- About

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Education.

Prioritize knowledge. Make better choices.

- Evidence.

Sort good studies from the bad.

- Regrowth.

Get bigger hair gains.

Team MembersPhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Rob English

Founder, researcher, & consumer advocate

- Research Team

Our team of PhD’s, researchers, & more

Editorial PolicyDiscover how we conduct our research.

ContactHave questions? Contact us.

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- — Jenna, 31, U.S.A.

I have attached my before and afters of my progress since joining this group...

- — Tom, 30, U.K.

I’m convinced I’ve recovered to probably the hairline I had 3 years ago. Super stoked…

- — Rabih, 30’s, U.S.A.

My friends actually told me, “Your hairline improved. Your hair looks thicker...

- — RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A.

I also feel my hair has a different texture to it now…

- — Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA

Firstly thank you for your work in this field. I am immensely grateful that...

- — Ben M., U.S.A

I just wanted to thank you for all your research, for introducing me to this method...

- — Raul, 50, Spain

To be honest I am having fun with all this and I still don’t know how much...

- — Lisa, 52, U.S.

I see a massive amount of regrowth that is all less than about 8 cm long...

Client Testimonials150+ member experiences.

Scroll Down

Popular Treatments- Treatments

Popular treatments. But do they work?

- Finasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Dutasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Mesotherapy

- Minoxidil

- Oral

- Topical

- Ketoconazole

- Shampoo

- Topical

- Low-Level Laser Therapy

- Therapy

- Microneedling

- Therapy

- Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy (PRP)

- Therapy

- Scalp Massages

- Therapy

More

IngredientsTop-selling ingredients, quantified.

- Saw Palmetto

- Redensyl

- Melatonin

- Caffeine

- Biotin

- Rosemary Oil

- Lilac Stem Cells

- Hydrolyzed Wheat Protein

- Sodium Lauryl Sulfate

More

ProductsThe truth about hair loss "best sellers".

- Minoxidil Tablets

Xyon Health

- Finasteride

Strut Health

- Hair Growth Supplements

Happy Head

- REVITA Tablets for Hair Growth Support

DS Laboratories

- FoliGROWTH Ultimate Hair Neutraceutical

Advanced Trichology

- Enhance Hair Density Serum

Fully Vital

- Topical Finasteride and Minoxidil

Xyon Health

- HairOmega Foaming Hair Growth Serum

DrFormulas

- Bio-Cleansing Shampoo

Revivogen MD

more

Key MetricsStandardized rubrics to evaluate all treatments.

- Evidence Quality

Is this treatment well studied?

- Regrowth Potential

How much regrowth can you expect?

- Long-Term Viability

Is this treatment safe & sustainable?

Free Research- Free Resources

Apps, tools, guides, freebies, & more.

- Free CalculatorTopical Finasteride Calculator

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: What Causes Hair Loss?

- Free ResourceFree Guide: Standardized Scalp Massages

- Free Course7-Day Hair Loss Email Course

- Free DatabaseIngredients Database

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: Hair Loss Disorders

- Free DatabaseTreatment Guides

- Free Lab TestsProduct Lab Tests: Purity & Potency

- Free Video & Write-upEvidence Quality Masterclass

- Free Interactive GuideDermatology Appointment Guide

More

Articles100+ free articles.

-

Hims Hair Growth Reviews: The Pros, Cons, and Real Results

-

Topical Finasteride Before and After: Real Case Studies

-

How to Reduce the Risk of Finasteride Side Effects

-

10 Best DHT-Blocking Shampoos

-

Best Minoxidil for Men: Top Picks for 2026

-

7 Best Oils for Hair Growth

-

Switching From Finasteride to Dutasteride

-

Best Minoxidil for Women: Top 6 Brands of 2026

PublicationsOur team’s peer-reviewed studies.

- Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review

- Use of Botulinum Toxin for Androgenic Alopecia: A Systematic Review

- Conflicting Reports Regarding the Histopathological Features of Androgenic Alopecia

- Self-Assessments of Standardized Scalp Massages for Androgenic Alopecia: Survey Results

- A Hypothetical Pathogenesis Model For Androgenic Alopecia:Clarifying The Dihydrotestosterone Paradox And Rate-Limiting Recovery Factors

Menu- AboutAbout

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Team Members

PhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Editorial Policy

Discover how we conduct our research.

- Contact

Have questions? Contact us.

- Before-Afters

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- Client Testimonials

Read the experiences of members

Before-Afters/ Client Testimonials- Popular Treatments

-

Articles

Anyone searching “How to reverse hair loss online” has undoubtedly come across the Big Three protocol: minoxidil (Rogaine®), finasteride (Propecia®), and ketoconazole shampoo (Nizoral®).

What many might not know: despite ketoconazole’s popularity, it’s not actually FDA-approved for pattern hair loss, nor is it as well-researched as minoxidil or finasteride.

In fact, there are just a few human studies on Nizoral for hair loss and even fewer on people with just androgenic alopecia, the most common form of hair thinning in men.

Interested in Topical Finasteride?

Low-dose & full-strength finasteride available, if prescribed*

Take the next step in your hair regrowth journey. Get started today with a provider who can prescribe a topical solution tailored for you.

*Only available in the U.S. Prescriptions not guaranteed. Restrictions apply. Off-label products are not endorsed by the FDA.

Is Ketoconazole Worthy of Big Three Status?

Here we’ll uncover the evidence on ketoconazole for hair regrowth. We’ll cut straight-to-the-facts about ketoconazole, its effects on hair loss, and whether or not this shampoo is a good fit. Along the way, we”ll also uncover…

- Which formulation is better: 1% or 2% ketoconazole

- Why not everyone is a good candidate for ketoconazole

- How to (potentially) increase ketoconazole’s efficacy (see our before-after photos)

- Who needs to worry about ketoconazole’s potential side effects

Nizoral for Hair Loss: Overview

- Effort: Low (used as shampoo just 2-3 times per week)

- Expectations: According to studies so far, hair loss improvement is observed after 3-6 months

- Response rate: 80%+

- Regrowth rate: ~5% alone; 25-40% if combined with microneedling and/or finasteride and/or minoxidil

- Cost: Low ($10-$20 per bottle of 100ml, which should last two months)

- Problems: Not as well-studied as finasteride or minoxidil; 2% formulations work better but generally require a prescription (though this can be circumvented online); less studied on women (though it’s likely just as effective)

Key Takeaways

Ketoconazole is a low-cost, low-effort shampoo with practically no side effects. It’s clinically shown to help improve hair loss from both androgenic alopecia (AGA) and telogen effluvium (TE).

While 1% ketoconazole is available over the counter, 2% ketoconazole usually requires a doctor’s prescription. Studies show that 2% ketoconazole is more effective, particularly in helping to normalize excessive hair shedding from rapid-onset AGA and/or TE. [1]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9669136/

Can Nizoral help with hair growth?

If a 2% prescription-strength formulation is used, yes.

By itself, ketoconazole is unlikely to stimulate hair regrowth on par with finasteride or combination therapies. So, ketoconazole is just one part of a multi-pronged hair loss regimen. This shampoo may have synergistic effects with stimulation-based therapies like microneedling, massaging, and/or platelet-rich plasma therapy. It also seems to pair well with most FDA-approved / FDA-cleared treatments like finasteride, minoxidil, and low-level laser therapy.

While oral ketoconazole comes with significant risks of side effects, 2% ketoconazole shampoo seems to carry little (if any) risks of side effects – mainly because of its low time of exposure and systemic absorption versus its oral formulations.

The best candidates for 2% ketoconazole shampoo are hair loss sufferers who are comfortable using the shampoo 2-3 times per week and who are dealing with dandruff and/or excessive hair shedding from AGA or TE.

More information on the science behind ketoconazole – its mechanisms of action, supporting evidence, expectations for hair regrowth, and contraindications – can be found below.

What Is Ketoconazole?

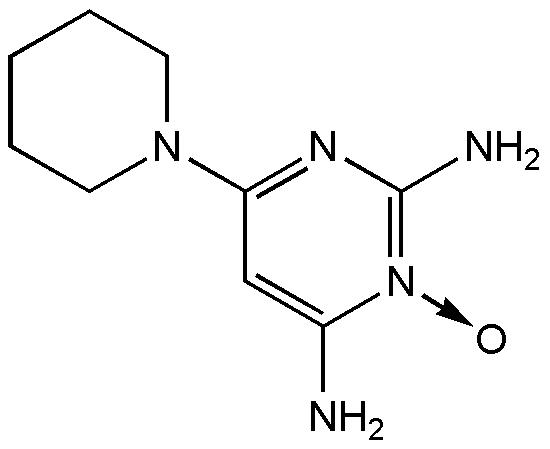

Ketoconazole: molecular structure

Ketoconazole is more commonly mentioned by the brand name Nizoral®, and most people know about it as a shampoo.

Simply put, ketoconazole is an anti-fungal medication. It’s a drug commonly used to help improve fungal-related conditions – like dandruff, fungal infections, certain hormone-linked diseases, and even hair loss from fungal and non-fungal causes.

If it’s a fungal medication, why is it used for hair loss?

Because ketoconazole’s mechanisms of action – as an anti-fungal, anti-inflammatory, anti-androgenic, and pro-anagen agent – all overlap with the causes of telogen effluvium and androgenic alopecia.

Here’s how.

Ketoconazole’s anti-fungal properties help fight off yeast, fungi, and bacterial infections that can cause excessive hair shedding.

As an anti-fungal medication, ketoconazole may also have anti-inflammatory effects, especially in hair follicle sites.[2]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9669136

Many yeast, fungi, and bacteria feed off our dead skin as well as the oils our skin produces (i.e., sebum) which helps to lubricate our hair. Resultantly, these species can often be found residing in parts of our hair follicle – specifically, the infundibulum (i.e., the upper third of each hair shaft) and sebaceous glands.

However, sometimes too many yeast, fungi, and/or bacteria may colonize our sebaceous glands – leading to over-colonization. This is particularly true with the fungus-like yeast species Malassezia spp., which is found in 65% of healthy scalps.[3]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4367942/

Many of these species produce toxic byproducts (i.e. porphyrins) as part of their digestion of sebum. In cases of over-colonization, the accumulation of toxins elicits an inflammatory response in the sebaceous gland. Ironically, the body often responds by sending more sebum to the sebaceous glands – which would help to otherwise resolve the inflammation, but not in these instances. Rather, the excess sebum simply feeds these pathogenic microorganisms, and the process continues.

This is known as a sebum-feedback loop. At moderate levels, it leads to excessive dandruff. At higher levels, it triggers excessive hair shedding – often characterized as microorganism-driven telogen effluvium (TE).

Enter ketoconazole – a potent anti-fungal medication that can help kill off these pathogens and, in doing so, stop this feedback loop.

Ketoconazole damages the cell membranes of fungi and yeast.[4]https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Ketoconazole Specifically, it stops a fungus from producing ergosterol – a crucial part of the cell membrane that helps keep cellular content from leaking out as well as unwelcome substances from invading.

The end result?

Ketoconazole helps kill off pathogenic yeast/fungi, which then reduces scalp inflammation and helps resolve any excessive hair shedding (TE).

This is also why ketoconazole is such an effective treatment for scalp conditions caused by fungi – like dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis. Those conditions are also often caused by Malassezia spp. – the fungus-like yeast that is (fortunately) hypersensitive to ketoconazole.

Ketoconazole might help reduce inflammation in 30-50% of men with androgenic alopecia

Research shows that 30-50% of hair loss sufferers with androgenic alopecia (AGA) also have P. acnes and/or Malassezia spp. infections in the scalp. Just like with TE, the presence of these microbes may exacerbate inflammation, induce early hair shedding, and thereby accelerate the progression of AGA.

In these cases, anti-fungal and/or antibacterial shampoos tend to be useful – because they help to reduce the infections that are accelerating hair shedding in AGA.

