- About

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Education.

Prioritize knowledge. Make better choices.

- Evidence.

Sort good studies from the bad.

- Regrowth.

Get bigger hair gains.

Team MembersPhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Rob English

Founder, researcher, & consumer advocate

- Research Team

Our team of PhD’s, researchers, & more

Editorial PolicyDiscover how we conduct our research.

ContactHave questions? Contact us.

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- — Jenna, 31, U.S.A.

I have attached my before and afters of my progress since joining this group...

- — Tom, 30, U.K.

I’m convinced I’ve recovered to probably the hairline I had 3 years ago. Super stoked…

- — Rabih, 30’s, U.S.A.

My friends actually told me, “Your hairline improved. Your hair looks thicker...

- — RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A.

I also feel my hair has a different texture to it now…

- — Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA

Firstly thank you for your work in this field. I am immensely grateful that...

- — Ben M., U.S.A

I just wanted to thank you for all your research, for introducing me to this method...

- — Raul, 50, Spain

To be honest I am having fun with all this and I still don’t know how much...

- — Lisa, 52, U.S.

I see a massive amount of regrowth that is all less than about 8 cm long...

Client Testimonials150+ member experiences.

Scroll Down

Popular Treatments- Treatments

Popular treatments. But do they work?

- Finasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Dutasteride

- Oral

- Topical

- Mesotherapy

- Minoxidil

- Oral

- Topical

- Ketoconazole

- Shampoo

- Topical

- Low-Level Laser Therapy

- Therapy

- Microneedling

- Therapy

- Platelet-Rich Plasma Therapy (PRP)

- Therapy

- Scalp Massages

- Therapy

More

IngredientsTop-selling ingredients, quantified.

- Saw Palmetto

- Redensyl

- Melatonin

- Caffeine

- Biotin

- Rosemary Oil

- Lilac Stem Cells

- Hydrolyzed Wheat Protein

- Sodium Lauryl Sulfate

More

ProductsThe truth about hair loss "best sellers".

- Minoxidil Tablets

Xyon Health

- Finasteride

Strut Health

- Hair Growth Supplements

Happy Head

- REVITA Tablets for Hair Growth Support

DS Laboratories

- FoliGROWTH Ultimate Hair Neutraceutical

Advanced Trichology

- Enhance Hair Density Serum

Fully Vital

- Topical Finasteride and Minoxidil

Xyon Health

- HairOmega Foaming Hair Growth Serum

DrFormulas

- Bio-Cleansing Shampoo

Revivogen MD

more

Key MetricsStandardized rubrics to evaluate all treatments.

- Evidence Quality

Is this treatment well studied?

- Regrowth Potential

How much regrowth can you expect?

- Long-Term Viability

Is this treatment safe & sustainable?

Free Research- Free Resources

Apps, tools, guides, freebies, & more.

- Free CalculatorTopical Finasteride Calculator

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: What Causes Hair Loss?

- Free ResourceFree Guide: Standardized Scalp Massages

- Free Course7-Day Hair Loss Email Course

- Free DatabaseIngredients Database

- Free Interactive GuideInteractive Guide: Hair Loss Disorders

- Free DatabaseTreatment Guides

- Free Lab TestsProduct Lab Tests: Purity & Potency

- Free Video & Write-upEvidence Quality Masterclass

- Free Interactive GuideDermatology Appointment Guide

More

Articles100+ free articles.

-

Oral Minoxidil – Ultimate Guide

-

Introducing Ulo: The Future of Hair Loss Telemedicine

-

OS-01 Hair Review: Does It Live Up to the Hype?

-

Stretching The Truth: 3 Misrepresented Claims From Hair Loss Studies

-

Minoxidil Shedding – What to Expect & When it Stops

-

Does Minoxidil Cause Skin Aging?

-

Thermus Thermophilus Extract Does Not Increase Hair Density By 96.88%, Despite Dermatology Times’ Claims.

-

Does Retinoic Acid (Tretinoin) Improve Hair Growth From Minoxidil?

PublicationsOur team’s peer-reviewed studies.

