance on dermarolling for efficacy, marketing claims that oversimplify complex skin and hair biology, and typical limitations seen in brand-led before-and-after photos.

- Evidence Quality. The OS-01 serum scored 31/100 for evidence quality by our metrics.

- Recommendations. We recommend that OS-01 consider publishing the results of their 6-month pilot study and, ideally, conduct a larger, registered, placebo-controlled clinical trial.

All-Natural Hair Topical

The top natural ingredients for hair growth, all in one serum.

Take the next step in your hair growth journey with a world-class natural serum. Ingredients, doses, & concentrations built by science.

*Only available in the U.S. Prescriptions not guaranteed. Restrictions apply. Off-label products are not endorsed by the FDA.

What Is OS-01?

OS-01 for hair is a topical scalp serum developed by OneSkin, a biotech company based in San Francisco, as both an anti-aging skin product and a hair regrowth product. The product is claimed to address hair thinning and loss by targeting the biological process of cellular senescence in the scalp.[1]OneSkin. (no date). Rooted in Science: The Clinical Evidence Supporting OS-01 Hair. Available at: … Continue reading

The product is sold in 1.7 fl oz bottles, available in 1-, 3-, or 6-month supplies, and comes with a dermaroller for $69, $207, or $424.

OS-01 for hair serum bottles.

The product contains a number of ingredients, of which you can see the whole list here:

“Water, Glycerin, 1,2-Hexanediol, Butylene Glycol, Hydroxyacetophenone, Panthenol, Inulin, Helianthus Annuus (Sunflower) Sprout Extract, Cellulose Gum, Alpha-Glucan Oligosaccharide, Tetrasodium Glutamate Diacetate, Propanediol, Morus Nigra Leaf Extract, Arginine, Acetyl Tyrosine, Rehmannia Chinensis Root Extract, Pentylene Glycol, Sodium PCA, Erythritol, Chondrus Crispus, PEG-12 Dimethicone, Oryza Sativa (Rice) Bran Water, Decapeptide-52*, Calcium Pantothenate, Zinc Gluconate, Sodium Benzoate, Niacinamide, Ornithine HCL, Caprylyl Glycol, Polyquaternium-11, Citrulline, Hydrolyzed Soy Protein, Xanthan Gum, Glucosamine HCL, Disodium Succinate, Fisetin, Raspberry Ketone, Sodium Benzoate, Citric Acid, Potassium Sorbate, Arctium Majus Root Extract, Panax Ginseng Root Extract, Biotin. *OS-01 Peptide.”

Several familiar ingredients are present here, including niacinamide, calcium pantothenate, zinc gluconate, raspberry ketone, ginseng, fisetin, and biotin.

- Niacinamide: Research shows that it may help protect hair follicle cells from oxidative stres, reduce the expression of DKK-1 (a protein that promotes hair follicle regression), and prolong the anagen (growth) phase of hair follicles.[2]Choi, Y-H., Shin, J.Y., Kim, J., Kang, N-G., Lee, S. (2021). Niacinamide down-regulates the expression of DKK-1 and protects cells from oxidative stress in cultured human dermal papilla cells. … Continue reading Clinical studies have demonstrated increased hair fullness and thickness in some participants using niacinamide derivatives, though it is thought that it doesn’t actually increase hair density.[3]Draelos, Z.D., Jacobson, E.L., Kim, H., Kim, M., Jacobson, M.K. (2005). A pilot study evaluating the efficacy of topically applied niacin derivatives for treatment of female pattern alopecia. Journal … Continue reading

- Calcium Pantothenate: This ingredient is commonly found in hair care products and supplements. Some studies suggest it may help improve hair thickness and reduce hair loss, especially when combined with zinc. For example, a clinical trial in women found that co-administration of zinc sulfate and calcium pantothenate alone was less pronounced, and more research is needed.[4]Siavash, M., Tavakoli, F., Mokhtari, F. (2017). Comparing the effects of zinc sulfate, calcium pantothenate, their combination and minoxidil solution regimens on controlling hair loss in women: a … Continue reading

- Raspberry Ketone: This has been studied in small human trials and animal models. Topical application promoted hair growth in about 50% of humans with alopecia, possibly by increasing dermal IGF-1 production through sensory neuron activation.[5]Harada, N., Okajima, K., Narimatsu, N., Kurihara, H., Nakagata, N. (2008). Effect of topical application of raspberry ketone on dermal production of insulin-like growth factor-I in mice and on hair … Continue reading However, the evidence base remains limited, and larger studies are necessary to confirm these effects.