Ketoconazole might have anti-androgenic effects in scalp tissues

Ketoconazole isn’t just an anti-fungal; it also has anti-androgenic properties when taken orally. And, while researchers have debated whether these findings extend to topically applied ketoconazole, at least one peer-reviewed paper makes a strong argument in its favor.

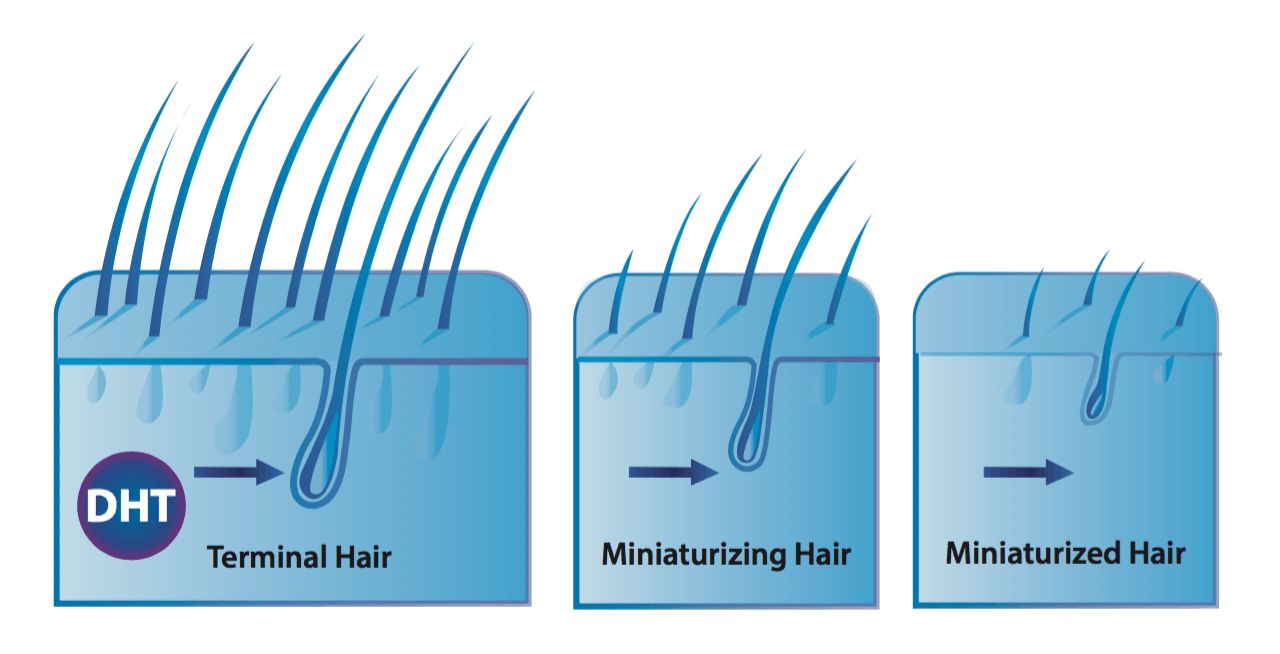

Specifically, this hypothetical model argues that topically applied ketoconazole has anti-androgenic properties.[5]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14729013 In particular, it may help reduce dihydrotestosterone (DHT) – the main hormone implicated in AGA – and in two ways:

- Inhibits 5-alpha reductase. This is an enzyme that converts free testosterone into DHT.

- Blocks androgen receptors. Androgen receptors are where DHT attaches to a cell to influence tissue function (i.e., hair follicle miniaturization). If androgen receptors are blocked, DHT cannot bind to these cells, and thus does not affect that tissue’s functionality.

Together, if ketoconazole has enough of a DHT-reducing effect in balding scalp tissues, it should help to improve AGA – similar to the ways in which treatments like finasteride work.

Ketoconazole may prolong the anagen phase of the hair growth cycle

At any given moment, roughly 85% of scalp hairs are in their growth (anagen) phase, while remaining hairs are either in a resting (catagen) or shedding (telogen) phase.

One defining characteristic of telogen effluvium (TE) is a large increase in the number of shedding versus growth phase hairs (i.e., increased telogen:anagen ratio). In TE, it’s not uncommon to see telogen:anagen ratios of 40-50% and beyond.

This is also observed in androgenic alopecia (AGA) – though to a lesser degree, as AGA is characterized more so by hair follicle miniaturization, less so by hair shedding.

Interestingly, one research team demonstrated that, for reasons unknown, ketoconazole appears to prolong the anagen (growth) phase of hair follicles affected by TE and/or AGA.[6]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18498517

This effect should help delay the progression of both conditions, and maybe even partially reverse them.

Summary of Mechanisms

Ketoconazole might improve telogen effluvium by:

- Killing off pathogens in the scalp, thus normalizing excessive hair shedding triggered by microorganism-mediated inflammation

- Prolonging the anagen phase of the hair cycle

Ketoconazole might improve androgenic alopecia by:

- Killing off pathogens in the scalp, thus normalizing excessive hair shedding triggered by microorganism-mediated inflammation

- Reducing scalp DHT levels by inhibiting 5-alpha reductase and blocking androgen receptors

- Prolonging the anagen phase of the hair cycle

Altogether, these mechanisms suggest that ketoconazole may improve both TE and AGA. So, what’s the evidence in human studies?

Clinical studies: is ketoconazole effective for hair loss?

As is always the case with hair loss research, context is key. And when looking into the effectiveness of ketoconazole, we need to evaluate all clinical studies with several things in mind:

- Was the ketoconazole tested on androgenic alopecia or other hair loss disorders?

- Was the formulation strength 1% or 2%?

- What, exactly, was measured?

To date, there are only four clinical studies on ketoconazole and hair loss (that we could find). As such, we’ll present them in detail. If you’d like, you can skip to the summaries of each study.

Ketoconazole Shampoo: Effect of Long-Term Use in Androgenic Alopecia

Full text: Piérard-Franchimont et al., 1998 [7]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9669136

Study one: 2% ketoconazole versus a normal shampoo

- Who: 39 male only-AGA-subjects

- What: 2% ketoconazole shampoo versus a normal shampoo. During the study duration, 27 men used ketoconazole while 12 men used normal shampoo. There were also 22 non-AGA-controls – half of them testing ketoconazole; half of them trying normal shampoo.

- How long: 2-4 times per week for 21 months

- Measurement: AGA pilary index (PI). This was defined as the percentage of hairs in anagen (A) x average diameter (D, μm) of the hair shafts 1.5 cm from the hair bulb.

- Results:

- PI of non-AGA-controls remained unchanged, no matter the type of shampoo used (ketoconazole versus normal shampoo).

- PI of only-AGA-subjects with unmedicated shampoo showed a slow linear decrease over time, while the ketoconazole group “yielded a progressive PI increase that became evident after a 6-month survey and apparently reached a plateau value after about 15 months”.

- Takeaways:

- In men without androgenic alopecia, ketoconazole doesn’t improve anagen hair counts or hair shaft diameter

- In men with androgenic alopecia, ketoconazole improves both anagen hair counts and overall hair shaft diameter

Study two: 2% ketoconazole versus 2% minoxidil

- Who: 8 male only-AGA-subjects; 4 using ketoconazole, and 4 using minoxidil

- What: 2% ketoconazole shampoo (vs. 2% minoxidil lotion)

- How long: ad libitum (i.e., as often as desired) for 6 months

- Measurements: hair density; hair shaft diameter and the corresponding sebaceous gland

- Results:

- “A 7% increase in the median hair shaft diameter was yielded by both the [ketoconazole] shampoo and minoxidil + unmedicated shampoo combination.”

- “A 19.4% decrease in the mean sebaceous gland area was observed in the [ketoconazole] group. In contrast, the same variable increased by 5.3% in the minoxidil + unmedicated shampoo group.”

- Ketoconazole improved density of hair by 18% compared to minoxidil by 11%.

- Takeaways:

- Ketoconazole increases hair shaft diameter by 7%, similar to minoxidil

- Ketoconazole decreases sebaceous gland size by nearly 20% – possibly due to its anti-fungal effects. In other words, ketoconazole kills off pathogens that over-colonize, and thereby over-enlarge, the sebaceous glands. This was unique to ketoconazole (minoxidil did not have this effect).

- Ketoconazole improves hair density nearly twice as well as minoxidil

Key points:

These studies are all on men with AGA only, all of whom tested 2% ketoconazole as a shampoo.

The results all show significant improvements to hair density, as well as prolonged anagen phases and hair diameter. Moreover, one study also found that ketoconazole decreased sebaceous gland size – most likely a result of its ability to kill off pathogens overcrowding those sebaceous glands. For these reasons, it’s not unreasonable to assume that ketoconazole might also decrease sebum output.

Nudging hair shedding by antidandruff shampoos. A comparison of 1% ketoconazole, 1% piroctone olamine, and 1% zinc pyrithione formulations

Full text: Piérard-Franchimont et al., 2002 [8]https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1467-2494.2002.00145.x

- Who: 150 men presenting with telogen effluvium related to androgenic alopecia associated with dandruff, separated into three groups with different shampoos: 50 men on 1% ketoconazole, 50 on 1% piroctone olamine, and 50 on 1% zinc pyrithione

- What: 1% ketoconazole shampoo versus two other anti-dandruff shampoos

- How long: 2-3 times a week, for 6 months

- Measurements: hair shedding, hair density, anagen hair percentage, mean proximal hair shaft diameter, sebum excretion rates

- Results:

- Pruritus and dandruff cleared rapidly in all three shampoo groups

- Hair density remained unchanged in all three shampoo groups

- Hair shedding decreased by 17.3% in the ketoconazole group, 16.5% in the piroctone olamine group, and 10.1% in the zinc pyrithione group

- Anagen hair ratio increased by 4.9% in the ketoconazole group, 7.9% in the piroctone olamine group, and 6.8% in the zinc pyrithione group

- Sebum excretion rate decreased by 4.8% in the ketoconazole group, 2.9% in the piroctone olamine group, and 5.5% in the zinc pyrithione group

Key points:

The men featured in this study have telogen effluvium and androgenic alopecia. And, encouragingly, it seems like 1% ketoconazole shampoo 2-3 times per week lessened hair shedding by ~20%, increased hair shaft thickness by ~5%, and decreased sebum output by ~5%.

The bottom-line: comparing across studies, 1% ketoconazole isn’t as impressive as 2%, but the results are still there. For men (and women) suffering from both TE and AGA, 1% or 2% ketoconazole might be a great intervention (among other treatments).

Comparative Efficacy of Various Treatment Regimens for Androgenetic Alopecia in Men

Full text: Khandpur et al., 2002 [9]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12227482

- Who: 100 male only-AGA-subjects randomized into four groups:

- 30 finasteride

- 36 finasteride + minoxidil

- 24 minoxidil

- 10 finasteride + ketoconazole

- What: 2% ketoconazole shampoo + finasteride 1mg oral/day (vs. finasteride vs. finasteride + 2% minoxidil vs. 2% minoxidil)

- How long: 3 times a week for 1 year

- Measurements: patients’ self-assessment and physicians’ assessment. Photographs were taken.

- Results: finasteride + minoxidil and finasteride + ketoconazole reap the best improvement scores for both self- and physician-assessments. However, finasteride + minoxidil slightly outperformed finasteride + ketoconazole.