- Microneedling and Its Use in Hair Loss Disorders: A Systematic Review

- Use of Botulinum Toxin for Androgenic Alopecia: A Systematic Review

- Conflicting Reports Regarding the Histopathological Features of Androgenic Alopecia

- Self-Assessments of Standardized Scalp Massages for Androgenic Alopecia: Survey Results

- A Hypothetical Pathogenesis Model For Androgenic Alopecia:Clarifying The Dihydrotestosterone Paradox And Rate-Limiting Recovery Factors

Menu- AboutAbout

- Mission Statement

Education. Evidence. Regrowth.

- Team Members

PhD's, resarchers, & consumer advocates.

- Editorial Policy

Discover how we conduct our research.

- Contact

Have questions? Contact us.

- Before-Afters

Before-Afters- Transformation Photos

Our library of before-after photos.

- Client Testimonials

Read the experiences of members

Before-Afters/ Client Testimonials- Popular Treatments

-

ArticlesRegrowth from Minoxidil: How Much Should I Expect?

First Published Feb 24 2023Last Updated Oct 29 2024Pharmaceutical Researched & Written By:Perfect Hair Health Team

Researched & Written By:Perfect Hair Health Team Reviewed By:Rob English, Medical Editor

Reviewed By:Rob English, Medical Editor

Want help with your hair regrowth journey?

Get personalized support, product recommendations, video calls, and more from our researchers, trichologists, and PhD's dedicated to getting you the best possible outcomes.

Learn MoreArticle Summary

How much regrowth can we expect from minoxidil? As with any hair loss treatment, it depends on a number of factors: genetic variance in the SULT1A1 gene, the delivery method of minoxidil (oral vs. topical), the dosing amount and schedule, and if minoxidil is combined with interventions that might enhance its hair growth-promoting effects, such as retinoic acid and/or microneedling. For non-responders to minoxidil, you can use these factors to understand why minoxidil might not be working for you, and in doing so, create workarounds to make the drug more effective. This article discusses the science behind minoxidil-induced hair growth, and explains ways to make minoxidil work – even if your first attempt at using the drug is unsuccessful.

Full Article

Topical minoxidil is an FDA-approved treatment for male and female pattern hair loss, also known as androgenic alopecia (AGA).

Despite its popularity, not very many people continue using topical minoxidil for the long-run. In fact, one clinical study found that by the one-year mark, 95% of topical minoxidil users voluntarily quit applying the drug – with more than 2/3rds of them citing “low effect” as their rationale.[1]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17917938/

So, what sort of hair regrowth can we expect from minoxidil? Why do so many people quit using the topical? And what can we do to maximize minoxidil’s hair growth-promoting effects, and in doing so, set ourselves up for sustainable hair regrowth years into the future?

What Is Minoxidil?

Topical minoxidil is the only medication approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenic alopecia (AGA) in both males and females. Since its use as an anti-hypertensive drug in 1979, researchers have long-noted a nearly universal “adverse event” in oral minoxidil users: unexpected new hair growth along the limbs, chest, face, and scalp.[2]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7030707/

This led to to the reformulation of minoxidil as a topical, and subsequent clinical trials to test its efficacy on treating AGA. In 1988 and 1992, 5% and 2% minoxidil became commercial available as an over-the-counter hair growth treatment for men and women, respectively.

How Does Minoxidil Work?

Researchers aren’t totally sure how minoxidil regrows hair.

Having said that, they suspect that minoxidil may work through at least one (or all) of the following mechanisms:

- Opening potassium ion channels – which increases blood, oxygen, and nutrient transport to balding regions (i.e., increased microcirculation)

- Modulation of prostaglandin analogues (i.e., decreased inflammation)

- Anti-androgenic activity in hair follicle sites (i.e., decreased dihydrotestosterone (DHT) – the hormone causally linked to baldness).

How Much Regrowth Should We Expect From Minoxidil?

Technically speaking, “hair regrowth” isn’t a term specific enough to be meaningful. Are we talking about changes to total hair counts? Changes to hair thicknesses? Increases to terminal hairs? Vellus hairs? Hair density changes? Over what time period: 1 month, 3 months, 5 years? What about the percentage of people who notice increased hair growth versus those who don’t?