Key points:

2% ketoconazole works well as a combination therapy with finasteride.Pilot Study of 15 Patients Receiving a New Treatment Regimen for Androgenic Alopecia: The Effects of Atopy on AGA

Full text: A.W. Rafi et al., 2011 [10]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22363845

- Who: 15 AGA subjects with either atopic dermatitis or seborrheic dermatitis

- What: 2% ketoconazole shampoo. 8 subjects used NuH Hair + finasteride + minoxidil + ketoconazole, 5 using only NuH Hair, 1 using NuH Hair + finasteride + ketoconazole, 1 using NuH Hair + ketoconazole (a subject with seborrheic dermatitis)

- How long: ketoconazole usage 2-3 times a week for 9 months

Measurements: Average time for hair regrowth, photo and investigator assessments - Results:

- Average time for hair regrowth

- 30 days with NuH Hair + finasteride + minoxidil + ketoconazole

- 30 days with NuH Hair + finasteride + ketoconazole

- 60 days with NuH Hair + ketoconazole

- 90 days with NuH Hair alone

- Average time for hair regrowth

Key points:

Ketoconazole works well as a combination therapy with finasteride and minoxidil, and it can also improve AGA even in men with atopic and/or seborrheic dermatitis.Key points summary of clinical trials

- By itself and as a combination therapy, 2% ketoconazole improves AGA and TE by:

- Increasing anagen (growth) hairs

- Increasing hair shaft diameter

- Increasing hair density

- Hair improvements from 2% ketoconazole seem to sustain, not wane (at least over 21 months of use)

- 2% ketoconazole increases hair density; 1% ketoconazole doesn’t

Very broadly speaking, ketoconazole alone might be a little bit less effective than minoxidil alone, but it also seems to be a better bet in some respects: more people respond to Nizoral for hair loss, its effects don’t wane over 21 months, and it targets AGA from multiple angles.

Applying Ketoconazole

If you want to get the most out of ketoconazole, here are some tips to maximize your chances of hair regrowth and use ketoconazole in the most effective way:

Opt for 2% prescription, not 1% over-the-counter

There is evidence that prescription-strength 2% ketoconazole is (much) more effective than 1 % ketoconazole.

In this study, 2% ketoconazole shampoo increased hair density by 18% while in this study, 1% ketoconazole shampoo didn’t change hair density at all. Both times, ketoconazole was applied around 3 times a week for 6 months. [11]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9669136 [12]https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1467-2494.2002.00145.x

Also, in this study, 1% ketoconazole and 2% ketoconazole were compared with their effect on seborrheic dermatitis, and the results were so that “[ketoconazole] 2% had superior efficacy compared to [ketozonaole] 1% in the treatment of severe dandruff and scalp seborrheic dermatitis.”[13]https://www.karger.com/Article/PDF/51628

So get the 2% ketoconazole, not the 1%.

How can I get the 2% Nizoral shampoo without a prescription?

One of our members found 2% ketoconazole online, and from a company called Nizoral Shop.

So how does this company was circumventing prescriptions and shipping to the U.S. (and elsewhere)?

As it turns out, their Nizoral products depart from overseas warehouses where prescriptions are not required.

So, for anyone looking for 2%, Nizoral Shop might be a great option. The company later offered our members a 20% discount on the first 100 orders from our community.

To access case studies, expert interviews, forums, comprehensive guides, and other special offers, join our membership. You will also get a personalized Regrowth Roadmap tailored to your needs and treatment preferences.

We aren’t affiliated with any physical product brands, and we haven’t tried this shampoo brand. The company did say that for anyone making orders during the COVID-19 period: “It is highly recommended to select UPS/DHL priority express shipping option, as the other shipping methods are suspended until further notice due to the current pandemic.”

Get the Nizoral shampoo, not the topical

This is just a practical tip. In some countries, there is a topical version of ketoconazole available to consumers. Arguably, as a topical, ketoconazole would likely have more significant effects versus a shampoo – mainly because of the differences in the length of time on the scalp.

At the same time, topical ketoconazole may be more likely to cause side effects due to higher systemic absorption. What’s more, the topical non-shampoo version of ketoconazole has never been used in human studies on hair loss.

So, we recommend sticking to what’s studied; not what’s theoretically potentially more effective. Go with Nizoral shampoo.

Apply 2-4 times per week

Collectively, these studies show that applying 2% ketoconazole 2-3 times per week seems to show the most promise at resolving hair loss disorders and not just dandruff. So, plan on using this shampoo around every other day.

Do I have to use it forever?

Not necessarily. If ketoconazole’s most beneficial mechanism of action is that it kills off the over-colonization of pathogenic organisms that are creating additional scalp inflammation, then chances are that after these pathogenic organisms are gone, you may be able to significantly reduce usage frequencies after months 3-4.

That means transitioning to once-weekly usage (or less).

Combine ketoconazole with other hair loss therapies and treatments

Generally speaking, in ketoconazole studies on humans with AGA, the best results have been achieved by those that used ketoconazole in combination with other treatments.

This makes sense, as ketoconazole’s mechanisms of action are different from minoxidil, which are different from microneedling, which are different from finasteride. The more mechanisms you target, the better your results (in most cases).

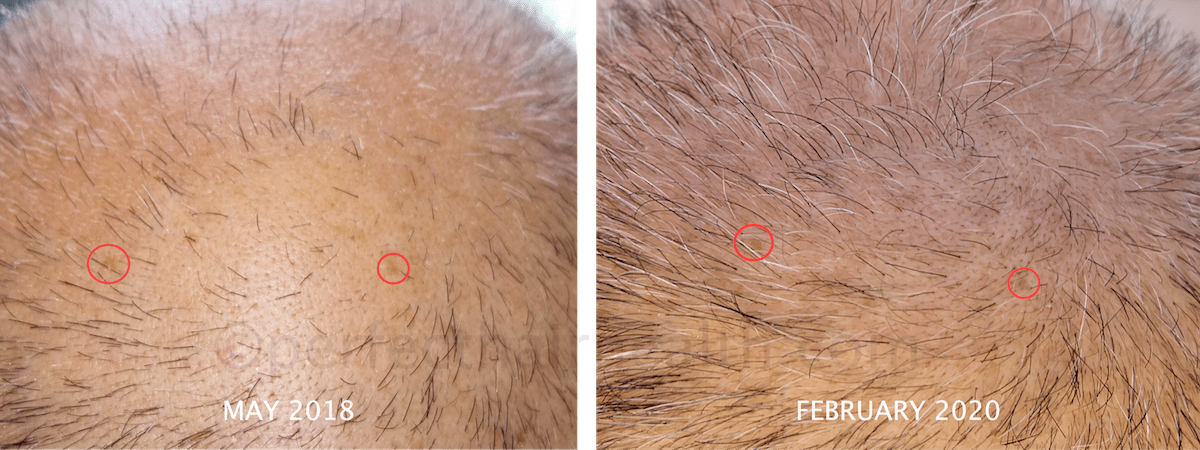

In fact, we have an example from our community of a member doing just this: combining ketoconazole with microneedling, massaging, and minoxidil to break through a period of stagnation in hair recovery.

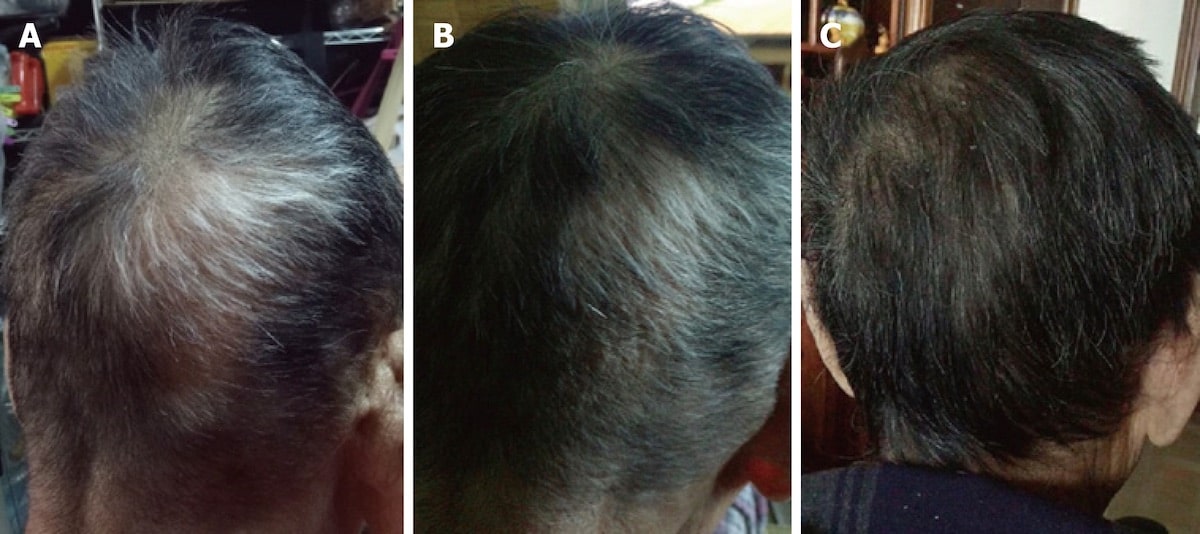

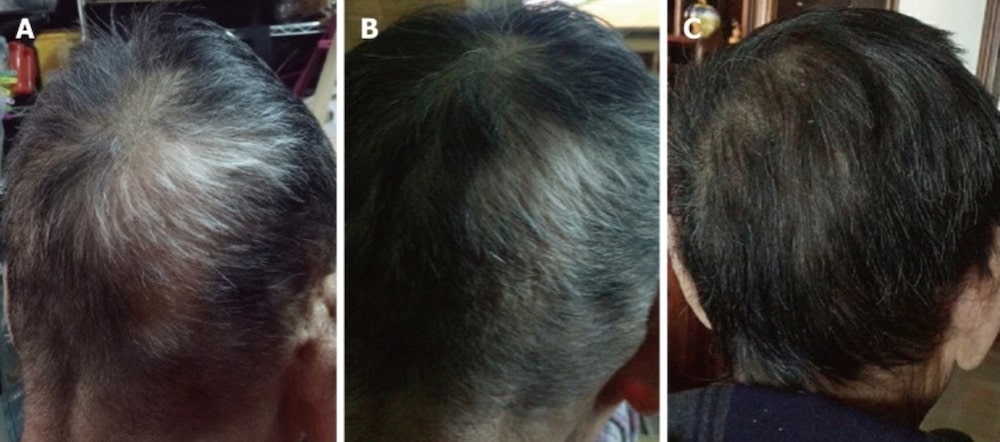

Here are his results: 20+ months of scalp massage alongside microneedling, minoxidil, and ketoconazole

Hair growth from scalp massage alongside microneedling, minoxidil, and ketoconazole

Nizoral for Hair Loss: The Side Effects

This study showed that high doses of oral ketoconazole can impair testosterone production in men, but this review article from drugs.com states that these effects haven’t been reported – even with topical ketoconazole – and seem unlikely anyway because through topical application, way too little substance is absorbed.[14]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3659003[15]https://www.drugs.com/monograph/ketoconazole-topical.html

So, based on this information, you don’t need to worry about the shampoo’s effect on testosterone.

Rare side effects are summarized here. These are not prevalent, particularly if ketoconazole is formulated as a shampoo.[16]https://www.drugs.com/sfx/ketoconazole-topical-side-effects.html

All in all, ketoconazole shampoo seems to be relatively free of side effects, and a relatively safe option for those with excessive hair shedding from androgenic alopecia, telogen effluvium, or both.

For those with sensitive skin who wish to try a more natural Nizoral formulation, Sent from Earth Caffeine & Saw Palmetto Shampoo may suffice. However, this shampoo contains just 1% ketoconazole. We are not affiliated with this company; we just wanted to provide an example of what else is out there.

Who are the best candidates for Nizoral?