Depending on how we define “hair regrowth”, our answers will vary wildly.

For these reasons, our team prefers to use more specific language surrounding hair regrowth. Here are the two metrics we tend to consider most important when evaluating the efficacy of a hair loss treatment option:

- Response Rate. This term can be defined through a question: “Of the people who try this intervention, what percent will see a slowing, stopping, or partial reversal of their hair growth versus a placebo group – and over a reasonable time period?”

- Regrowth Rate. This term’s definition varies depending on the quality of data on an intervention. But in general, it’s the change in an objective hair growth endpoint that closely mirrors the perception of “visual improvements” to hair. For instance, this might be the change in terminal hair counts, hair density (i.e., the ∆ in hair counts x the ∆ in hair thickness), or hair weight (i.e., the difference in the weight of hair shaved off before/after a study was conducted, controlling for hair growth timing).

What Is Minoxidil’s Response Rate?

Despite being an FDA-approved hair growth drug, topical minoxidil’s response rate is as low as 40-60%.[3]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25112173/

This is because topical minoxidil is applied to the scalp as a pro-drug – meaning that it’s inactive. It needs to come into contact with a skin enzyme called sulfotransferase – which is produced by the SULT1A1 gene – in order to active in the skin, and then attach to hair follicles where it can elicit its hair growth-promoting effects.

Unfortunately, upwards of 60% of men and women do not have high enough levels of sulfotransferase in their skin to elicit a response to topical minoxidil.[4]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24283387/

This means that for (potentially) a majority of people who try topical minoxidil, it won’t lead to any hair growth, because not enough of it will activate within the scalp to create an effect on hair growth.

Fortunately, there are ways to enhance minoxidil’s efficacy – and the activity levels of sulfotransferase in the scalp skin. We’ll get into these later in the article.

What Is Minoxidil’s Regrowth Rate?

This depends on a number of factors, including someone’s:

- Gender

- Severity of hair loss

- Genetic variance in the SULT1A1 gene

- The delivery method of minoxidil (oral vs. topical)

- The dosing amount and schedule

- If minoxidil is combined with interventions that might enhance its hair growth-promoting effects (more on this later).

Having said that, if we narrow our definition of Regrowth Rate to changes to “hair weight” occurring over a 1+ year usage period, and we narrow our patient population to healthy men and women who are facing androgenic alopecia, we can use clinical data to set ballpark expectations.

A well-designed study by Price et al. (1999) sought to determine the effect of 2% and 5% topical minoxidil on cumulative hair weight changes throughout 96 weeks of treatment. Compared to the placebo and untreated groups, hair weight changes from 2% and 5% topical minoxidil were 20% and 30% higher for 2% and 5% topical minoxidil users at the 52-week mark, respectively.[5]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10534633/

Here’s a chart summarizing the details (Note: participants withdrew from treatment at the vertical line denoted at week 96):

Price VH, Menefee E, Strauss PC. Changes in hair weight and hair count in men with androgenetic alopecia, after application of 5% and 2% topical minoxidil, placebo, or no treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999 Nov;41(5 Pt 1):717-21. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70006-x. PMID: 10534633.

So, despite that 40-60% of topical minoxidil users don’t respond to treatment, after averaging out all participants’ hair growth results, most studies on topical minoxidil show that overall hair growth results are statistically improved.

This is the big problem with topical minoxidil: its hair growth outcomes are bifurcated.

On the one hand, we have 40-60% of users seeing zero effect from the drug. On the other hand, we have 40-60% of users seeing big amounts of hair growth. These bifurcated results can average a 20-30% cumulative hair weight change at the one-year mark.

Key Takeaway: despite ~50% of people not responding to 2% or 5% topical minoxidil, most studies show statistically significant improvements to hair counts. This is because a subset of participants are often hyper-responders to minoxidil, which bring up the average hair counts for everyone.

Do Minoxidil’s Results Last Long-Term?

Unfortunately, hair regrowth from topical minoxidil is not necessarily as long-lasting as most would hope.

This is because clinical studies also show that, over time, the efficacy of topical minoxidil wanes – meaning that its hair growth-promoting effects diminish over a number of years, even despite keeping users above the placebo group. [6]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12196747/[7]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2180995/

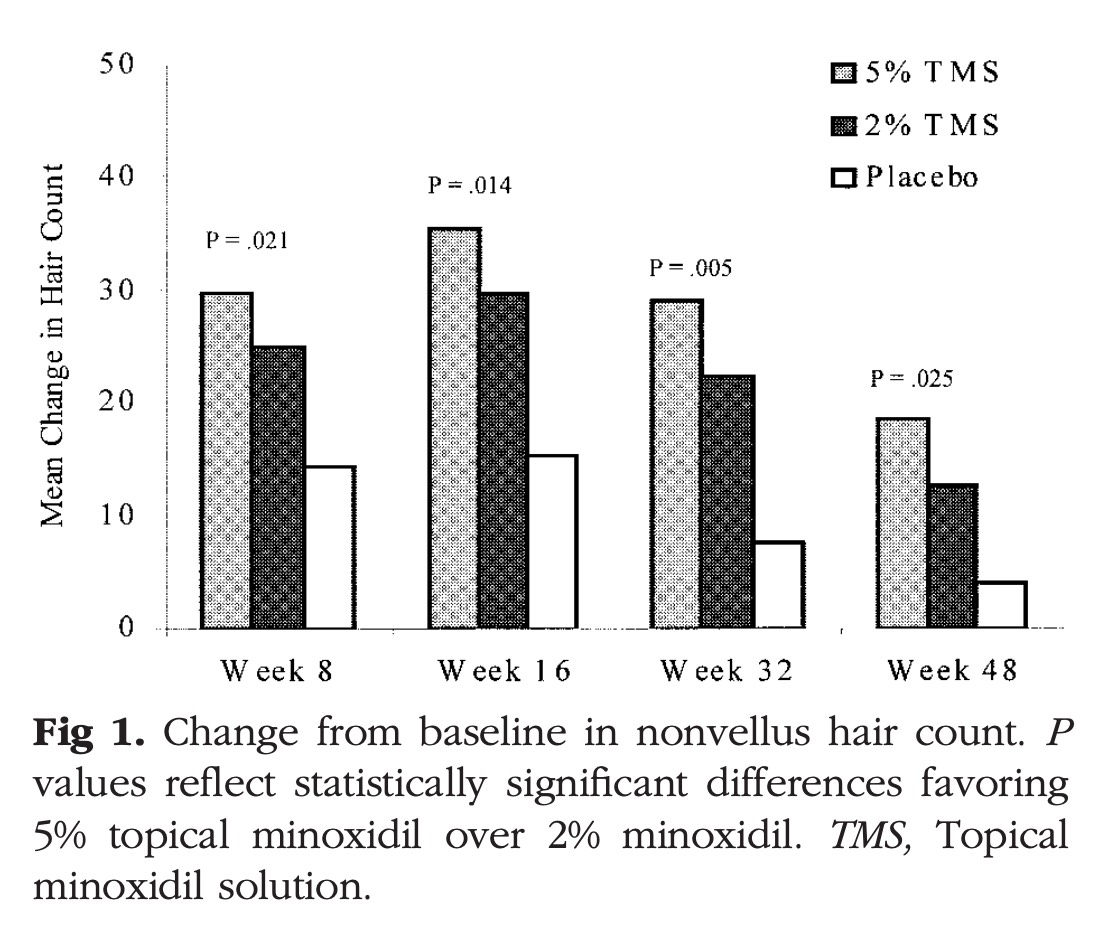

This was already evident in the above study, which showed a trend downward for cumulative changes to hair weights from weeks 52 to 96. And these results are consistent across other studies. Just see the diminishing regrowth results from this 48-week study on 2% and 5% topical minoxidil versus placebo:[8]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12196747/

Olsen, E. A., Dunlap, F. E., Funicella, T., Koperski, J. A., Swinehart, J. M., Tschen, E. H., & Trancik, R. J. (2002). A randomized clinical trial of 5% topical minoxidil versus 2% topical minoxidil and placebo in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 47(3), 377–385.