In regard to hair loss sufferers, ketoconazole is proven to help:

Those with androgenic alopecia

Having checked the studies above, it is pretty indisputable that ketoconazole improves AGA in humans – and not only in those who suffer additionally from seborrheic dermatitis or telogen effluvium, but clearly also in those who have only AGA. [17]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9669136

Those with a hair shedding disorder (like telogen effluvium)

When TE is derived from a pathogenic microorganism, seborrheic dermatitis, or both (which can be the case), ketoconazole might help – as its anti-fungal effects can intervene in the earliest stages of seborrheic dermatitis development.[18]https://donovanmedical.com/hair-blog/2017/5/23/is-it-possible-for-seb-derm-to-cause-hair-loss

Interestingly, ketoconazole seems to improve TE regardless of its causes. We know this from the above study with 150 TE men, which showed that ketoconazole improved TE outcomes – despite the high likelihood of myriad TE causes present within that study.[19]https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1467-2494.2002.00145.x

These studies are mostly on men. What about women?

To our knowledge, there are no published studies on Nizoral for hair loss in females with pattern alopecia (yet). However, one study on females found that 2% ketoconazole as a topical (not shampoo) demonstrated similar efficacy compared to 2% minoxidil over six months of use.[20]https://biomeddermatol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41702-019-0046-y

Given the results of this study (and ketoconazole’s suspected mechanisms of action), there is reason to believe ketoconazole shampoo is probably effective for women, as well.[21]https://www.derm.theclinics.com/article/S0733-8635(12)00093-9/abstract

You’re an ideal candidate for ketoconazole if you…

- Suffer from AGA and/or a hair shedding disorder, particularly alongside seborrheic dermatitis or symptoms of microorganism overgrowths (like excessive dandruff and/or sebum activity)

- Want the benefit of a chemical treatment without a high risk of severe side effects

- Are using minoxidil/finasteride and want to increase their efficacy

- Are performing stimulation-based therapies (i.e., massaging, microneedling, and/or platelet-rich plasma) and want to speed up the regrowth process.

Who is not a good candidate for ketoconazole?

Ketoconazole is less researched on women, although that doesn’t make it less effective. But there are contraindications for oral ketoconazole in pregnant women – and, as a precaution, the standard recommendation is for all women who intend on getting pregnant to avoid even the topical formulations.[22]https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/ketoconazole.html

Regarding mothers who breastfeed, ketoconazole use is generally considered acceptable, but caution is recommended.[23]https://www.drugs.com/breastfeeding/ketoconazole.html

Above all, both men and women are strongly advised against the use of oral ketoconazole for the treatment of AGA/pattern hair loss. While topical/shampoo formulations have a strong safety profile, oral ketoconazole doesn’t. Consequently, it comes with a higher risk of side effects and is even banned from sale in certain countries.

Summary

Ketoconazole isn’t as well-researched as minoxidil or finasteride. However, studies show that it might be an effective add-on treatment for hair loss (specifically, androgenic alopecia).

There’s evidence that ketoconazole is almost as effective as minoxidil (Rogaine®) at increasing hair density… and that it might be particularly helpful for those with pattern hair loss with rapid hair shedding (i.e., telogen effluvium). So, if you fit within these categories, you might want to consider trying it.

Having said that, ketoconazole formulation matters. While 1% over-the-counter ketoconazole might help reduce dandruff and improve hair loss, 2% prescription ketoconazole is likely superior in its ability to improve hair loss outcomes. So, if you’re going to commit to Nizoral for hair loss, commit fully. Visit your doctor and get a prescription. Or, order online from the Nizoral Shop. Then, start shampooing.

References[+]

References ↑1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9669136/ ↑2, ↑7, ↑11, ↑17 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9669136 ↑3 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4367942/ ↑4 https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Ketoconazole ↑5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14729013 ↑6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18498517 ↑8, ↑12, ↑19 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1467-2494.2002.00145.x ↑9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12227482 ↑10 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22363845 ↑13 https://www.karger.com/Article/PDF/51628 ↑14 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3659003 ↑15 https://www.drugs.com/monograph/ketoconazole-topical.html ↑16 https://www.drugs.com/sfx/ketoconazole-topical-side-effects.html ↑18 https://donovanmedical.com/hair-blog/2017/5/23/is-it-possible-for-seb-derm-to-cause-hair-loss ↑20 https://biomeddermatol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41702-019-0046-y ↑21 https://www.derm.theclinics.com/article/S0733-8635(12)00093-9/abstract ↑22 https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/ketoconazole.html ↑23 https://www.drugs.com/breastfeeding/ketoconazole.html Studies show that within 3-6 months of stopping minoxidil, any hair growth resulting from the drug is lost. After quitting minoxidil, hair counts can even temporarily fall below where they would’ve been had we never sought treatment at all, before eventually rebounding back to baseline.

Why does this happen? Is there a way to lessen the “withdrawal shed” from minoxidil? For those who’ve seen hair gains with minoxidil but prefer not to use it forever, there may be some methods to mitigate shedding after quitting minoxidil. This article explains the evidence, and provides an action plan.

- About Minoxidil

- Why People Stop Taking Minoxidil

- What Happens When Quitting Minoxidil

- Is Minoxidil Plus Microneedling the Answer?

- How to (Possibly) Prevent Shedding After Stopping Minoxidil

Interested in Topical Minoxidil?

High-strength topical minoxidil available, if prescribed*

Take the next step in your hair regrowth journey. Get started today with a provider who can prescribe a topical solution tailored for you.

*Only available in the U.S. Prescriptions not guaranteed. Restrictions apply. Off-label products are not endorsed by the FDA.

About Minoxidil

Minoxidil is an over-the-counter drug approved by the FDA to treat androgenic alopecia. It’s commonly known by the brand name Rogaine. Along with finasteride, minoxidil is one of only two drugs approved to treat androgenic alopecia in both men and women.

Nobody actually knows how minoxidil works. Minoxidil was initially developed in the 1980s as an oral drug to treat high blood pressure. But when patients started reporting “unwanted” hair regrowth after three or more months of use, its manufacturers decided to reformulate it into a topical and begin testing it on men with androgenic alopecia.[1]https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(08)00809-8/abstract

Today, we still aren’t sure how it works. But since side effects are minimal, it was nonetheless approved by the FDA for use. There are two primary hypotheses on the mechanisms behind minoxidil.

Hypothesis 1: Minoxidil is a Vasodilator

One defining characteristic of androgenic alopecia is reduced blood flow to balding regions. While there’s debate over whether reduced blood flow is a consequence or cause of hair loss, it’s undisputed that without proper blood supply to a hair follicle, hair cannot grow.

As a vasodilator, minoxidil widens blood vessels, potentially increasing blood flow to the scalp. In addition, Minoxidil opens potassium ion channels, which some researchers think works alongside vasodilation to improve hair growth.[2]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9395721/

Hypothesis 2: Minoxidil Alters the Hair Growth Cycle

It’s possible that minoxidil kicks miniaturizing hair follicles back into the anagen (growth) phase of the hair cycle. Hairs thus become thicker, giving the appearance of overall improved hair density. This could be the result of minoxidil decreasing prostaglandin D2 levels while boosting other prostaglandins, like prostaglandin E2, to downregulate pro-inflammatory growth factors that are linked to hair shedding.[3]https://www.jidonline.org/article/S0022-202X(15)42806-4/pdf

In addition, Minoxidil may prolong the growth phase of the hair cycle by maintaining beta-catenin activity in dermal papilla cells.[4]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21524889/

How Long Does Minoxidil Take to Work?

Minoxidil’s event horizon is approximately 3-6 months. Over half of the people who try it respond to minoxidil within this time frame. But early results tend to wane over time.

One study found that at six months, men using 5% minoxidil twice-daily saw a near-60% change in hair ‘weight’ in balding regions.[5]https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S019096229970006X In other words, their hair had thickened or regrown to weigh 60% more than it did at the start of the study.

That’s huge.

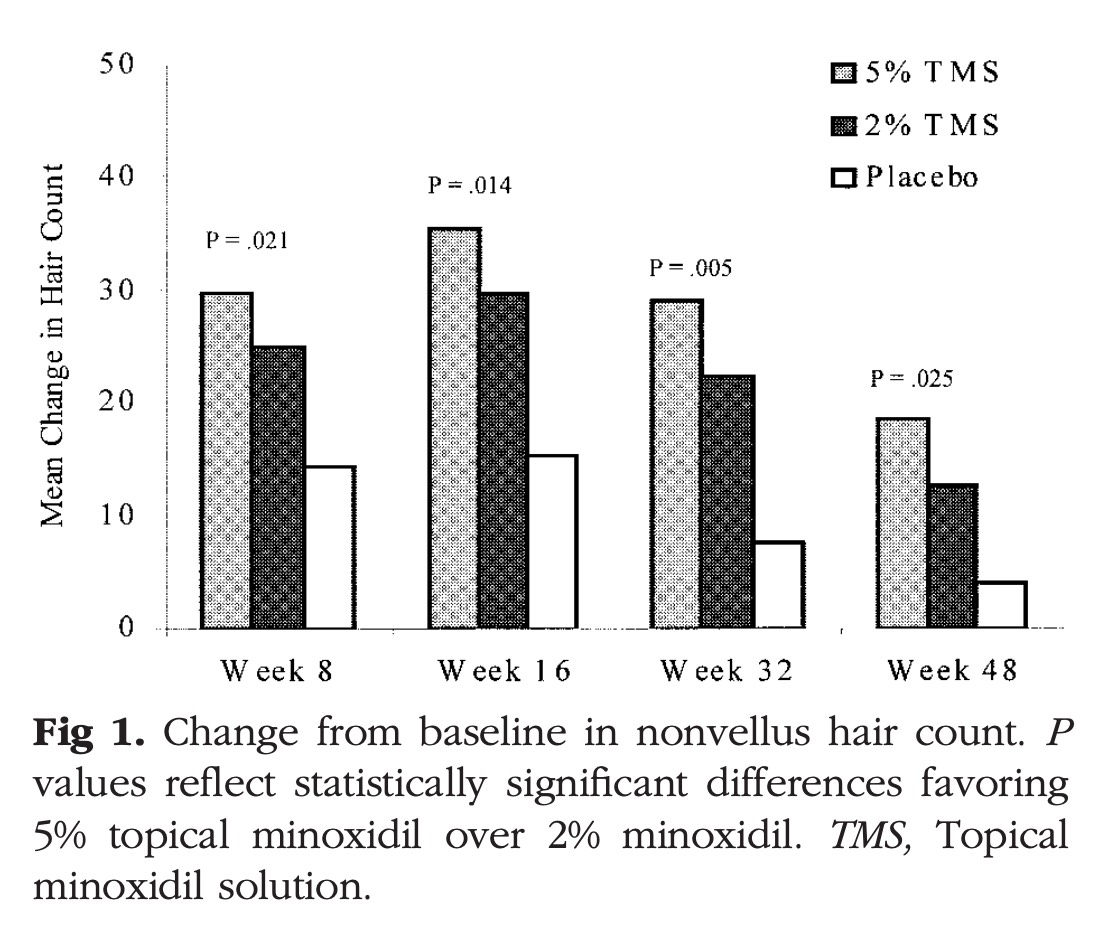

Unfortunately, the same study showed that at 96 weeks, those hair weights decreased to merely 25% higher than baseline. This also happens to be a consistent finding across most studies on minoxidil. Just see this 48-week chart on the effects of 2% and 5% minoxidil on hair counts.[6]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12196747/ Results tend to peak at week 16, then decline thereafter.

Olsen, E. A., Dunlap, F. E., Funicella, T., Koperski, J. A., Swinehart, J. M., Tschen, E. H., & Trancik, R. J. (2002). A randomized clinical trial of 5% topical minoxidil versus 2% topical minoxidil and placebo in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 47(3), 377–385.

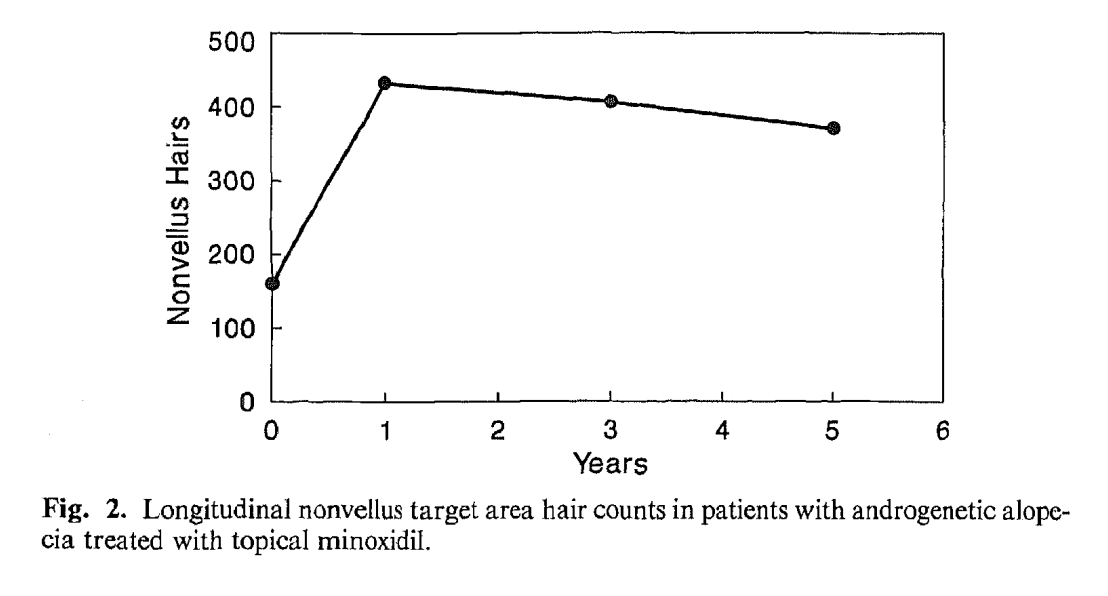

This is echoed on 5-year studies on minoxidil, which show a steady decline in non-vellus hair counts in target areas after year one: [7]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2180995/

Olsen, E. A., Weiner, M. S., Amara, I. A., & DeLong, E. R. (1990). Five-year follow-up of men with androgenetic alopecia treated with topical minoxidil. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 22(4), 643–646.

Somewhat relatedly, other studies have demonstrated greatly increased hair counts that failed to translate to visual improvements in hair density.[8]https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(08)00809-8/abstract

Long-story short: over time, minoxidil’s efficacy begins to wane. And while minoxidil can temporarily increase hair counts, these increases don’t always lead to cosmetic levels of hair regrowth.

Why is this?

Minoxidil helps kickstart hairs back into the anagen (growth) phase of the hair cycle. However, it doesn’t address DHT-driven hair follicle miniaturization. So, while hair counts increase, hair diameters continue to decline, leading to a loss of hair volume and thereby hair thinning over time.

Most people who try minoxidil quit within a year as their results stabilize or slowly decline.

Let’s take a closer look at why, and what happens when they do.

Why Stop Taking Minoxidil?

People who stop taking minoxidil tend to fall into two main camps. Either minoxidil is just not working for them at all, or it is working, but for various reasons, they’d prefer to pass on a twice-daily application for the rest of their lives.

Minoxidil Non-Responders

Some people simply don’t respond to minoxidil. This could be a sign their hair loss stems from a condition other than androgenic alopecia. But as we’ll see, minoxidil just doesn’t always work well on its own.

Is it Androgenic Alopecia?

Non-response to minoxidil could signify that hair loss is not due to androgenic alopecia but something else. There’s some evidence that oral minoxidil might improve hair shedding disorders like chronic telogen effluvium, but it’s technically not FDA-approved for that condition.[9]https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs40257-018-0409-y

Is it Strong Enough?

When choosing between 2% and 5%, choose the more potent formula. Studies show that in men, 5% minoxidil is better than the 2% formula, and the same is likely true for women. Prescriptions are available for concentrations of 10% or 15%, and studies show minoxidil non-responders often see better hair growth after switching to these strengths.[10]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28078868/

Is it in Use as a Monotherapy?

The reality is that minoxidil just isn’t very effective by itself. To understand why it helps to learn about an enzyme called Sulfotransferase.

In order to become active, minoxidil must come into contact with Sulfotransferase. About 40% of balding men just don’t have enough Sulfotransferase to elicit a response to Minoxidil – which happens to closely correspond with the percent of non-responders of minoxidil.

What might help increase Sulfotransferase levels? We’ll get to that later.

The Downsides of Minoxidil

Even minoxidil responders may not want to use it forever. It can be costly and inconvenient, and it does have some minor side effects.

Cost

Monthly minoxidil use costs between $15-$40. Hair loss sufferers will need to try it for 6 months and spend close to $200 just to see if they’re a responder. Stick with it for years, and they could end up spending thousands. Some users find that as their results taper off, it no longer warrants the ongoing expense.

Note: the price of minoxidil can be dramatically reduced by purchasing in bulk and through big brands – like the minoxidil offered from Kirkland. But these formulations tend to come with propylene glycol and other carrier ingredients that can irritate the scalp.

Side Effects

The biggest side effect of minoxidil seems to be skin irritation. Between 2% to 6% of users report this.[11]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221695328_Minoxidil_Use_in_Dermatology_Side_Effects_and_Recent_Patents However, allergy testing suggests that up to 80% of skin-irritation related side effects from minoxidil may not be caused by the minoxidil itself, but rather, a carrier ingredient called propylene glycol.[12]http://www.thaiscience.info/Journals/Article/JMAT/10986429.pdf

There are brands that offer minoxidil without propylene glycol, so be sure to check the labels if you have any concerns of allergies.

Additional side effects include toxicity to cats, under-eye bags, and potential heart palpitations. But these are all relatively rare.

Inconvenience

As hair growth treatments go, minoxidil is relatively easy and convenient. Still, not everyone wants to commit to twice-daily use for the rest of their lives, regardless of its effectiveness. And as we mentioned earlier, minoxidil alone is not an effective long-term treatment. To keep results from waning, using minoxidil in combination with other therapies is recommended, which only adds time and expense.

So if someone decides to stop taking minoxidil, what are the expectations?

What Happens When Stopping Minoxidil

In 1999, researchers conducted a study on the effects of abruptly ceasing minoxidil after long-term treatment.[13]https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(99)70006-X/fulltext Not only did the group who stopped minoxidil shed hair, but for a month or two, they actually crossed below the threshold of where they would have been if they’d never used minoxidil to begin with.

Let’s take a closer look at what happened.

The Study on Stopping Minoxidil

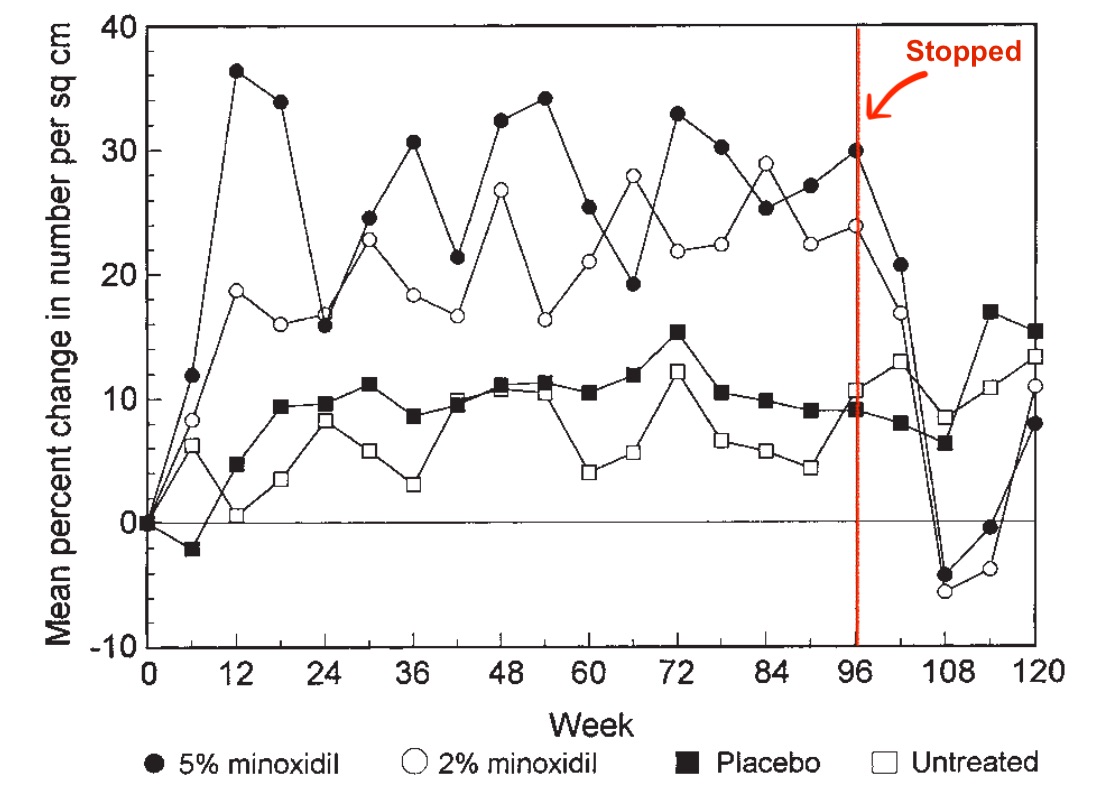

Researchers spent more than two years following four separate cohorts. One group was treated with 2% minoxidil, another group with 5%, one group was given a placebo, and the fourth group did nothing.

Both the 2% and 5% groups saw improvements in hair counts by the three-month mark. As we’ve said, these improvements leveled off a bit from that point forward but were still higher than hair counts in the placebo and control groups.

After almost two years of treatment, at the 96-week mark, the investigators took the people in the 2% and 5% minoxidil groups and discontinued treatment. We can see the exact moment this occurred by looking at the data on hair weights, which soon started decreasing.

Price, V. H., Menefee, E., & Strauss, P. C. (1999). Changes in hair weight and hair count in men with androgenetic alopecia, after application of 5% and 2% topical minoxidil, placebo, or no treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 41(5), 717–721.

Three months later, by week 108, their hair loss had dipped well below the placebo group and below where they were at the start of the study. Another three months after that, by week 120, both the 2% and 5% groups had rebounded to rejoin toss sufferers will end up right where they started.

As mentioned, any excess shedding should not be permanent, as hair will readjust to new homeostasis without the drug.

So the question becomes, is there a method to weaning from minoxidil that can prevent or reduce shedding?

Is Minoxidil Plus Microneedling the Answer?

In the above study, minoxidil was used as a monotherapy. And we know from the research that combining minoxidil with additional therapies, such as microneedling, can improve outcomes for non-responders and may prevent results from waning after the initial 3-6 months of usage.

So could microneedling also prevent (or delay) shedding if one decides to stop taking minoxidil? Let’s investigate what happens when we use these two therapies in tandem.

About Microneedling

Microneedling is a micro-wounding procedure that involves pricking the skin with tiny needles using either a roller or a pen-shaped tool. Studies have shown microneedling elicits growth factors, signaling proteins, and the enzymatic activity of Sulfotransferase, which we referred to earlier.

In some studies, Microneedling plus Minoxidil seems to elicit a fourfold greater effect on hair count increases than Minoxidil alone.[14]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3746236/

In fact, when combining minoxidil with microneedling, new data show that all new hair gains might hold for much longer – even after quitting all treatments.

The Data on Combined Therapies

Let’s take a closer look at a 2020 study to see why microneedling could be the key to maintaining hair growth, even after quitting minoxidil.[15]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29028377/

In the study, researchers split men into 3 groups. One treated their hair loss with minoxidil only, another group with microneedling only, and one group combined the two therapies. As other studies have shown, the combined therapies were significantly more effective in terms of hair growth.