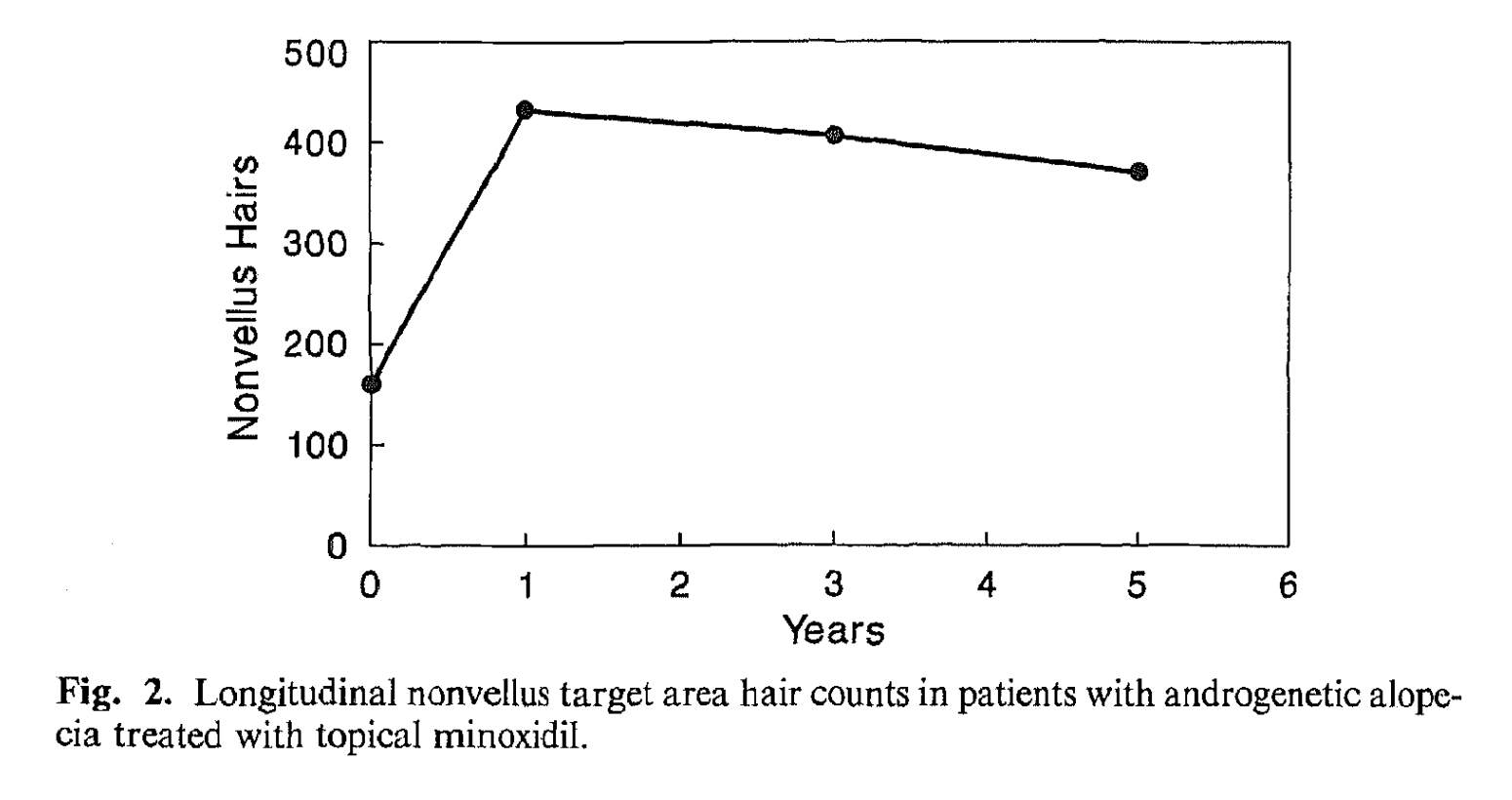

Moreover, here’s a five-year study tracking topical minoxidil’s efficacy, which seems to wane after year one:[9]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2180995/

Olsen, E. A., Weiner, M. S., Amara, I. A., & DeLong, E. R. (1990). Five-year follow-up of men with androgenetic alopecia treated with topical minoxidil. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 22(4), 643–646.