But what the researchers did next was interesting. They stopped all treatments for each of the 3 groups, then brought them in 6 months later to ask, ‘how much hair growth did you retain, even in the absence of treatment?’ Here were their results:

- Minoxidil Only – 90% lost all new hair growth (just 10% retained new growth)

- Microneedling Only – 70% retained some new hair, 20% retained all new hair, 10% lost all new hair

- Combined Therapies – 70% retained some new hair, 20% retained all new hair, 10% lost all new hair

So the group that combined minoxidil with microneedling not only experienced at least twice the hair growth of the other two groups, but 70% of them held on to at least some of this new growth, even after stopping all treatments. And yet, before we conclude that microneedling plus minoxidil is a fail-safe method for maintaining hair growth after treatment ends, there are some possibilities to consider.

- It’s possible if researchers asked the same question 12 months versus 6 months later, all groups would report an equal amount of hair loss. We’ve seen with other therapies, Finasteride for example, that gains disappear over a longer timeline.

- While the number 70% sounds big, the sample size in this study was relatively small. Each group contained just 20 men. So, while it’s great that 14 men maintained at least some of their results for 6 months after treatment ended, it’s possible this percentage could change within a larger sample.

So, while the study above is promising, we don’t really have enough data to definitively say whether or not hair shedding after quitting minoxidil can be prevented.

We’ve yet to see any literature that would help predict who will or will not shed badly from minoxidil. However logically, it may be that those who respond better to minoxidil (or the more hair minoxidil helps one keep during use) simply have more hair to lose during withdrawal.

Anecdotally, about 50% of the male Perfect Hair Health members who have slowly weaned from minoxidil while maintaining microneedling therapy noticed no cosmetic differences in their hair counts afterward.

Basically, they’re able to maintain similar visuals even without the drugs. The other 50% do see a decline visually, but it’s nowhere near baseline or very rarely all the way back to baseline.

If hair loss sufferers do get to a point where they’re happy with their hair and want to wean away from drugs, doing so with the right tapering protocol while continuing the use of microneedling could be a solution.

The Best Way to Quit Minoxidil

When is the best time to call it quits? Never, if you’d like to take as much risk off the table as you can.

Otherwise, the following tips may help minimize any shedding related to minoxidil withdrawals.

- Start microneedling before quitting. Minoxidil and microneedling are synergistic treatments. Try them together for at least 3-6 months before dropping the drug.

- Don’t quit cold turkey. Follow a tapering protocol to minimize abrupt changes to the scalp environment. (We have a detailed weaning protocol in our membership.)

- Continue with alternative treatments. An effective weaning protocol takes up to 6 months. Continue with microneedling during this time.

- Replace minoxidil with natural therapies. Individuals may wish to experiment with other topicals instead, such as 2-5% rosemary oil.

For the most part, minoxidil requires lifelong use to hold onto any hair maintained or regrown. As such, shedding often occurs for 3-6 months following a stop in minoxidil application. But, we can significantly mitigate this shed by combining minoxidil with additional therapies and following a tapering protocol.

Summary

Minoxidil can be an effective treatment for androgenic alopecia, although research says when used alone, results taper off over time. Combining minoxidil with wounding therapies such as microneedling can make it more effective.

When stopping minoxidil, hair loss can be expected. Research shows losses will be greatest within the first 3-6 months of quitting but will eventually rebound to where hair counts would have been had minoxidil never been applied.

This doesn’t mean hair loss sufferers are stuck taking minoxidil for the rest of their lives. The same microneedling therapies that make minoxidil more effective may help sustain results after quitting the drug. This is especially true for those who commit to a strict tapering protocol versus quitting minoxidil cold turkey.

So should people use minoxidil?

For many, it’s worth a try. Some people will see visual improvements, some of which can be maintained with a proper weaning program. In the worst case, people will most likely end up where they would’ve been without treatment, but not worse off.

References[+]

References ↑1 https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(08)00809-8/abstract ↑2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9395721/ ↑3 https://www.jidonline.org/article/S0022-202X(15)42806-4/pdf ↑4 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21524889/ ↑5 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S019096229970006X ↑6 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12196747/ ↑7 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2180995/ ↑8 https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(08)00809-8/abstract ↑9 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs40257-018-0409-y ↑10 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28078868/ ↑11 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/221695328_Minoxidil_Use_in_Dermatology_Side_Effects_and_Recent_Patents ↑12 http://www.thaiscience.info/Journals/Article/JMAT/10986429.pdf ↑13 https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(99)70006-X/fulltext ↑14 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3746236/ ↑15 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29028377/ Minoxidil is just one of two FDA-approved hair loss drugs. But FDA-approval doesn’t necessarily equate to guaranteed results with Minoxidil. In fact, many hair loss sufferers use minoxidil (i.e., Rogaine®) for six months and still don’t see significant benefits.

Why is that? In other words, why do 50% of people seem to respond favorably to minoxidil, while the remaining 50% see little-to-no benefit?

Research suggests this split in regrowth might be tied to an enzyme in the hair follicle called sulfotransferase.

Without coming into contact with sulfotransferase, Minoxidil won’t have an effect, and about 40% of men just don’t have enough sulfotransferase to elicit a response to Minoxidil.

Minoxidil is a pro-drug, meaning it has to be activated before it can exert its effects. Sulfotransferase plays an irreplaceable role in this because it turns minoxidil (its pro-drug form) into minoxidil sulfate (its active form).

We call this a rate-limiting step in the response rate to topical minoxidil, meaning the individual activity of the sulfotransferase enzymes on your scalp will predict your response rate to minoxidil.

This enzyme is also found in the liver. When oral minoxidil is ingested, it passes through these sulfotransferase enzymes, where it’s then distributed to the hair follicles throughout the body.

Interested in Topical Minoxidil?

High-strength topical minoxidil available, if prescribed*

Take the next step in your hair regrowth journey. Get started today with a provider who can prescribe a topical solution tailored for you.

*Only available in the U.S. Prescriptions not guaranteed. Restrictions apply. Off-label products are not endorsed by the FDA.

When Can Responders Expect to See Visible Regrowth from Minoxidil?

Olsen, E. A., Dunlap, F. E., Funicella, T., Koperski, J. A., Swinehart, J. M., Tschen, E. H., & Trancik, R. J. (2002). A randomized clinical trial of 5% topical minoxidil versus 2% topical minoxidil and placebo in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 47(3), 377 385.

First, let’s talk about the event horizon for Minoxidil. With Minoxidil, results can be expected a little faster than Finasteride, so typically shedding is experienced between two and four months, but then re-growth is usually cosmetically perceptible around the one month to six-month mark. This makes sense, as Minoxidil acts more like a stimulant, or growth agonist.

Minoxidil turns more hairs on; it doesn’t necessarily target miniaturization. So Minoxidil doesn’t have as dramatic of an impact on reversing hair miniaturization and thereby improving hair thickness, but it can help to create a denser, fuller head of hair.

For those looking to reverse hair thinning, here are three ways to enhance the effectiveness of minoxidil treatment.

1. Acute Wound Generation via Microneedling

One of the easiest ways to enhance the efficacy of minoxidil is through acute wound generation, which is best administered through microneedling and massage.

Microneedling plus Minoxidil seems to elicit a four-fold greater effect of hair count increases than just Minoxidil alone.

Microneedling elicits growth factors, signaling proteins and enzymatic activity of sulfotransferase. Microneedling may also increase topical absorption and potentially even attenuate scarring – all of which pair well with minoxidil use.

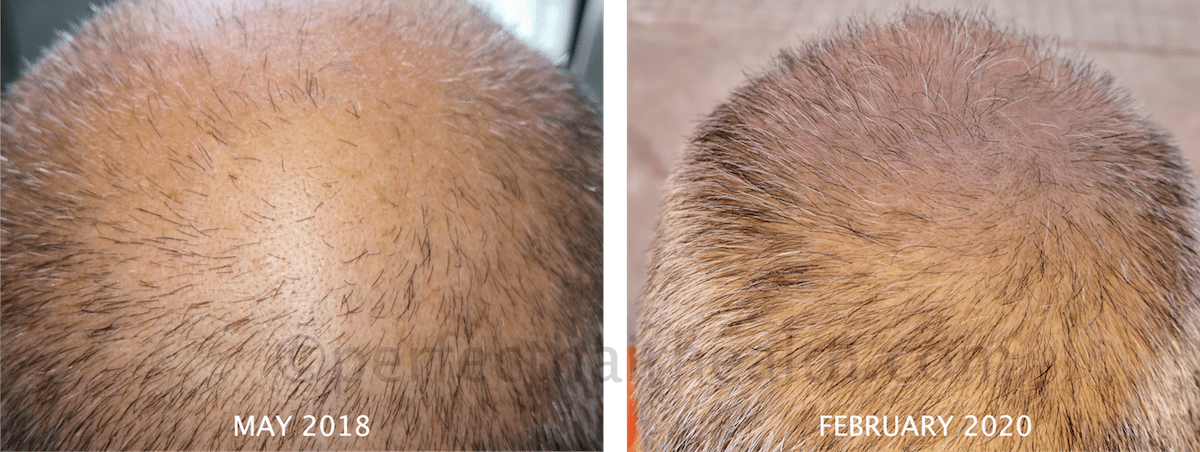

Researchers started testing minoxidil + microneedling as a combination treatment back in 2013 – with incredible results.

One study showed over 12 weeks, minoxidil+ microneedling increased minoxidil efficacy four-fold and led to a 40% increase in hair count – with real, visual hair changes.[1]http://www.ijtrichology.com/article.asp?issn=0974-7753;year=2013;volume=5;issue=1;spage=6;epage=11;aulast=Dhurat

More recently, this study showed that over 6 months, minoxidil + microneedling had a 100% response rate and led to a 25% increase in hair count.[2]https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14764172.2017.1376094?journalCode=ijcl20

It’s suspected that these improvements are due to microneedling’s ability to:

1 – Enhance skin enzymes required to activate minoxidil (i.e., sulfotransferase),

2 – Improve the absorbability of topicals like minoxidil – since the wounding allows for easier access to hair follicles and their blood supply, and

3 – Potentially attenuate or partially reverse fibrosis.

As with microneedling, Perfect Hair Health’s standardized scalp massages may help responders increase hair counts.

2. Switch to higher concentrations

Studies show that minoxidil non-responders see better hair growth after switching to 10% or 15% minoxidil. One such study was conducted on women with female pattern hair loss who were non-responders to 5% Minoxidil. They were trialed with 15% Minoxidil topically, and 70-80% of them saw a significant response. Participants saw an average of about 13% increase in hair counts.[3]https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02486848

So moving from 5% as a non-responder to 15% can really improve results.

Anecdotally, 15% Minoxidil is relatively safe. There’s not a ton of data on it, but when looking at the half-lives of Minoxidil, its transfusion into the system, and how much circulates from topical application, it doesn’t seem like there’s a massive uptake in the systemic volume of Minoxidil from going from 5% to 15%, at least from a biological perspective.

3. Add in topical retinol / retinoic acid

Another way to improve sulfotransferase activity? Using Tretinoin or Retinoic Acid. These are Vitamin A derivatives that help to activate sulfotransferase activity, stimulate a little bit of inflammation and cell turnover and in doing so, make minoxidil way more effective.

Topical minoxidil is delivered as a “pro-drug” – meaning that it is not technically active when it touches the scalp skin. Rather, minoxidil has to come into contact with an enzyme called sulfotransferase.

Unfortunately, many men and women don’t have enough sulfotransferase activity in the skin to elicit a major hair change with minoxidil alone. Fortunately, adding in topical retinol / retinoic acid can increase the activation of sulfotransferase, and thereby minoxidil – potentiating even bigger hair gains.

Just a few short years ago, hair loss sufferers had to ask their doctor to write a prescription for Vitamin A derivatives. There are brands online that sell combination formulas – like Happy Head, Adegen®, and MinoxidilMax. No doctor visit is required.

These companies sell products, but are these companies actually legitimate? Do their products actually contain the advertised ingredients? How do these formulas stand up to our rigorous lab tests? Join the Perfect Hair Health Membership Program to find out.

Summary

About 60% of people seem to be hyper-responders to Minoxidil. They see great hair count increases, and usually, they’ll see this in the first six months of treatment. Then those hair count increases will steadily decline over time. For the other 40% of people who try Minoxidil, there’s zero effect.

For high-responders, there is utility in taking a more multifactorial approach to Minoxidil treatment, where microneedling, high-concentration Minoxidil, and retinoic acid are combined to accelerate hair growth.

References[+]

Stool transplants – also known as fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) – are a controversial therapy reserved for life-threatening bacterial infections and autoimmune disorders. Fascinatingly, people who’ve undergone stool transplants have later reported unintended benefits: weight loss, less acne, personality improvements, and even hair regrowth.

At face value, a connection between stool transplants and hair loss sounds like science fiction. How could altering the bacteria inside of our guts affect hair growth on top of our scalps?

At the same time, new research suggests that the hair loss-fecal microbiota connection is very real, and may even become a future therapeutic target for people looking to regrow hair.

In this article, we’ll dive into the science surrounding stool transplants: what this therapy is, what it does to our gut microbiome, and the evidence linking fecal microbiota transplants to hair regrowth in alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, and maybe even androgenic alopecia.

We’ll even showcase a few before-after photos featured in studies and forums from people who received stool transplants to treat unrelated health conditions, and ended up (accidentally) experiencing hair regrowth.

If you have any questions, feel free to reach us in the comments below.

Table of contents

All-Natural Hair Supplement + Topical

The top natural ingredients for hair growth, all in one serum & supplement.

Take the next step in your hair growth journey with a world-class natural serum & supplement. Ingredients, doses, & concentrations built by science.

What is a fecal microbiota transplant (i.e., stool transplant)?

Our guts are like a storage facility for large colonies of microbes. Because of the role the gut microbiome encompasses, many diseases and conditions that relate to a dysfunctional gut microbiome, have now been treated utilizing a fecal microbiota transplant.

An artist’s rendering of gut organisms and debris

A fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) is basically what it sounds like: the transfer of stool from one individual’s colon into another person. The aim? To improve gut bacteria density and diversity. In other words: increase the total number of “good” bacteria in the gut, as well as the number of “good” species.

Stool transplants – or FMTs – are nothing new. This practice has been around since the 4th century. More recently, it gained notoriety when the FDA approved FMTs for recurrent Clostridium difficile infections – a deadly bacterial infection that often grows resistant to antibiotics [1].

In this context, FMT’s are incredibly successful. For a benchmark, antibiotic treatments for C. difficile tend to boast a 20-30% remission rate. FMTs boast around a 90% remission rate [2]. In the veterinary world, FMT’s are used for similar purposes [3].

While the use of a FMT seems most pertinent to gastrointestinal diseases, there is a much broader spectrum for the therapy in relation to other conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, obesity, and metabolic syndrome (to name only a few) [4, 5].

Can fecal microbiota transplants alter our gut microbiome?

FMTs are perhaps one of the most powerful ways to alter our gut microbiome: the collection of bacteria inside our intestines that help regulate anything from autoimmune reactions to hormonal levels to nutrient metabolism.

C. difficile & stool transplants: alterations to gut flora

In one study, researchers decided to investigate 55 stool samples from donors and recipients who used FMTs as a treatment for C. difficile infections. They found major differences in the pre- versus post-procedure samples of the recipients [6].

Before the procedure, healthy donors’ stools contained a significant portion of the phylum of bacteria – known as Firmicutes and Bacteroides – constituting roughly 85% of bacteria identified.

We can first think of a phylum as the link between different species of bacteria. For example, while an oak tree differs from a palm tree, ultimately, they’re still all trees. As such, no one group can be labeled as good or bad as often the species within those groups can exhibit both helpful and disruptive properties. This is evident with helminth infections – where the same helminth can cause inflammation in the first-world but protect from malaria in the developed world. To put it simply: the effects of a bacteria often rely on its environment, the health of an individual, the ratio of that bacteria to others, and about a billion other factors [7,8].

However, in the case of resistant Clostridium infections, Firmicutes and Bacteroides tend to be absent. This suggests that these phylum may play a role in preventing gut dysbiosis and thereby C. difficile overgrowths.

With respect to the study, here’s what researchers found:

- Prior to the stool transplants, recipients’ stools had lower amounts of Firmicutes and Bacteroides and markedly high Fusobacteria and Proteobacteria.

- Donor stool contained exceptionally higher Firmicutes and Bacteroides, as well as lower Fusobacteria and Proteobacteria.

- After treatments, recipients’ stool showed the higher Firmicutes and Bacteroides as well as lower Fusobacteria and Proteobacteria (thereby more closely resembling that of the donor’s gut).

- After transplantation, the more closely a recipient’s gut matched that of its donor, the more likely that recipient was to experience a remission from C. difficile.

In other words, FMTs significantly altered gut flora – and to the benefit of sick patients.

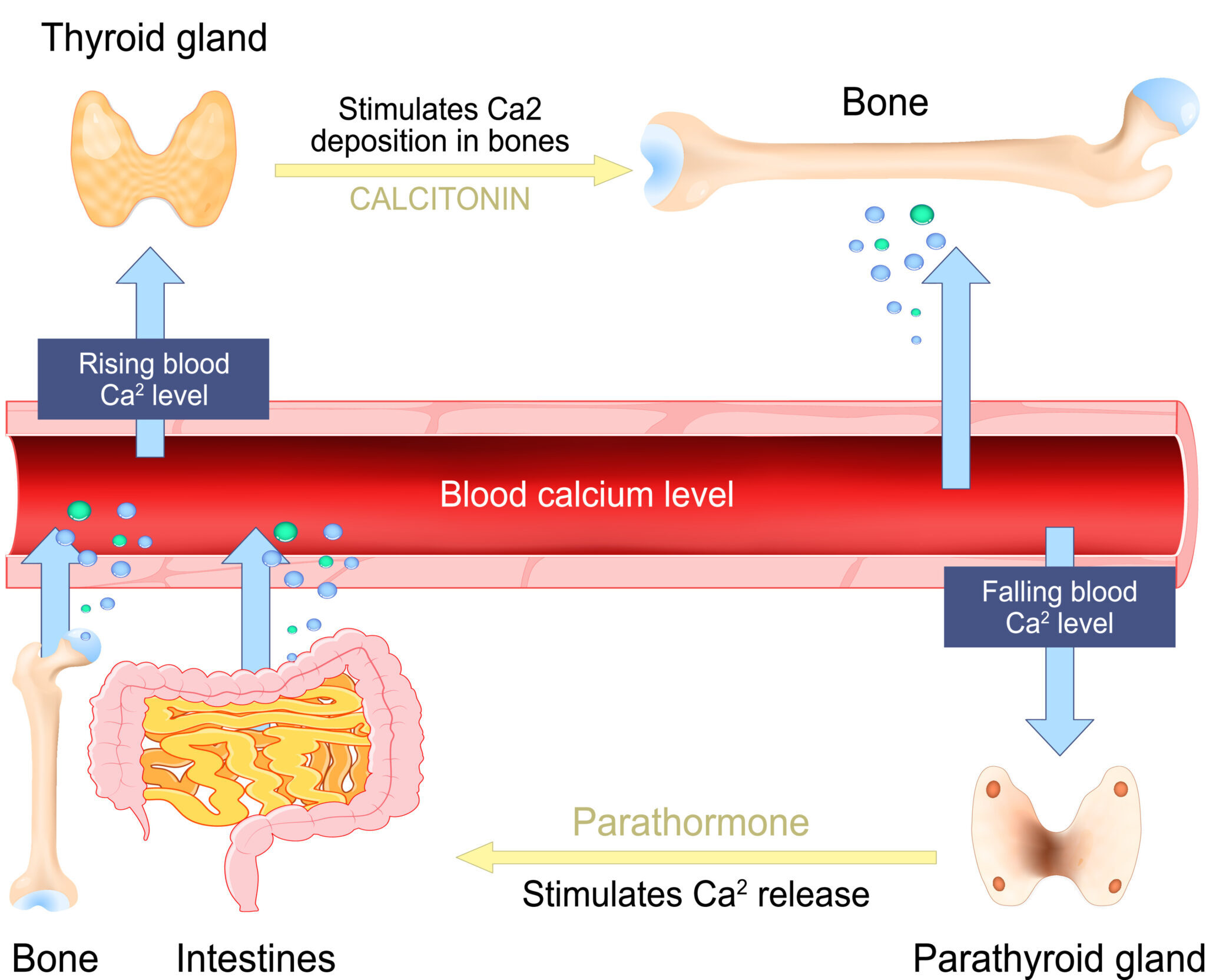

Interestingly, the health of our gut microbiome is linked to many hair loss disorders – particularly alopecia areata and telogen effluvium. Moreover, research now links gut bacteria to the regulation of DHT – the hormone implicated in pattern hair loss.

We’ll dive into this evidence below: what it is, what it means, and why it might rewrite a lot of what we think we know about hair loss.

Stool transplants for hair loss: the evidence

When it comes to FMTs as a treatment for hair loss, evidence is very limited. This is because reports of fecal transplants and hair regrowth have mainly happened by accident – specifically, after a patient with C. difficile + hair loss receives a stool transplant and later inadvertently sees improvements to both conditions.

Nonetheless, there is compelling evidence of a gut microbiome-hair loss connection. To best outline this evidence, we’ll dive into the research on FMT’s and hair loss as organized by :

- Alopecia Areata

- Telogen Effluvium

- Androgenic Alopecia

Let’s begin.

Alopecia areata and fecal microbiota transplants

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune form of hair loss; it often presents as patchy-related hair loss in the scalp. Researchers currently believe AA is the result of a collapse in “immune privilege” of the hair follicles – whereby the immune system begins to read hair follicles as foreign invaders, and then starts to attack them.

Alopecia areata: patchy hair loss

When it comes to stool transplants, alopecia areata is the best-studied form of hair loss. This isn’t saying much – because there’s not a ton of data on stool transplants and hair regrowth in general. Again, the studies here have been unintended and inadvertent: people with alopecia areata seem to have higher rates of gut dysbiosis, and thereby they seem to suffer disproportionately from infections like C. difficile. Therefore, they’re probably more likely to eventually become eligible for extreme treatments like a stool transplant – which is why we have case reports of FMTs and AA-related regrowth in the first place.

So, what limited evidence do we have on stool transplants for hair regrowth from alopecia areata?

Case reports of FMTs and hair regrowth from alopecia areata

Study #1: two uncontrolled retrospective case reports

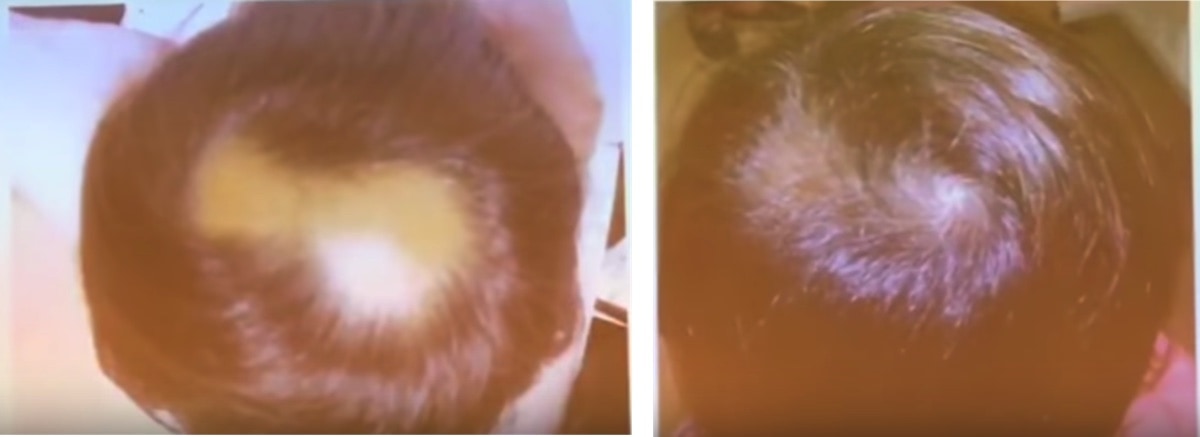

In a study where two patients received an FMT for treating Clostridium difficile, researchers reported that both people saw an unintended benefit of hair regrowth following the procedure [14]. In these cases, both patients were classified as having alopecia universalis – an advanced form of alopecia areata where the hair loss has progresses beyond the scalp and to the body.