For more information on these topics, see this article: Minoxidil: How Long Do Results Last (Even After Quitting)?

Factors Affecting Topical Minoxidil’s Ability To Grow Hair

To summarize from the above, topical minoxidil has a response rate of just 40-60%. This is because a large number of users lack enough skin activity of an enzyme known as sulfotransferase – which is used to turn minoxidil into minoxidil sulfate, where the drug can then become active, attach to hair follicle sites, and have a positive impact on hair parameters.

But even with these poor response rates, 2% to 5% topical minoxidil still can improve hair weights by 20-30% over a 52-week period – and lead to modest hair count improvements – a portion of which will lead to cosmetically significant improvements to hair.

This is because the 40-60% of people who do respond to topical minoxidil tend to respond relatively robustly.

Factors affecting minoxidil’s response rates and regrowth rates are person-specific, and depend on (at least) the following:

- The person. Age, gender, hair loss severity, and genetic variations in the SULT1A1 gene

- The drug. Delivery methods (i.e., topical versus oral), along with dosing amounts and schedules (i.e., 5% twice-daily)

- Minoxidil enhancers. Whether minoxidil is used alongside therapies that enhance skin penetration and/or sulfotransferase activity (i.e., retinoic acid and/or microneedling)

This begs the question: if we’re worried we may not respond to minoxidil, how can we enhance the drug’s efficacy?

Fortunately, there are a number of ways to take someone from a non-responder to a great responder.

How Can Minoxidil Results Be Improved?

There are a handful of strategies to improve the effectiveness of minoxidil. If you’re looking for a deep-dive into the science, this article is a great resource.

Otherwise, here are the highlights:

- Increase the dilution of topical minoxidil to 15%. Clinical studies show that suspected non-responders to 2% and 5% minoxidil tend to see robust hair regrowth at higher dilutions ranging from 10% to 15% minoxidil.

- Add in minoxidil enhancers. Retinoic acid (i.e., tretinoin) and microneedling both help increase dermal penetration of minoxidil and active more sulfotransferase.

- Switch to oral minoxidil. Unlike topical minoxidil – which gets sulfated in the skin – oral minoxidil goes through processing in the liver whereby most people have an abundance of sulfotransferase to activate the drug. This leads to dramatically higher response rates – with daily doses of 2.5 mg and higher sometimes promoting 90% response rates in clinical trials.

Many people inside our membership community have used these strategies above to move from minoxidil non-responders to minoxidil hyper-responders. We hope they help you, too.

We hope these recommendations help take your hair growth results to a new level.

References[+]

References ↑1 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17917938/ ↑2 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7030707/ ↑3 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25112173/ ↑4 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24283387/ ↑5 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10534633/ ↑6, ↑8 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12196747/ ↑7, ↑9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2180995/ Want help with your hair regrowth journey?

Get personalized support, product recommendations, video calls, and more from our researchers, trichologists, and PhD's dedicated to getting you the best possible outcomes.

Learn More

Perfect Hair Health Team

"... Can’t thank @Rob (PHH) and @sanderson17 enough for allowing me to understand a bit what was going on with me and why all these [things were] happening ... "

— RDB, 35, New York, U.S.A."... There is a lot improvement that I am seeing and my scalp feel alive nowadays... Thanks everyone. "

— Aayush, 20’s, Boston, MA"... I can say that my hair volume/thickness is about 30% more than it was when I first started."

— Douglas, 50’s, Montréal, CanadaWant help with your hair regrowth journey?

Get personalized support, product recommendations, video calls, and more from our researchers, trichologists, and PhD's dedicated to getting you the best possible outcomes.

Join Now - Mission Statement

Scroll Down

Scroll Down