In the first case, the 38-year old man began to grow peach fuzz not only on his head, but also his face and arms. The regrowth became cosmetically noticeable 8 weeks after the stool transplant – after having suffered from progressive alopecia universalis for decades without any improvements.

In the second case, a 20-year old man – diagnosed with alopecia universalis 2 years prior to his FMT – saw major improvements to scalp hair regrowth over a 1.5-year period after receiving a stool transplant. Prior to the FMT, this subject had tried to treat his alopecia using corticosteroid injections, topical steroids, squaric acid, and laser treatments— all to no avail. While this man also received steroid injections within his scalp after the FMT, he began to grow hair throughout the rest of his body as well, even where had not received a steroid injection [21].

Study #2: a case report of FMT + hair regrowth in an elderly patient with diffuse alopecia areata

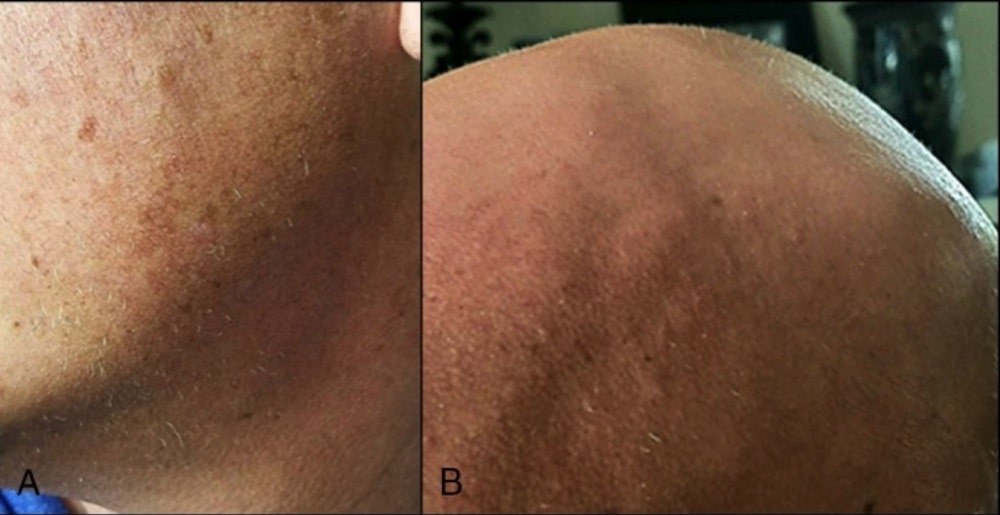

In a second study investigating FMT’s effects on an elderly man (86-year old) with diffuse alopecia areata, researchers found some unexpected benefits [15]. Originally, FMT was used to treat his intestinal disorders (with success). However, alongside the treatment of his other digestive ailments, his hair thickness began to return. What’s more, his previously gray hair had regrown as its original color.

These are just three case reports. That’s not really “overwhelming” evidence…

You’re right! We always have to evaluate any intervention in respect to its quality and quantity of evidence. In regard to FMT and alopecia areata, the quality and quantity of evidence is low: three uncontrolled, retrospective case reports.

Having said that, we also have to recognize that the total number of alopecia areata patients who (1) develop C. difficile, and (2) have it progress to the severity where they become eligible for an FMT – is also low. On that note, the evidence here has excited other research teams enough to launch a clinical trial on FMT and alopecia areata – the results of which will (hopefully) be available in the coming year.

So, needless to say, the preliminary evidence (and mechanistic data) supporting a connection between is FMT and AA-related regrowth is exciting enough to continue exploring.

How might FMT’s improve alopecia areata?

Alopecia areata is mainly categorized by an autoimmune attack on the hair follicles. This is predominantly mediated by a group of immune cell known as T-cells. Specifically, a type of T-cell known as TH17 [16].

Not surprisingly, TH17 is a major contributor to intestinal conditions that manifest as inflammation. Since the gut is our largest site of immune cell concentration, then by altering the gut microbiome to a more favorable anti-inflammatory profile, we may be able to alter T-cell activity throughout the rest of our body.

In fact, studies have shown that modulating the microbiome to favor this anti-inflammatory profile can nearly shutdown TH17 cell activity [17]. By this very same mechanism, it is possible that a more widespread shutdown of TH17 could alleviate a TH17-mediated attack on hair follicles – even at the top of the scalp.

Furthermore, there is an established link between inflammatory bowel disease and alopecia areata [18]. The implication: an unhealthy microbiome may drive both inflammatory bowel disease and alopecia areata. After all, patients with alopecia areata and inflammatory bowel conditions who undergo FMT seem to inadvertently regrow hair – and at a consistency worth noting by investigators.

Summary so far: Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune form of hair loss; it’s likely driven by the over-activation of T-cells, and specifically, TH17 cells. Interestingly, patients with AA who’ve undergone stool transplants (FMTs) to treat C. difficile infections have inadvertently regrown hair. The gut microbiome is the body’s largest site of immune cell concentration – and thereby TH17 activation. So, it’s plausible that FMTs might dampen TH17 immune activation – all by restoring gut microflora balance to a more commensal state.

Telogen effluvium and stool transplants

Telogen effluvium (TE) is a temporary form of hair loss that is characterized by a dysregulation of the hair cycle.

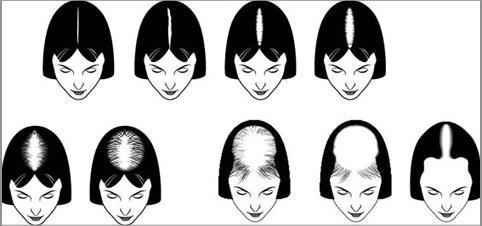

This can occur in many ways: for instance, too many hairs can “shed” prematurely, or there can be a delay between when a hair sheds out and when a new hair grows in (to start a new hair cycle). This often presents as diffuse thinning, or sometimes even region-specific shedding (oftentimes the hairline for women).

A hair loss patient with suspected telogen effluvium (TE)

What causes telogen effluvium (TE)?

Telogen effluvium (TE) is sort of like a catch-all diagnosis for a wide array of hair loss triggers. But the main drivers of TE are often considered (1) stress (emotional or physical), (2) nutrient imbalances, and (3) chronic conditions (i.e., hypothyroidism, heavy metal toxicities, etc.).

Currently, there are no studies investigating a link between FMTs and TE. However, there is mechanistic evidence that FMTs may help address some (of the many) underlying factors leading to TE.

For example, nutrient deficiencies – namely, iron, zinc, and/or vitamin D – have been associated with telogen effluvium [20]. Given that evidence implicates the state of the microbiome in nutrient absorption, it’s possible that disruptions to the microbiome may result in poor nutrient absorption and, consequently, telogen effluvium-related hair shedding [21].

Research has also found elevated cadmium levels in some people with TE – a trace element that may trigger hair shedding if consumed in excness [22]. Most interesting, though, is that excessive cadmium has also been shown to alter the gut microbiome of mice in a way that directly mirrors individuals plagued by antibiotic-resistant Clostridium difficile infections… the exact condition FMT is designed to treat [23].

Altogether, direct (i.e., by bacterial infection) or indirect (i.e., by excess cadmium) changes to the microbiome, both of which seem to be associated with telogen effluivum, may benefit from FMT.

Summary so far: Telogen effluvium (TE) is a temporary form of hair loss caused by a disruption to the hair cycle – oftentimes resulting from stress, nutrient imbalances, or a chronic condition. While no evidence directly implicates stool transplants as a therapeutic procedure for TE, there is mechanistic data showing that our gut microbiome has the capacity to improve chronic conditions as well as the synthesis of vitamins commonly found as deficient in TE patients. Therefore, it’s possible that stool transplants might help TE by addressing its underlying causes. But again, we’re extrapolating here!

Androgenic alopecia and fecal transplants

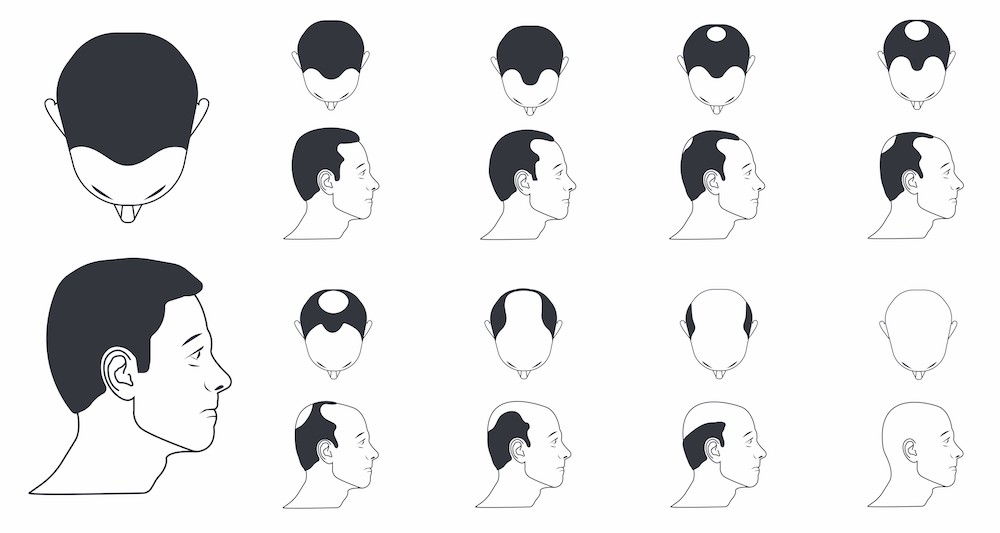

Androgenic alopecia (AGA) is one of the world’s most common hair loss disorders – affecting at least 50% of women and 80% of men throughout a lifetime. Its often characterized by progressive hair follicle miniaturization, whereby affected hair follicles get thinner and thinner over a series of hair cycles. It presents most commonly across the top of the scalp as temple recession + a bald spot in men, and diffuse thinning in most women.

Androgenic alopecia in a male: temple recession

What causes androgenic alopecia (AGA)?

While all of the causes aren’t fully elucidated, most researchers agree that AGA is caused by a combination of male hormones and genetics, and possibly the scalp’s environment (i.e., inflammatory microorganisms, the contraction of muscles surrounding the scalp perimeter, inflammation-mediated tension, etc.).

Specifically, the hormone dihydrotestosterone (DHT) seems to overexpress in balding scalp regions. In vitro studies demonstrate that DHT may trigger premature shedding, inflammatory signaling proteins, and cell death in dermal papillae cells (the “powerhouse” of the hair follicle) – all of which can lead to progressive hair follicle miniaturization. Moreover, studies have shown that men without DHT do not go bald, and that reducing DHT can help prevent (and partially reverse) the balding process.

Is there evidence that stool transplants can improve pattern hair loss (AGA)?

Clinical evidence? No. Mechanistic evidence? Yes. Anecdotes of AGA improvements after stool transplants? Yes – even with photos. We’ll uncover all of this below.